The Making of a Legend

Here's what you need to know about young Winston Churchill: he was terrible at school. Not "charmingly mediocre"—genuinely bad. He failed the Sandhurst entrance exam twice. His father, Lord Randolph Churchill, wrote him off as a disappointment.

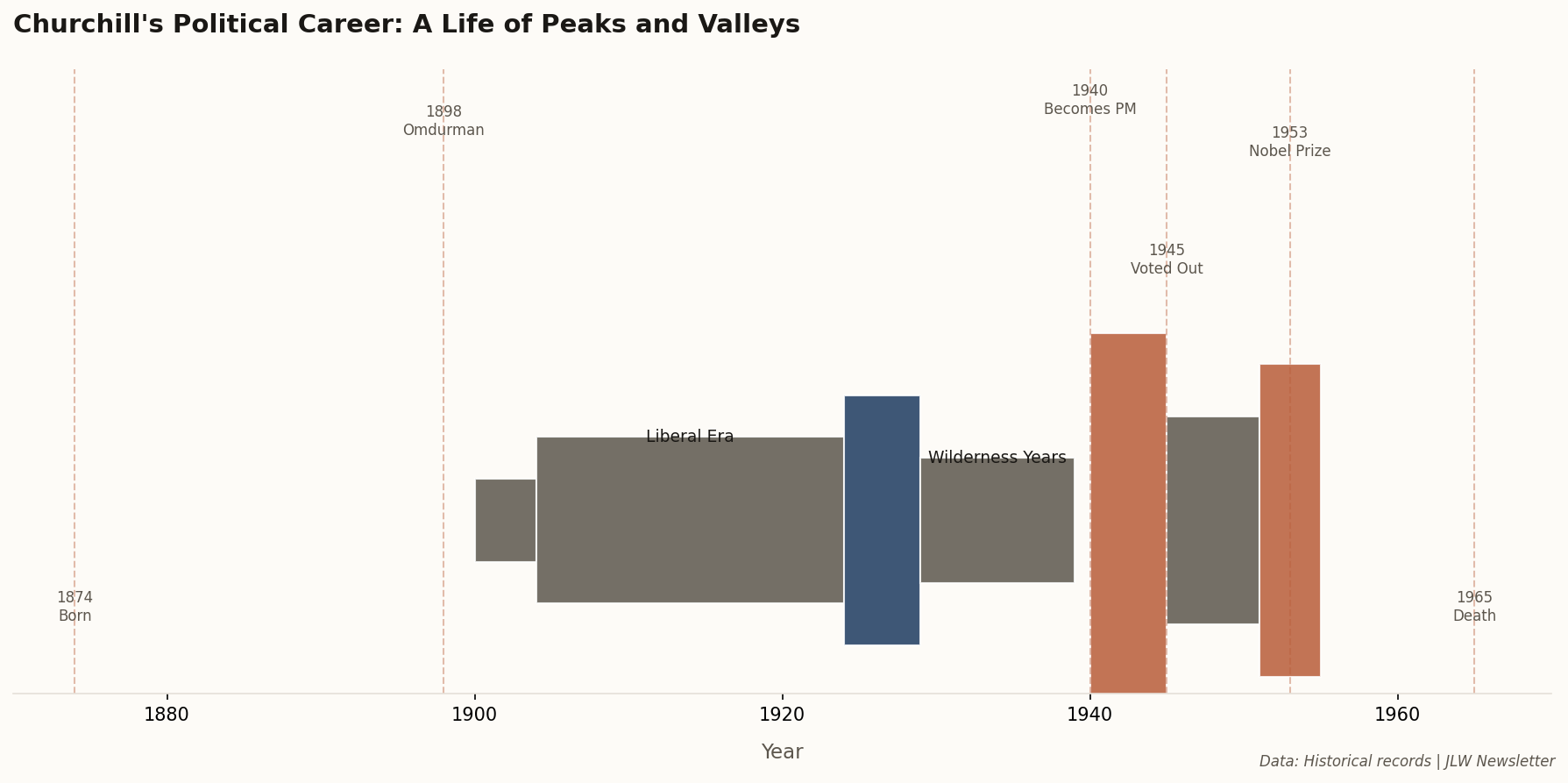

And yet. Born at Blenheim Palace on November 30, 1874, Churchill responded to academic failure by becoming, essentially, his own university. Stationed in India with the 4th Queen's Own Hussars, a bored 22-year-old devoured Plato, Gibbon, Darwin, and Macaulay—giving himself the education Harrow and Sandhurst never provided. He also played polo obsessively, even with a chronically dislocated shoulder.

The adventures came fast. In 1898, he participated in the Battle of Omdurman—the last major British cavalry charge in history. In 1899, captured during the Boer War, he escaped from a POW camp in Pretoria and traveled 300 miles through enemy territory to safety in Portuguese East Africa. The escape made him a national celebrity overnight.

"I am all for the public schools but I do not want to go there one moment longer than is necessary."

— Winston Churchill, on his unhappy schooldays at Harrow

By age 25, he was an MP. By 30, he had defected from the Conservatives to the Liberals—a move that earned him a reputation as an opportunistic turncoat that would shadow him for decades. The pattern was set: Churchill would always be brilliant, always be controversial, and never be trusted by his own side.