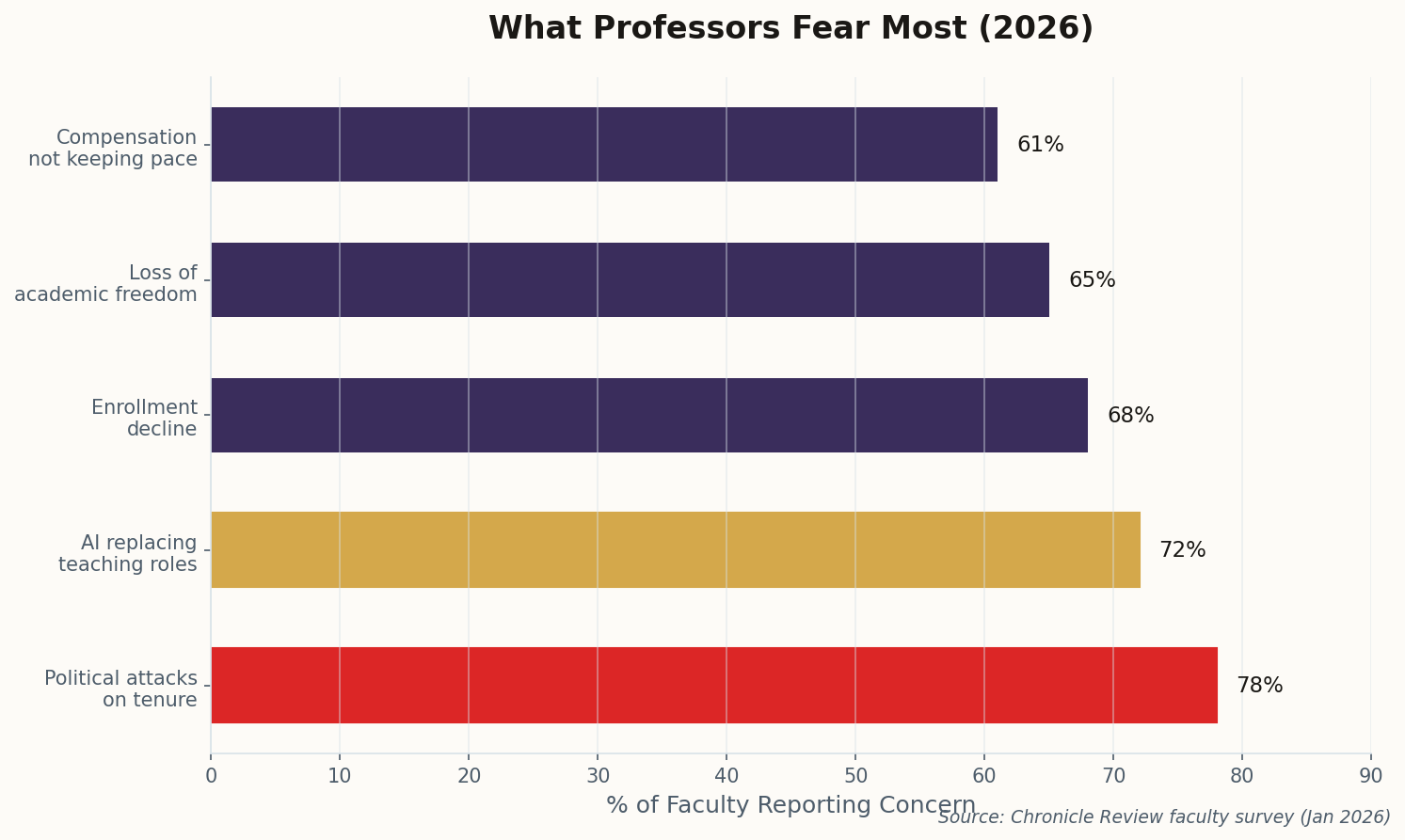

$1.5 Billion in Research Grants Killed

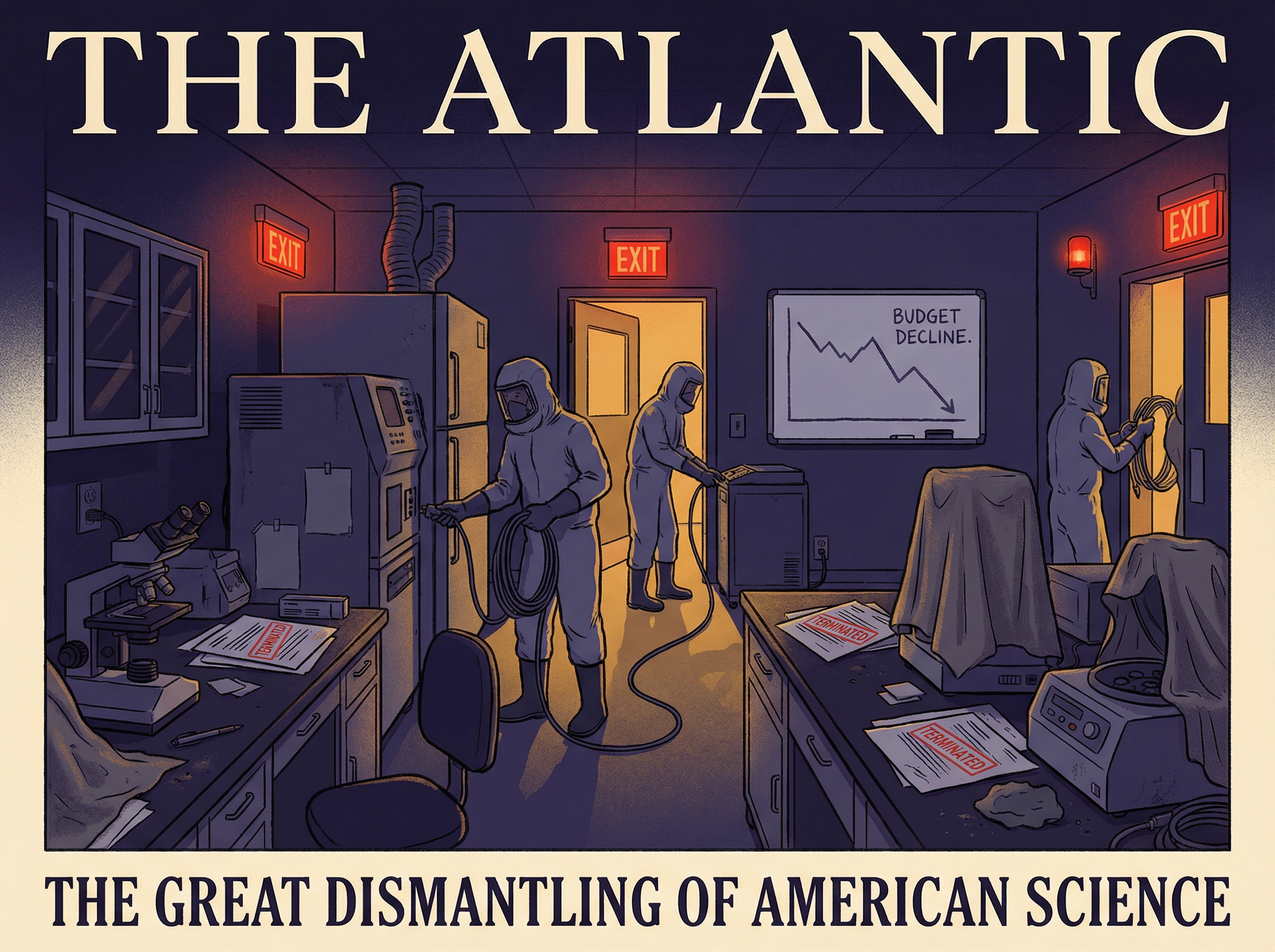

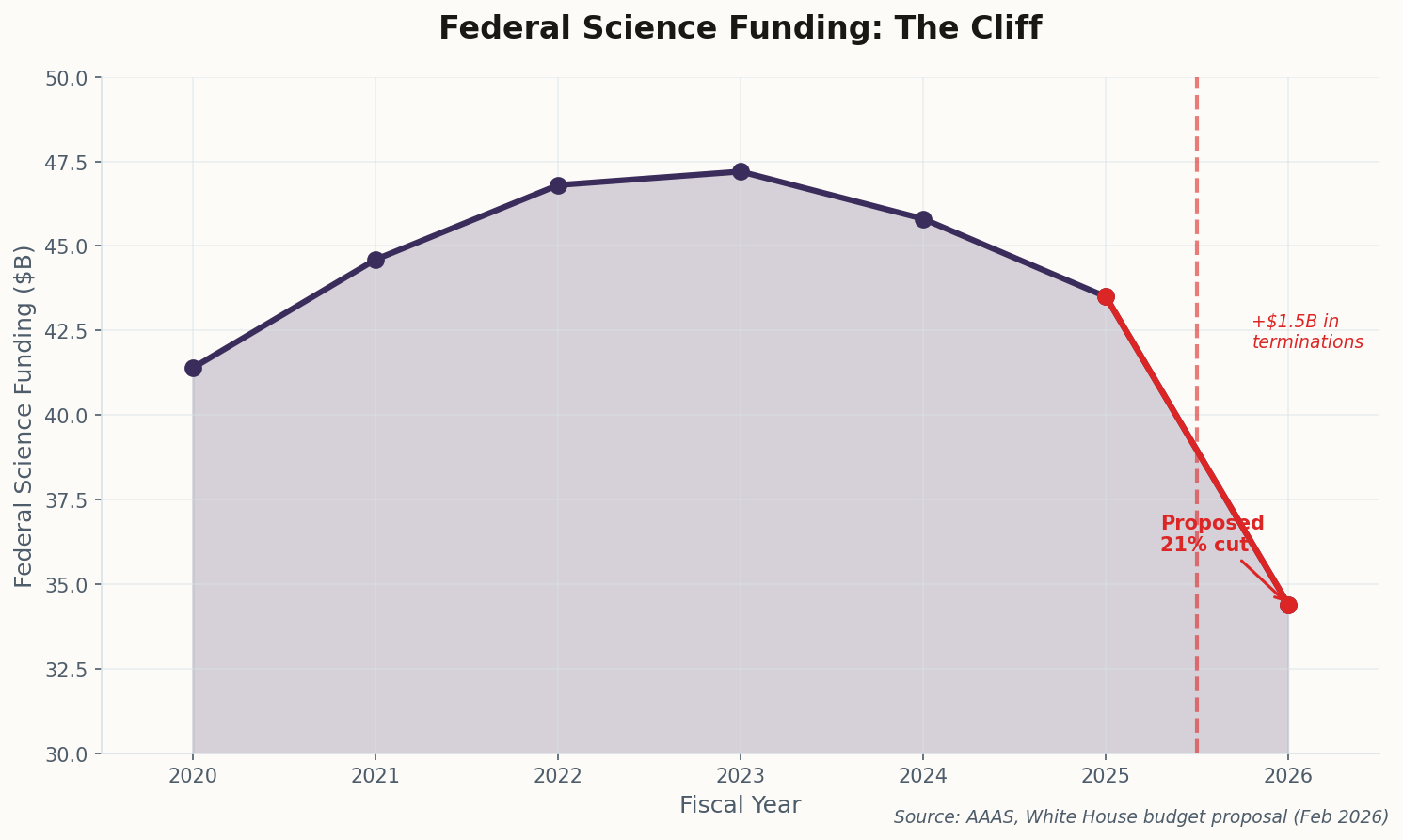

The numbers are no longer abstract. The administration has terminated over $1.5 billion in existing federal research grants, targeting work it characterizes as "ideologically driven" or DEI-related. Simultaneously, the White House budget proposal calls for a 21% reduction in federal science funding for fiscal year 2026.

The retroactive cancellations are particularly devastating. These aren't hypothetical future grants—they're funded, active research programs with graduate students mid-dissertation, postdocs mid-contract, equipment already purchased. Labs are shutting down experiments that took years to design. Principal investigators are scrambling to place displaced researchers.

The compounding effect: Grant terminations don't just stop current work—they destroy the pipeline. Graduate students who see funded labs close don't enter the field. Postdocs leave for industry. Senior researchers retire early. The damage compounds over decades.

The 21% budget cut, if enacted, would return federal science funding to levels not seen since before the Obama administration. Combined with the terminations, it signals that the research university as Americans have known it since World War II—government-funded, globally competitive, driving innovation—may be entering a fundamentally different era.