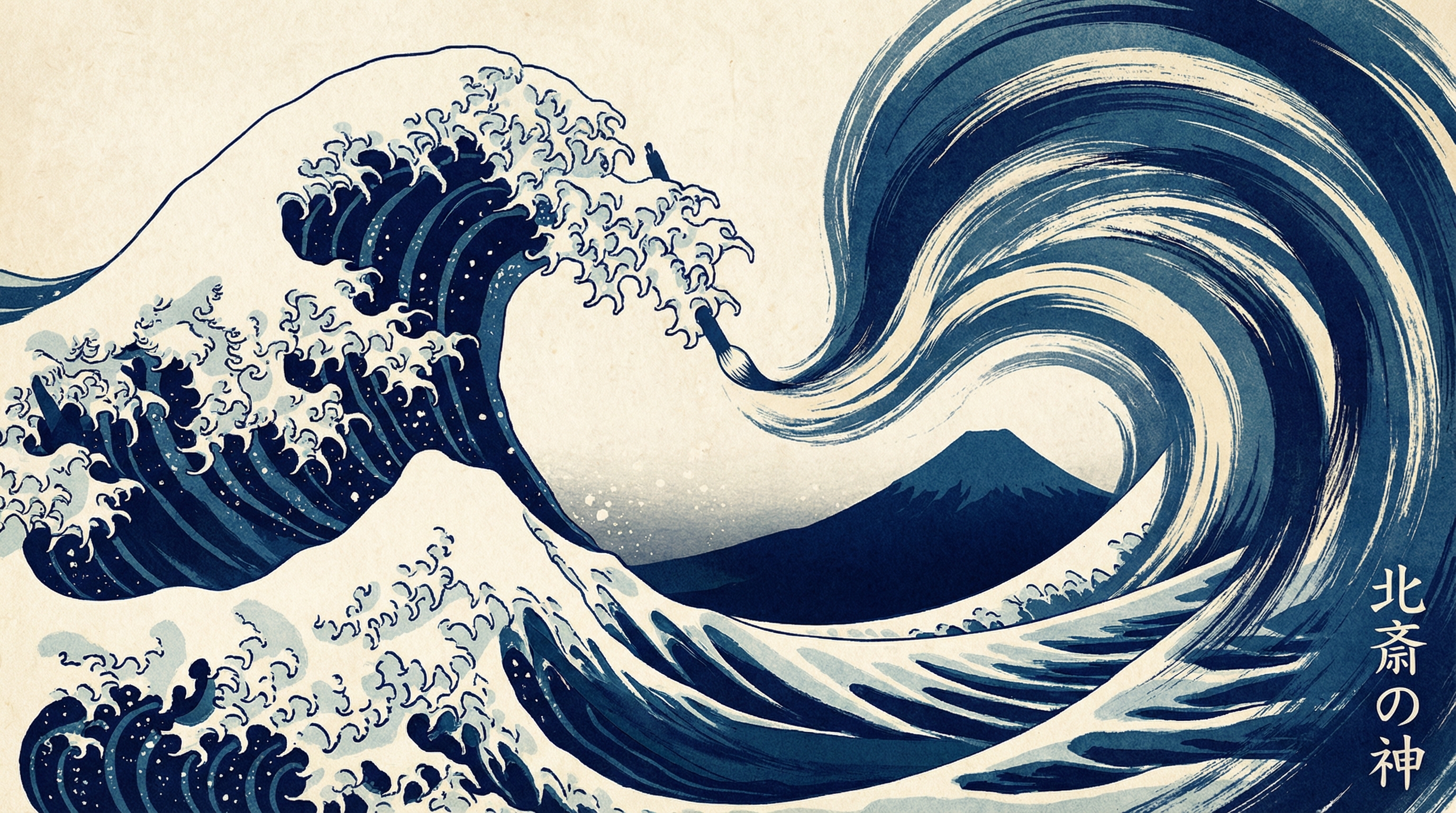

A Wave Worth $2.8 Million

When the hammer fell at Sotheby's Hong Kong in November 2025, a single sheet of mulberry paper printed nearly 200 years ago fetched HK$21.7 million—roughly $2.8 million USD. The work? The Great Wave off Kanagawa, Hokusai's immortal image of a towering wave threatening tiny fishing boats as Mount Fuji sits serenely in the distance.

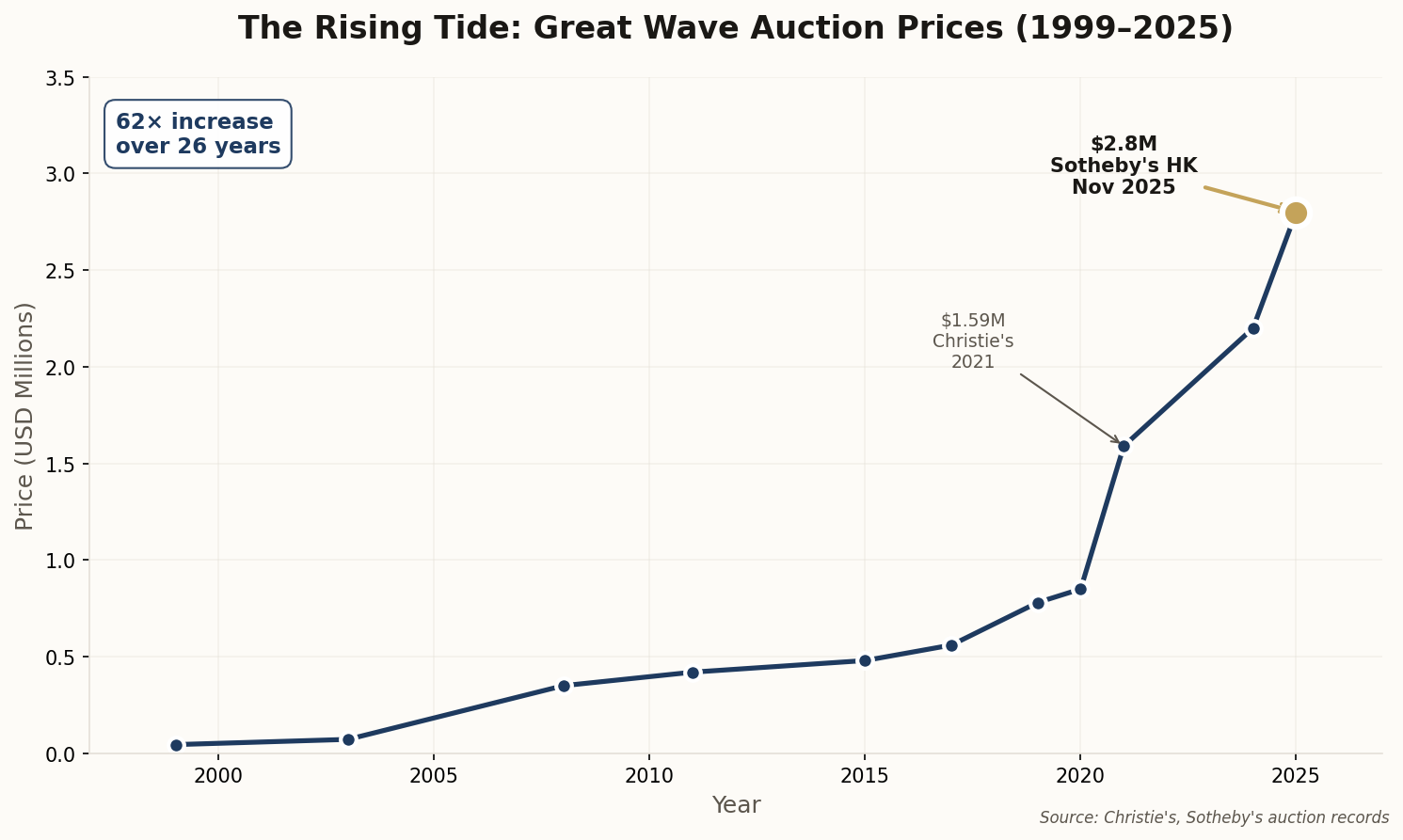

This wasn't just another art sale. It was a 62× increase from 1999, when exceptional impressions of the same print sold for around $45,000. The exponential rise speaks to something beyond collector speculation: Hokusai's wave has become a cultural artifact that transcends art history.

What makes a 190-year-old woodblock print worth as much as a Manhattan apartment? Rarity, certainly—fine impressions are scarce. But the deeper answer is reach. The Great Wave appears on coffee mugs, phone cases, tattoos, and museum walls across every continent. It's the rare artwork that works equally well at 2 inches or 20 feet. That universality has made it priceless precisely because it's everywhere.