The 91% Ceiling Nobody Actually Hit

Before we talk about where tax rates went over the last fifty years, we need to talk about where they came from. In 1944, the top marginal rate hit 94% on income above $200,000 — roughly $3.4 million in today's dollars. It wasn't a typo. It was a war.

After V-J Day, that rate settled to 91% and stayed there for nearly two decades. Presidents Eisenhower, a Republican, governed comfortably under it. The interstate highway system, the GI Bill's education boom, the entire postwar American middle class — all built under a tax code that theoretically took nine cents on every dime earned above the top threshold.

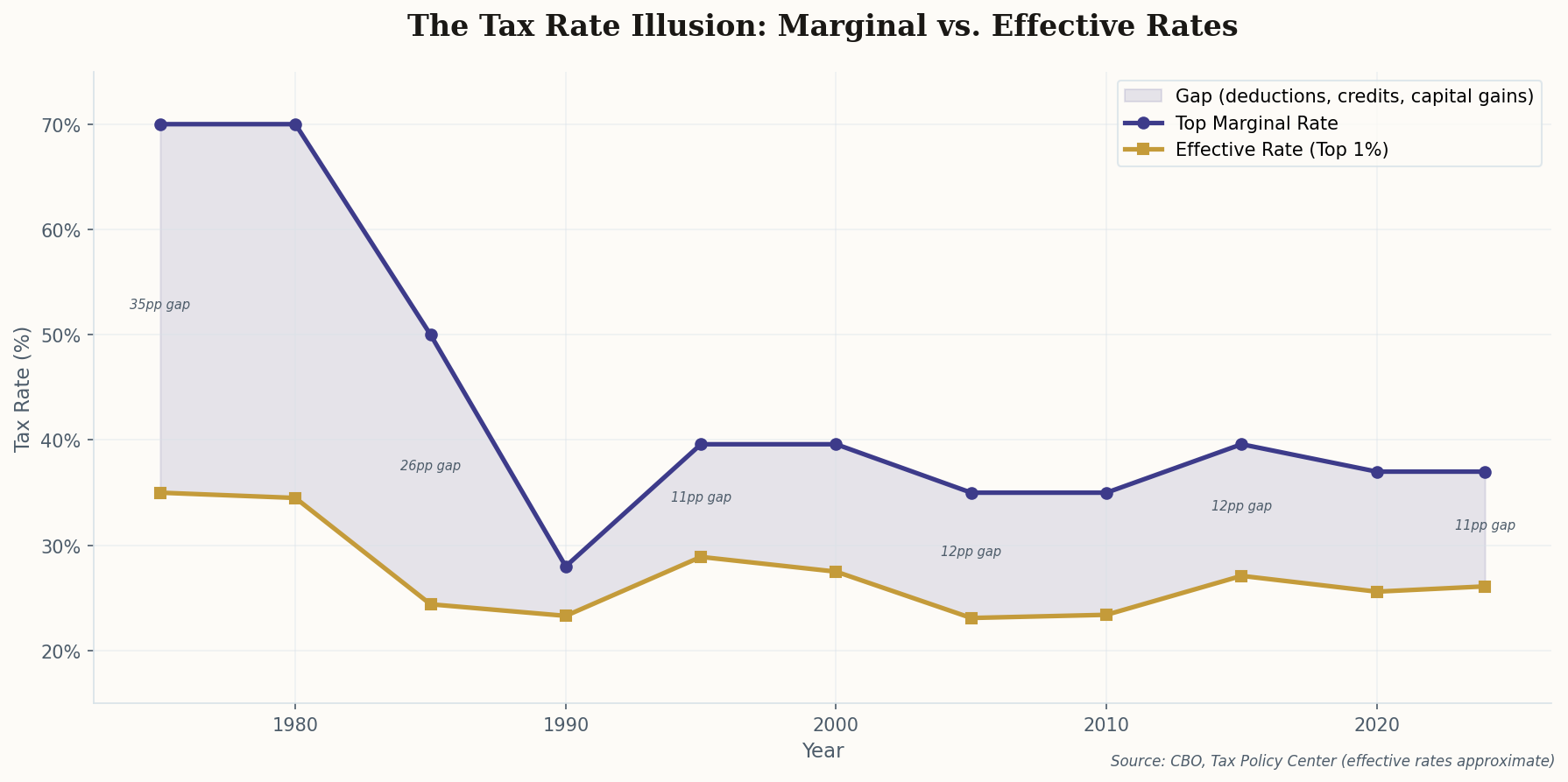

The operative word is "theoretically." Effective tax rates for the top 1% during this era were closer to 42% — still high by modern standards, but a far cry from 91%. The tax code was riddled with deductions, shelters, and loopholes that existed precisely because the statutory rates were so extreme. Municipal bonds, oil depletion allowances, real estate depreciation — the wealthy didn't pay 91%. They paid their accountants.

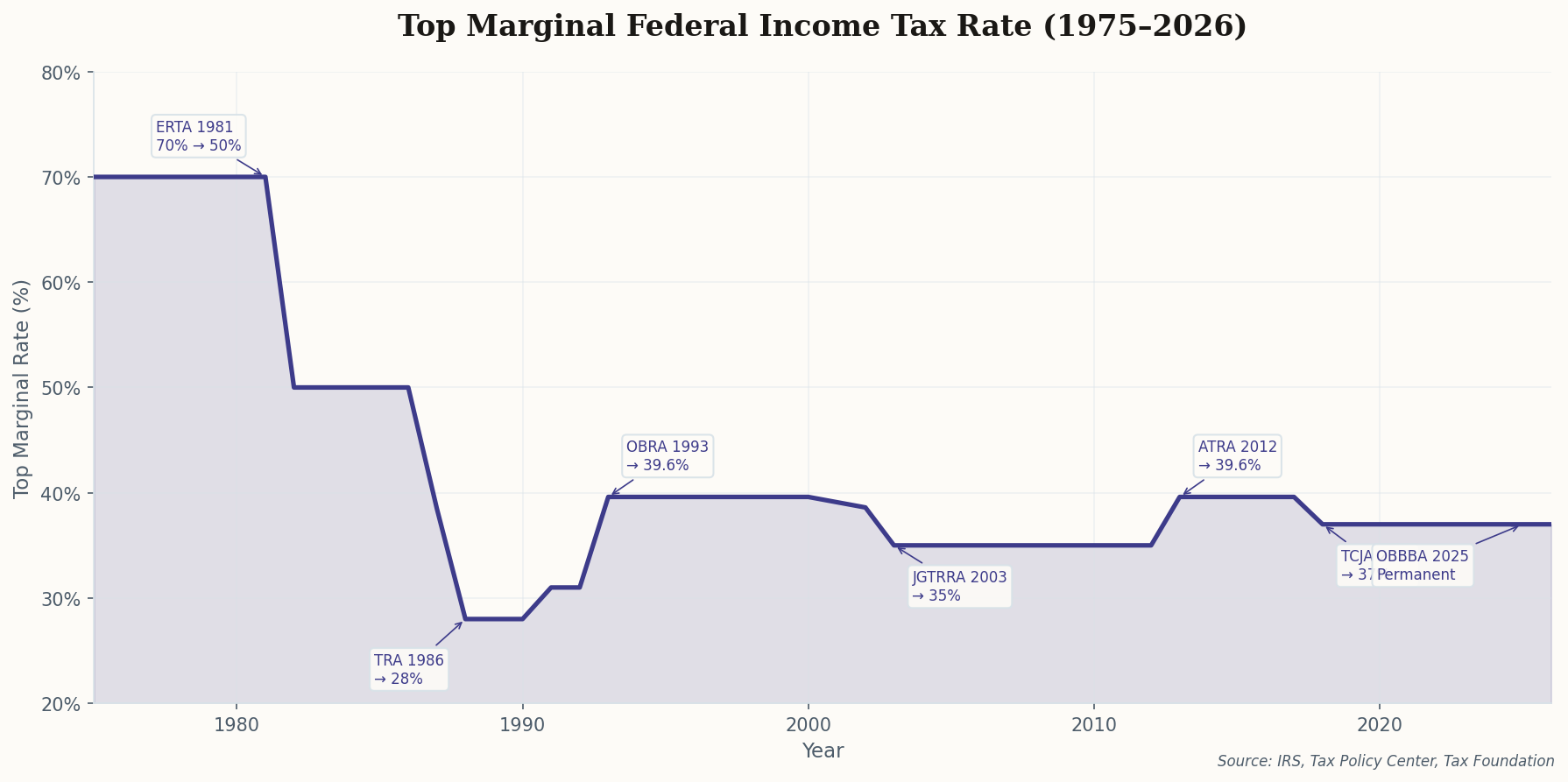

Then JFK proposed cutting the top rate to 65%. He was assassinated before it passed, but LBJ signed the Revenue Act of 1964, bringing the top rate to 70%. It was framed as a stimulus: lower the rates, broaden the base, grow the economy. Sound familiar? It should — this exact argument would recur in 1981, 2001, 2003, 2017, and 2025. The only thing that changes is the starting number.