The Numbers That Break Your Brain

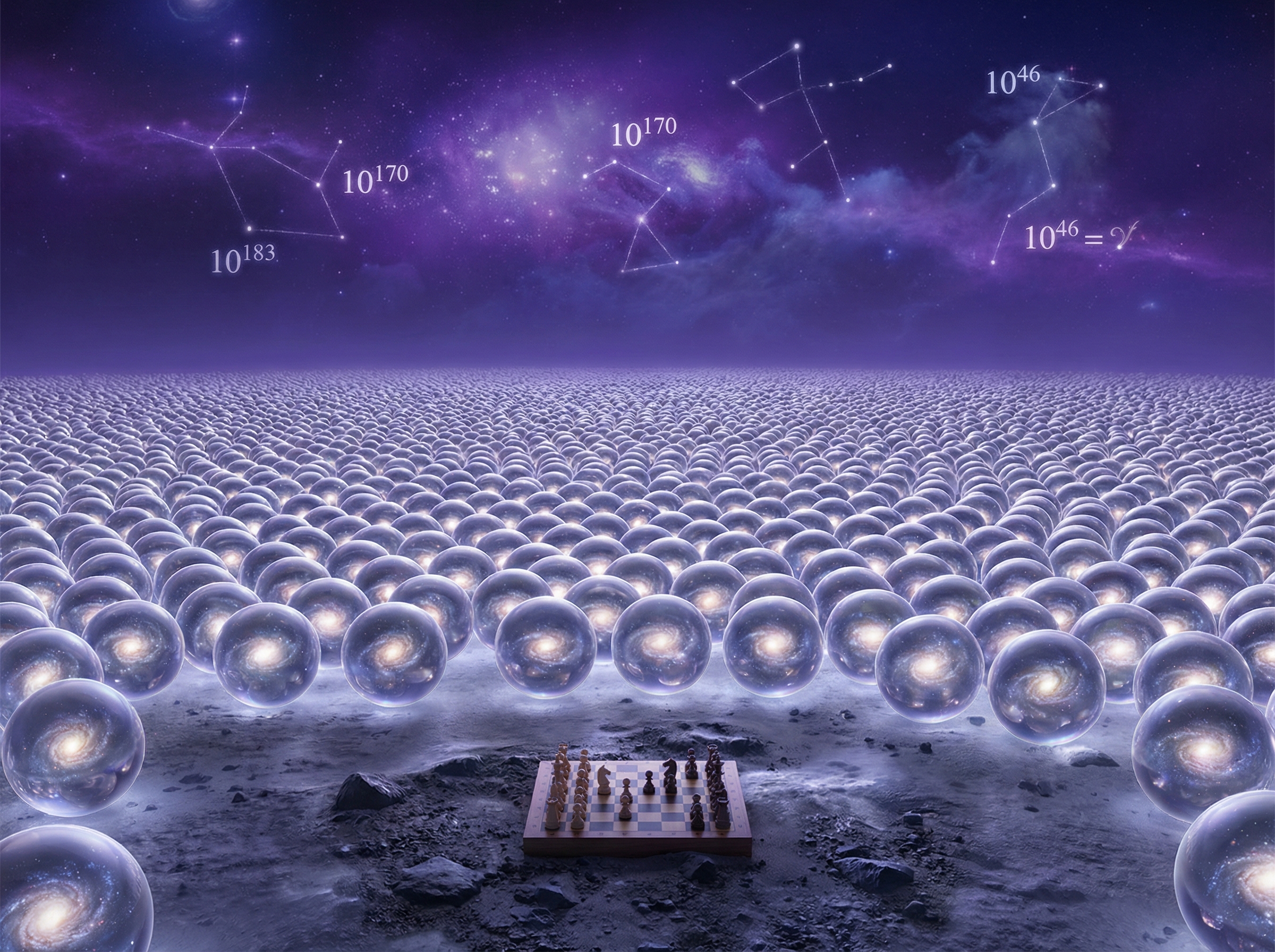

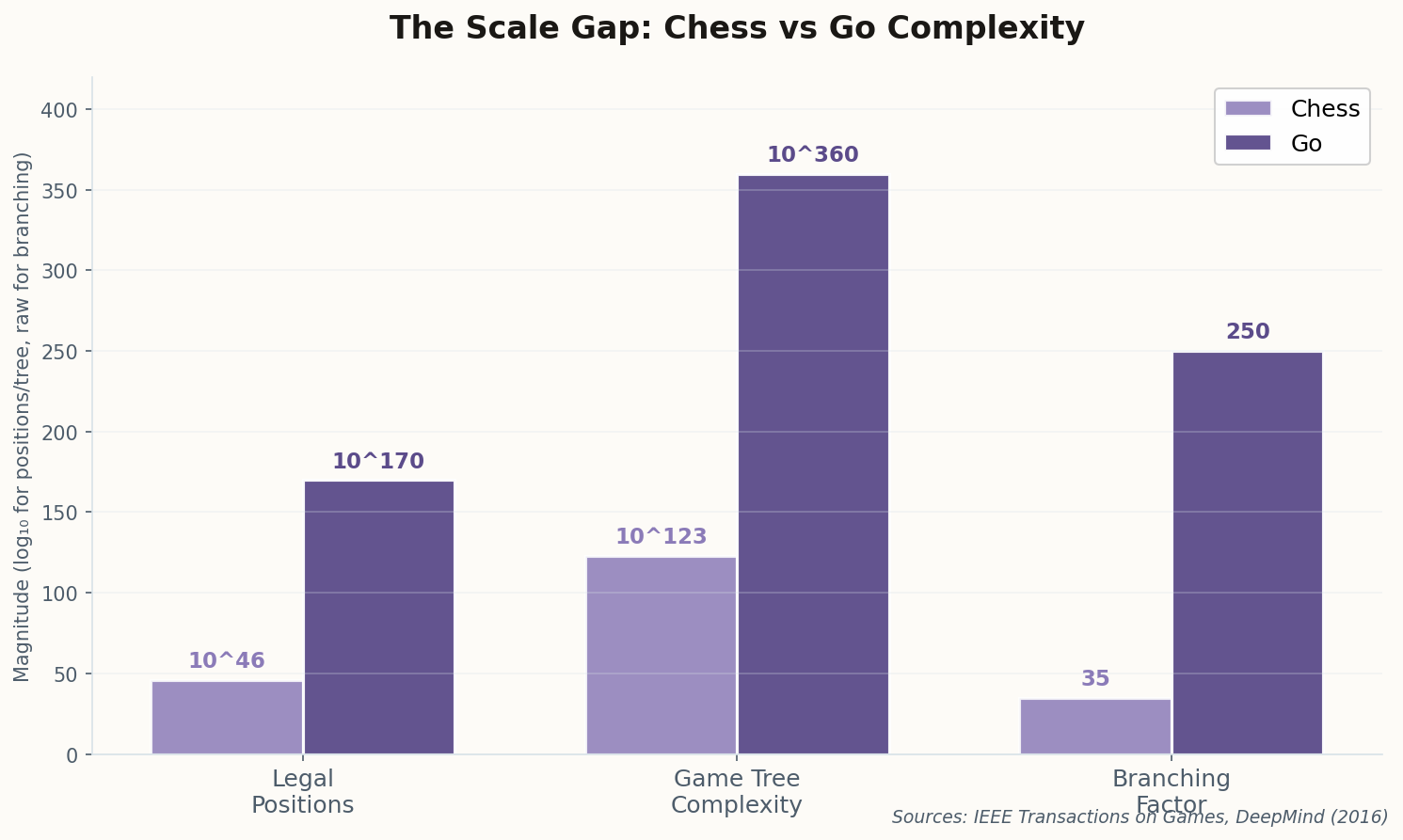

Let's start with the math, because the math is absurd. Chess has roughly 1046 legal positions. That's a lot. It's more than the number of grains of sand on Earth. Go has 10170. That's not "more." That's a different universe of more. The number of legal Go positions exceeds the number of atoms in the observable universe—and then keeps going for another hundred orders of magnitude.

The branching factor tells the same story from a different angle. In any given chess position, you have about 35 legal moves to consider. In Go, you have about 250. And the game tree complexity—the total number of possible games from start to finish—is 10123 for chess versus 10360 for Go. DeepMind's David Silver put it memorably: "The search space in Go is vast... a number greater than the number of atoms in the universe."

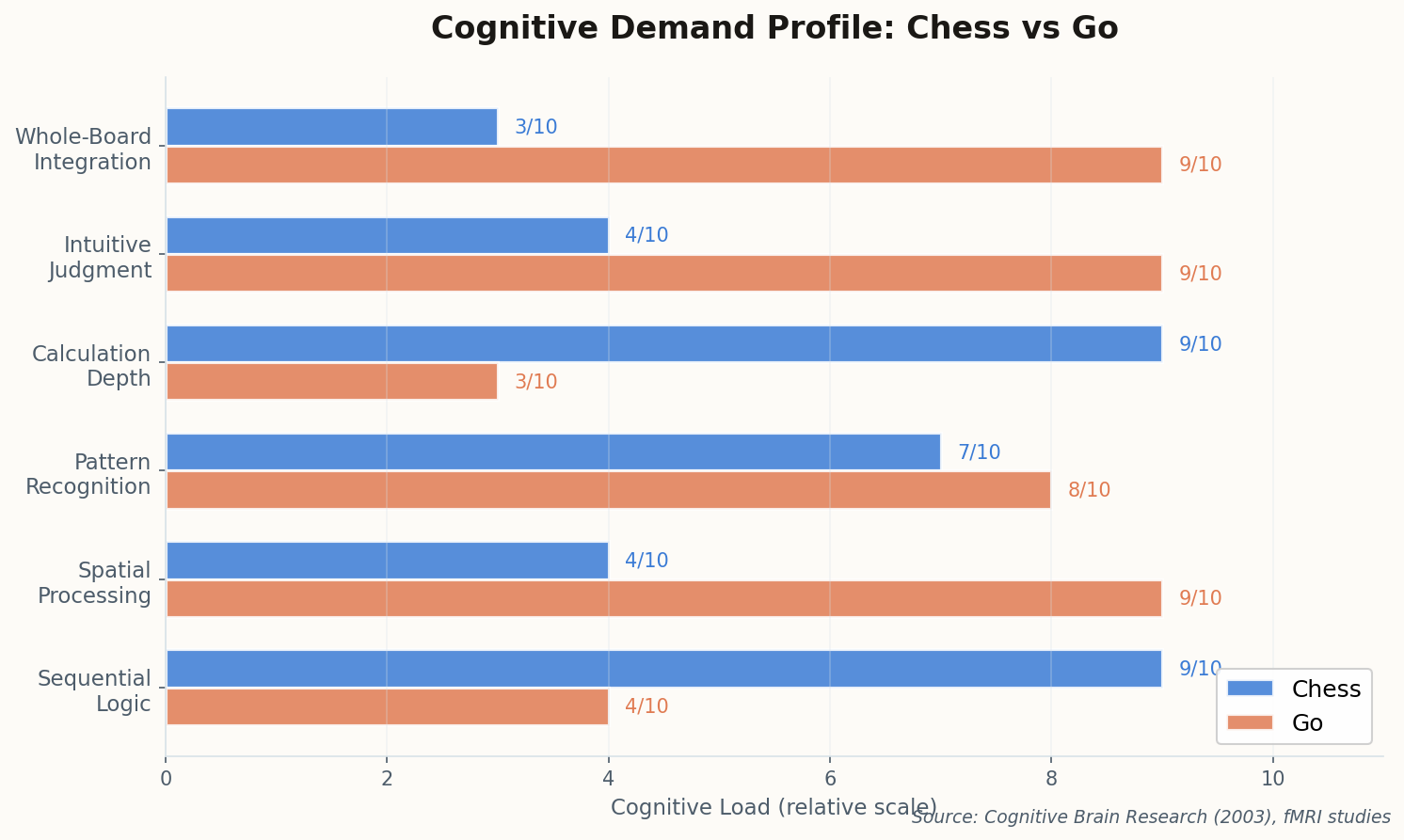

But here's the critical judgment call: raw complexity doesn't automatically mean "harder for humans." Our brains don't brute-force search. We use heuristics, pattern recognition, and intuition. The question isn't how many positions exist—it's what kind of thinking each game demands. And that's where the story gets genuinely interesting.