Claude Monet: The Man Who Painted Light Until It Blinded Him

Here's the thing about Monet that most people get wrong: he wasn't trying to paint pretty pictures. He was running a decades-long experiment in human perception. When he placed a stroke of pure cobalt blue next to unmixed cadmium yellow on a canvas and let your retina do the mixing, he wasn't being lazy—he was anticipating how digital screens would work a century later. Broken color wasn't a style choice. It was a theory of vision.

The proof is in the series paintings. In the 1890s, Monet started painting the same haystacks, the same cathedral façade, the same stretch of river—over and over, at different hours and in different weather. He'd work on up to fourteen canvases simultaneously at Giverny, switching from one to the next as the light shifted. This wasn't repetition. It was a systematic study of atmosphere that would have made any physicist proud. When Kandinsky saw one of the Haystacks and couldn't identify the subject, the seed of abstract art was planted.

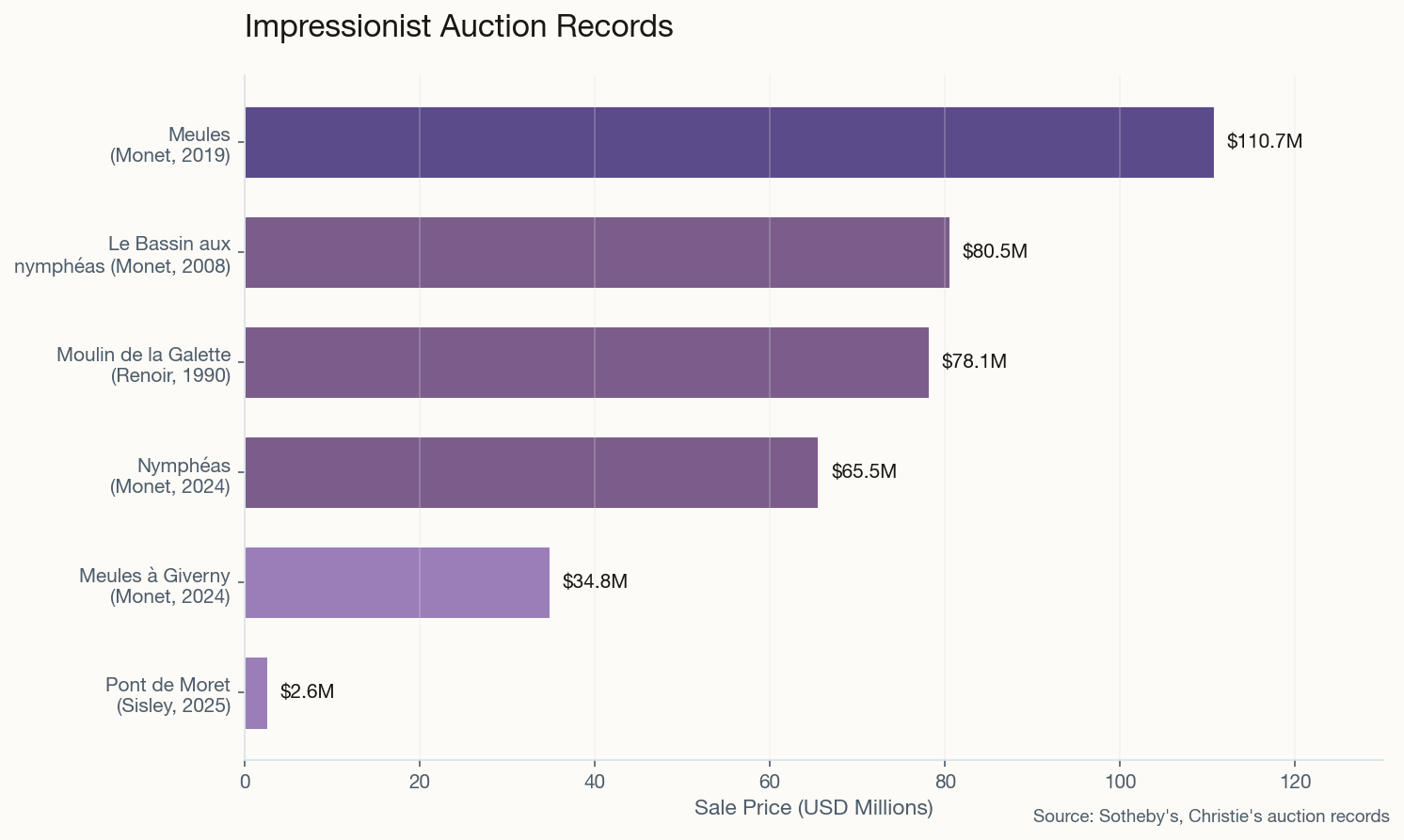

Then cataracts came for his eyes. From 1908, his world turned muddy and reddish-yellow. The late Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge paintings are essentially abstract—swirling, violent, almost expressionist. Critics dismissed them as the fumbling of a blind old man. Half a century later, Abstract Expressionists like Pollock and Rothko would claim him as their forefather. After cataract surgery in 1923, Monet briefly perceived ultraviolet light and painted water lilies in unearthly electric blues that most humans have never seen. A Nymphéas sold for $65.5 million at Sotheby's in 2024. His Meules holds the all-time Impressionist record at $110.7 million.

"My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece." — Claude Monet, who literally diverted a river to build his water garden at Giverny, planting exotic lilies and curating flower colors to match his palette. He didn't paint nature. He grew his paintings.