Hawass Promises a Discovery That Will "Rewrite History"—and Menkaure Just Got More Interesting

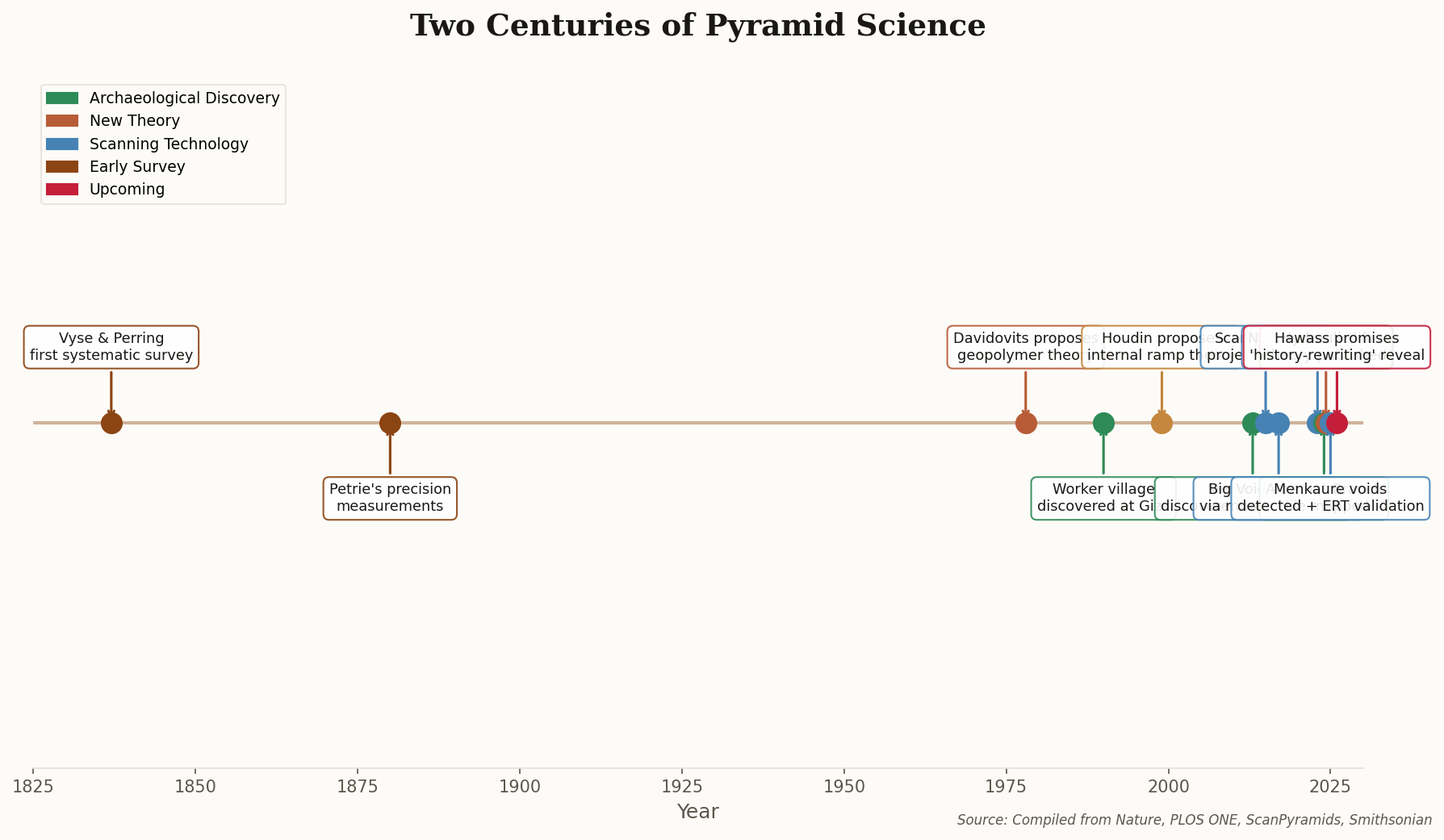

Zahi Hawass doesn't do subtle. Speaking at the 44th Sharjah International Book Fair, Egypt's most recognizable archaeologist declared that a forthcoming 2026 announcement from the Great Pyramid will "write a new chapter in the history of the pharaohs." Robots have now cleaned and reached openings in a newly identified 30-meter corridor that humans couldn't previously access. The corridor's contents remain undisclosed pending a full scientific report.

That alone would be the year's biggest archaeological tease. But November also delivered something more concrete: a team from Cairo University and the Technical University of Munich published findings of two previously unknown air-filled cavities behind the eastern facade of the Pyramid of Menkaure—the smallest of Giza's three great pyramids. The first void measures about 1.5 meters wide by 1 meter high; the second is slightly smaller. Numerical simulations confirmed these aren't natural cracks. Egyptologists have suspected a second entrance on Menkaure's eastern face for decades. They may have just found it.

What matters here isn't just the voids themselves—it's the convergence. Non-invasive scanning technologies are opening pyramids without lifting a single stone. The ScanPyramids project's muon tomography gave us the Big Void in 2017, the North Face Corridor in 2023, and now Menkaure's hidden anomalies. Every scan reveals more architecture than anyone expected. The pyramids are more complex than they appear from outside, and we've barely begun cataloguing what's inside them.

The question isn't whether there's more to find inside the pyramids. It's how much of what we thought we knew about their internal architecture will survive the next decade of scanning.