The Army Just Gave Every Squad a Bomber. It Costs Less Than a Rifle Scope.

At Fort Stewart, Georgia, soldiers from the 3rd Infantry Division's 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team just finished running what may be the most consequential training exercise in a generation. During Spartan Focus drills on February 2, operators from the 6th Squadron, 8th Cavalry Regiment flew C100 reconnaissance drones reconfigured as bombers—dropping 3D-printed training munitions on simulated enemy positions.

That sentence deserves a second read. The Army is teaching cavalry scouts to fly kamikaze quadcopters with printed warheads. The C100 is a medium-range recon platform repurposed as close air support for the infantry squad. Not the brigade. Not the battalion. The squad.

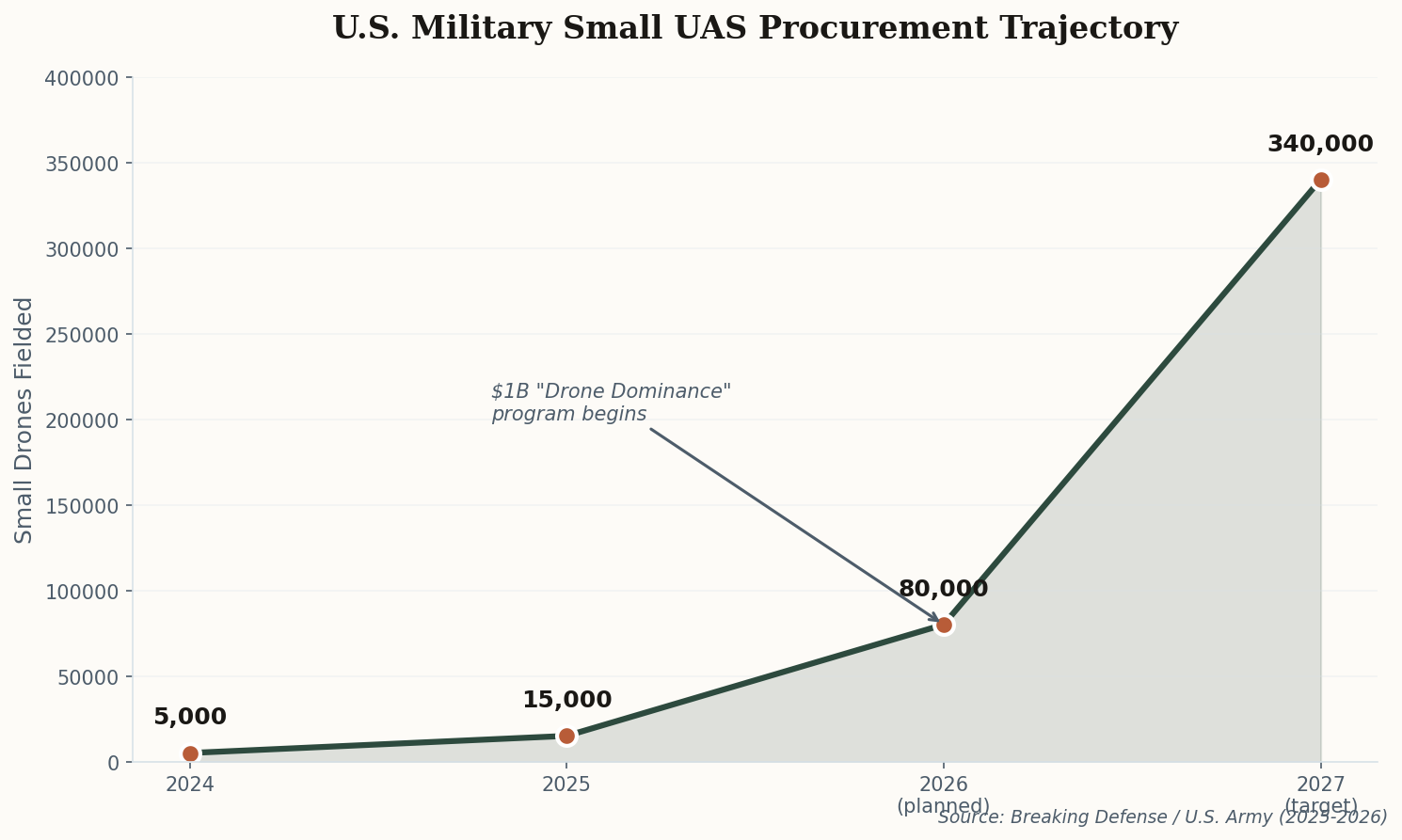

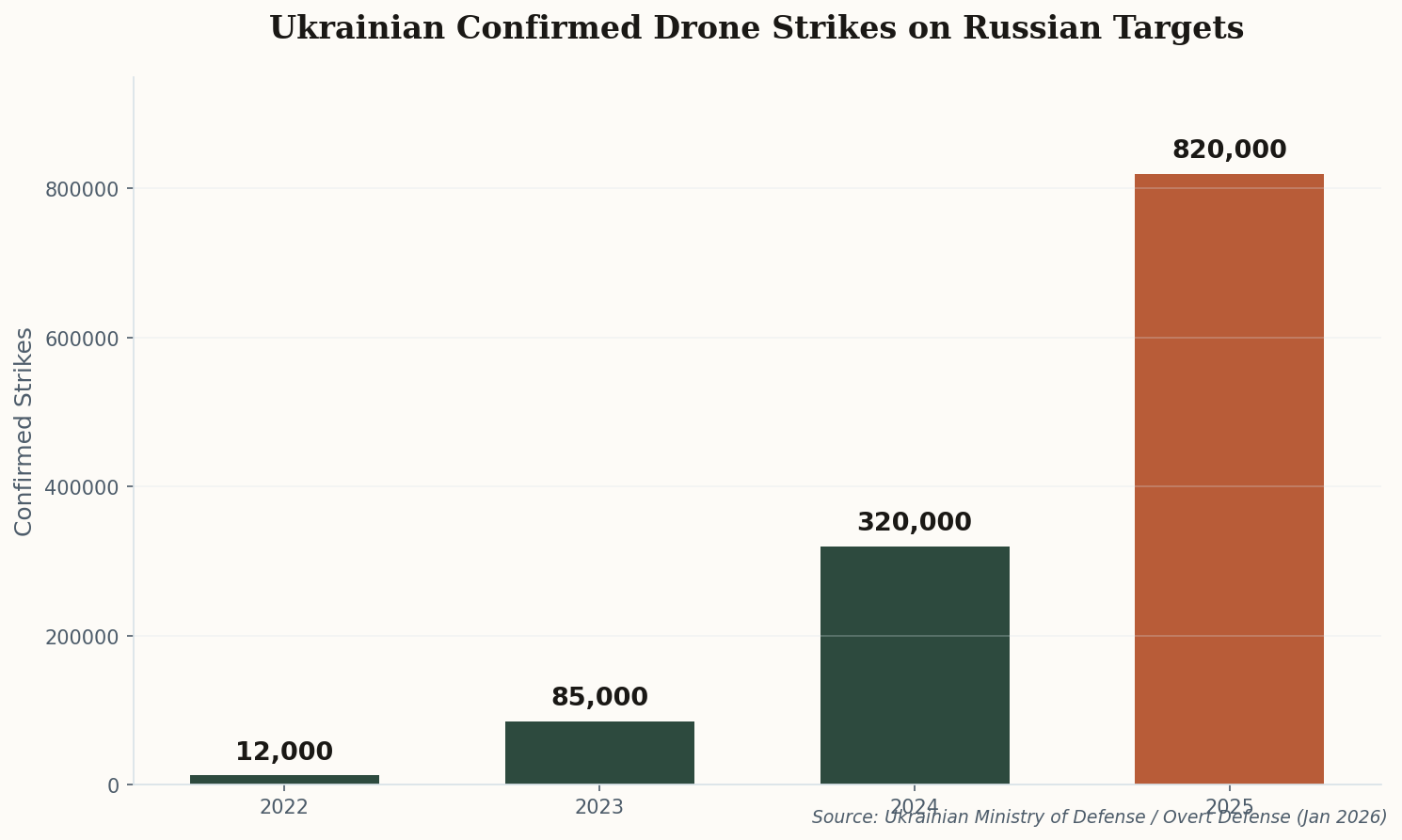

This is Ukraine's lesson, internalized. When War Secretary Pete Hegseth ordered every Army squad to carry expendable drones by October 2026, it sounded like aspirational PowerPoint. Fort Stewart just showed it's real. The exercise focused on integration—how a drone operator coordinates with supported infantry on target ID, release procedures, and deconfliction. The mundane choreography that separates a useful tool from friendly fire.

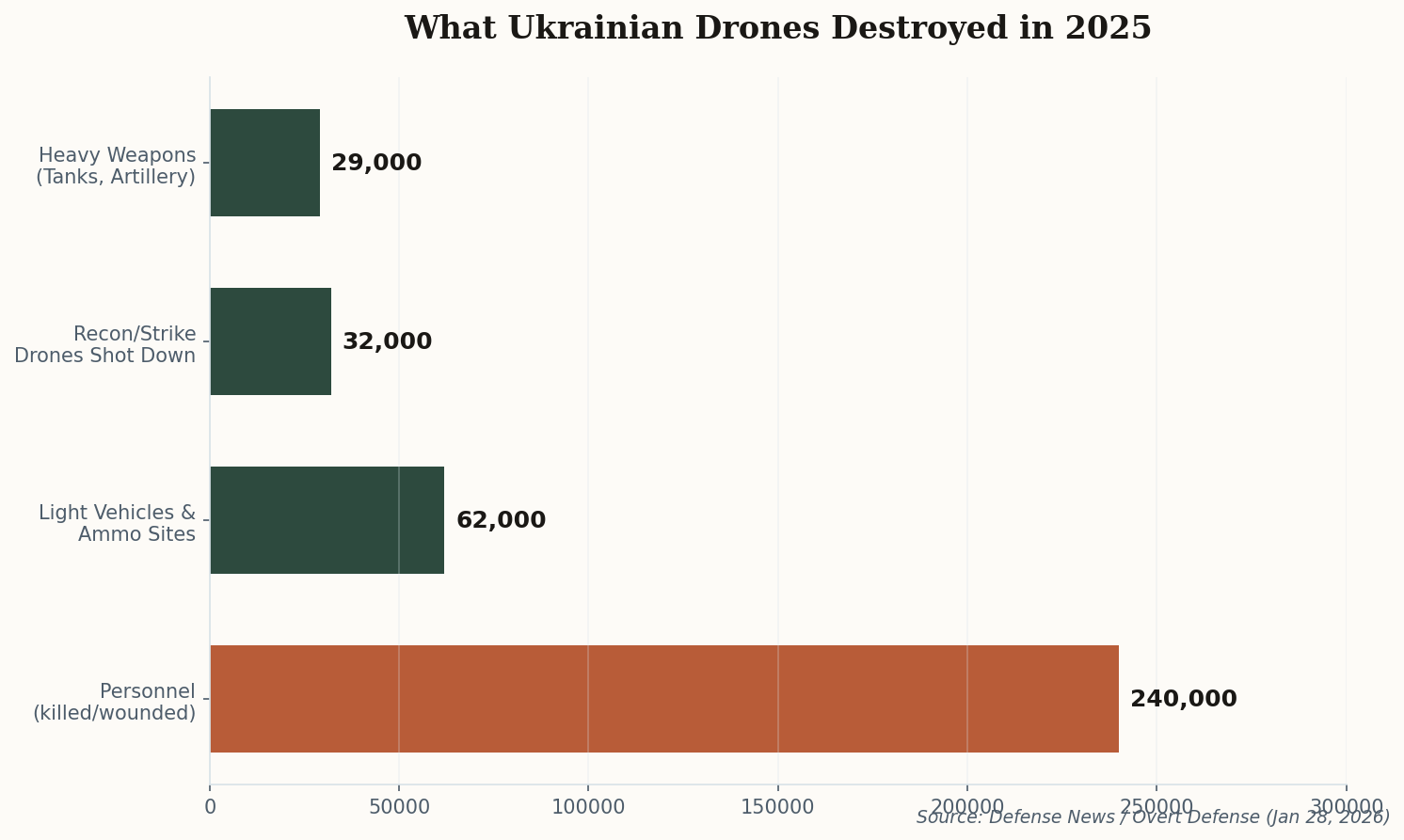

The implications run deeper than tactics. When a $4,000 drone can do what a $150,000 mortar fire mission used to, you don't just change the squad's kit—you change the entire fires ecosystem. Watch for infantry units to start bypassing traditional fire-support channels entirely.