3,000 Feet of Fiber Through Solid Granite

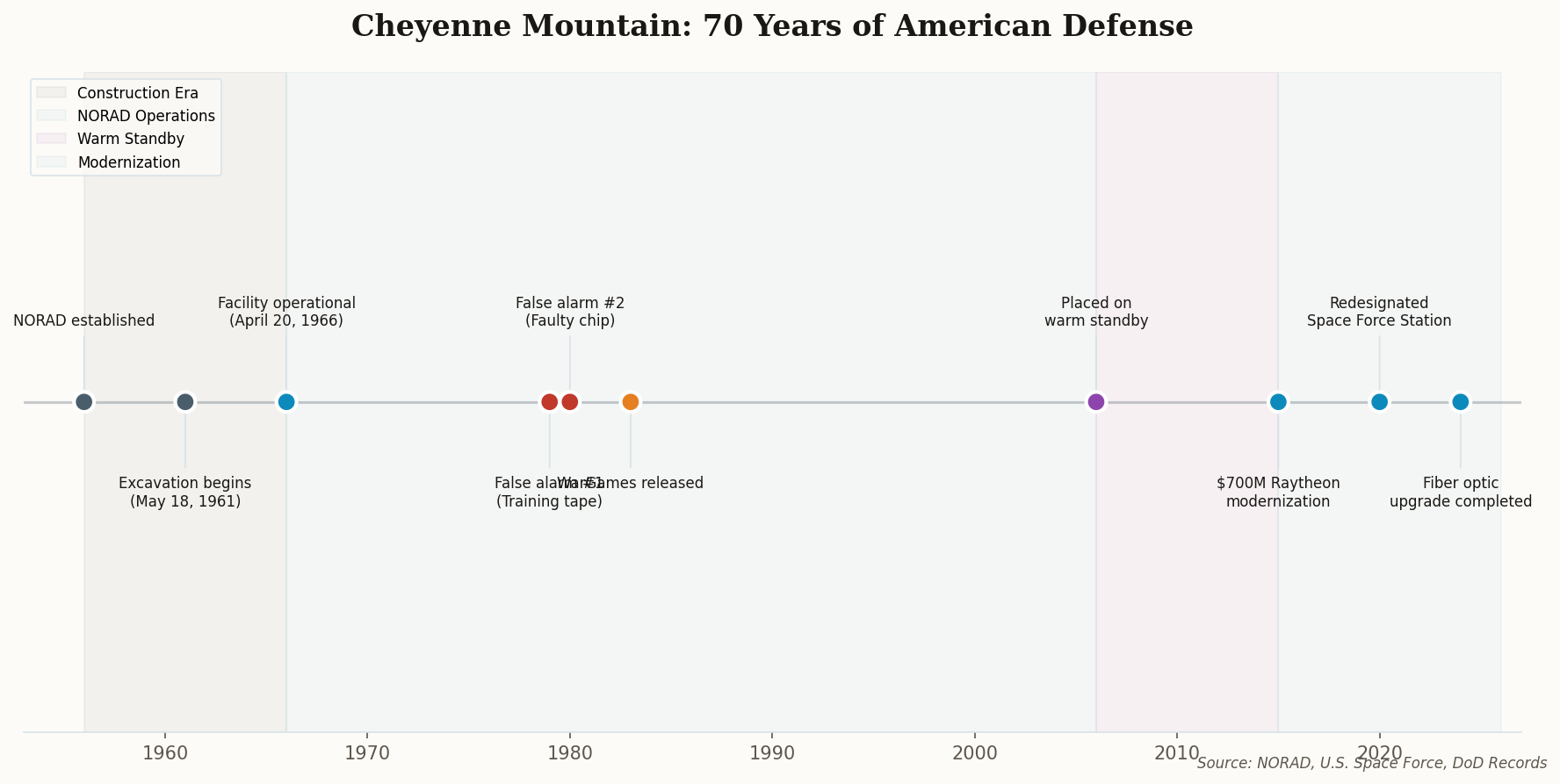

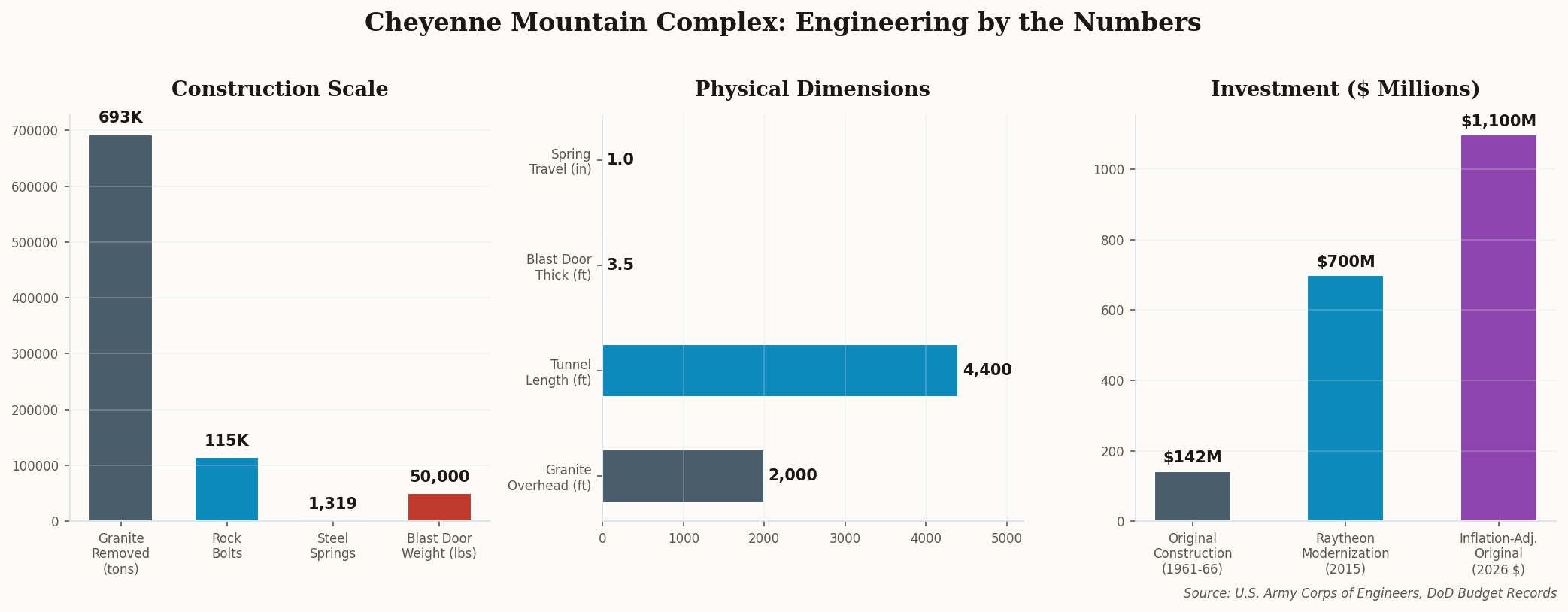

In July 2024, the 210th Engineering Installation Squadron completed what might be the most unusual fiber optic installation in history: threading over 3,000 feet of secondary fiber cable through tunnels blasted out of granite in the 1960s. The project wasn't routine maintenance. It was a deliberate bet that the facility once left to gather dust would need bandwidth to match anything the Pentagon operates above ground.

The installation gives Cheyenne Mountain Space Force Station redundant, high-speed data connectivity essential for processing real-time missile warning data. Think about what that means: the same mountain that tracked Soviet bombers on cathode-ray tubes in 1966 now handles satellite telemetry and space domain awareness data at fiber-optic speed. The infrastructure is 60 years old. The data flowing through it measures in milliseconds.

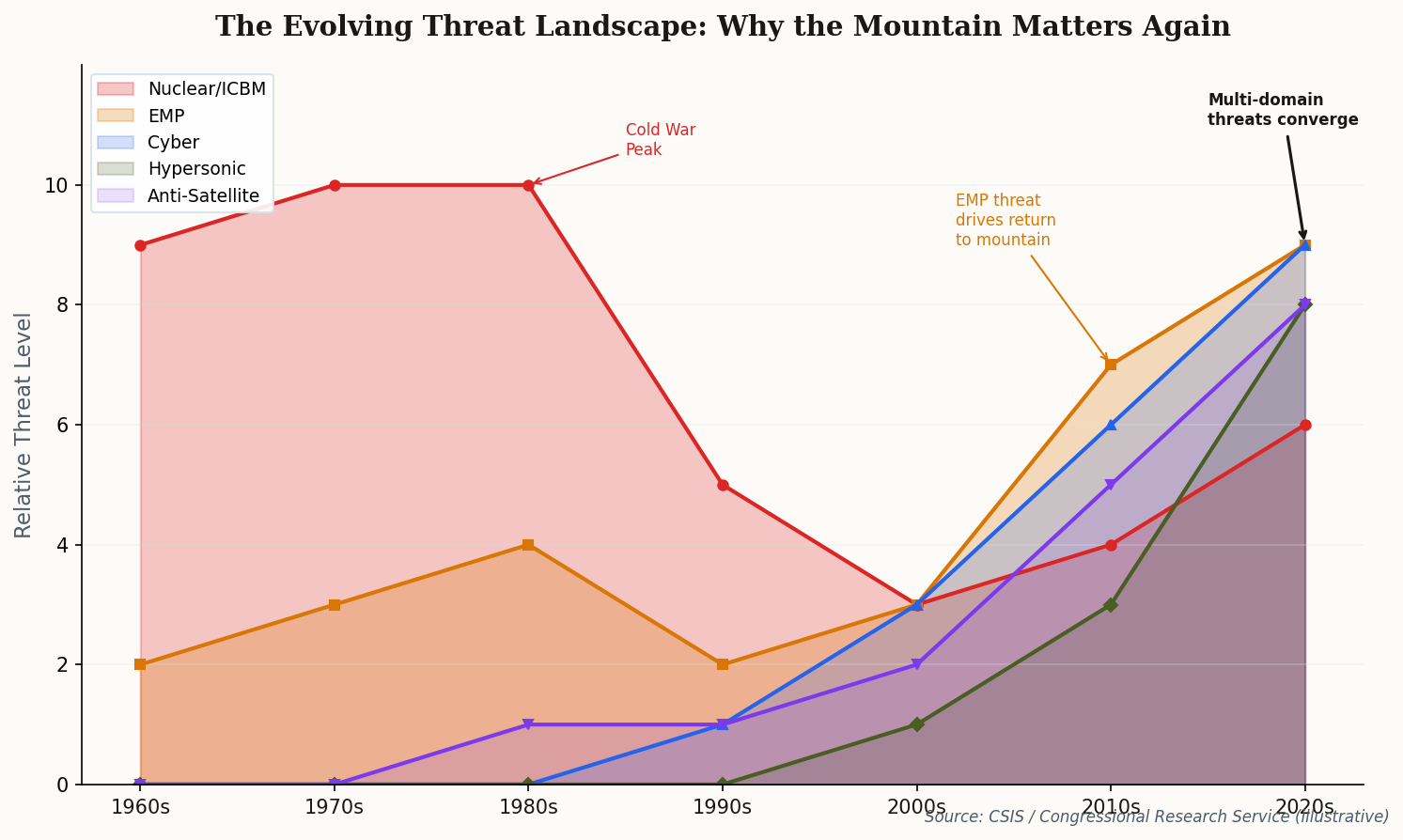

The facility now falls under Space Base Delta 1, reflecting a shift that would have baffled its Cold War architects. NORAD's granite fortress is now, officially, a Space Force installation. The rebranding isn't cosmetic—it tracks the reality that the threats the mountain was built to detect have migrated from bombers to orbits.