The Paranoia That Built a Fortress

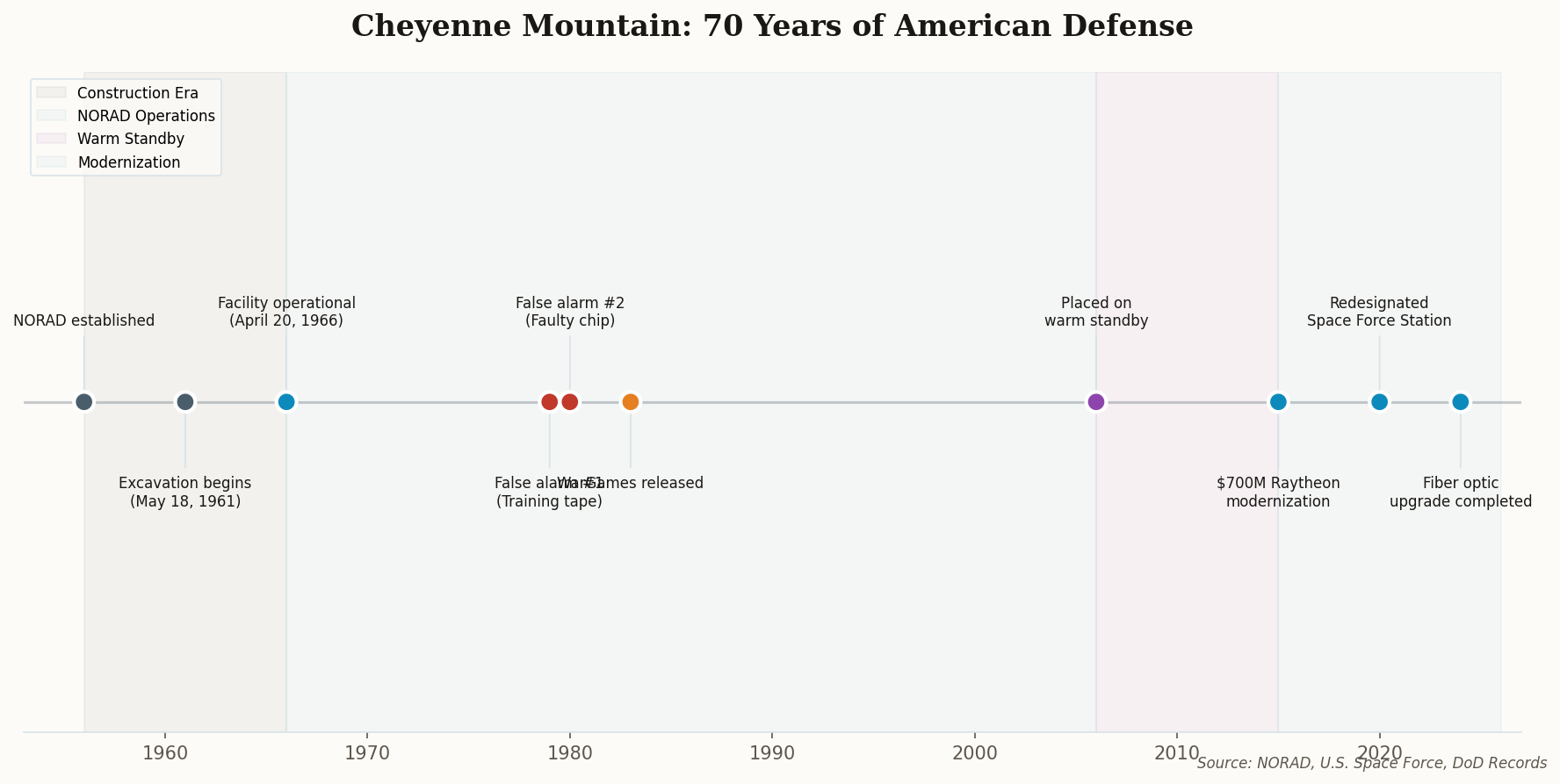

In 1956, the men running NORAD had a problem that no amount of radar stations could solve. The Soviet Union was building intercontinental ballistic missiles, and every above-ground command center in North America had just become a target. The interim headquarters at Ent Air Force Base in Colorado Springs was a glorified office building. A single warhead would erase it — and with it, the entire nerve center of continental air defense.

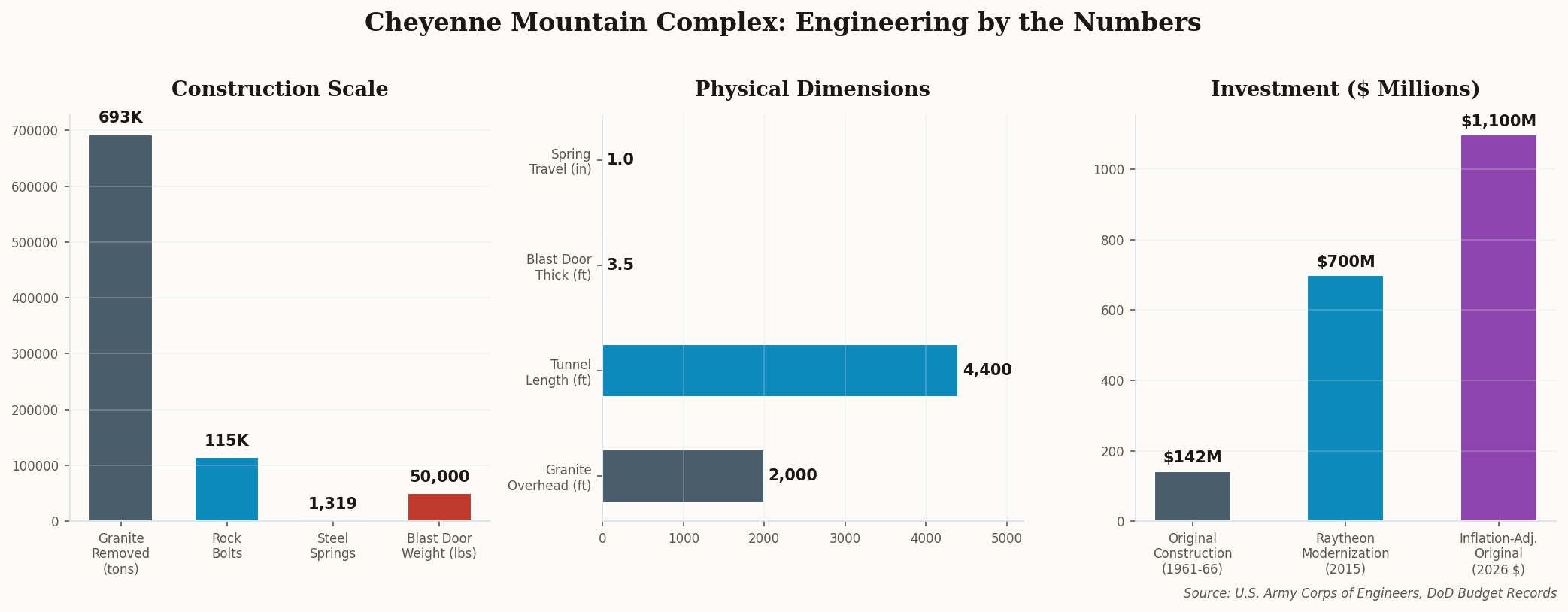

The solution was as audacious as it was straightforward: dig a hole in a mountain and put the command center inside it. On May 18, 1961, construction crews began blasting into Cheyenne Mountain, a granite massif on the Front Range of the Rockies. Over the next five years, they would remove 693,000 tons of rock — enough to fill a freight train stretching from Colorado Springs to Denver — and spend $142.4 million (roughly $1.3 billion in today's dollars) building what remains the most heavily fortified military installation on Earth.

The facility went operational on April 20, 1966. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and prime contractor Utah Mining and Construction had created something unprecedented: a small city inside a mountain, designed to absorb a direct nuclear strike and keep functioning. It wasn't a bunker. It was a statement — that even in the worst case, someone would still be watching.