Before There Was a Kingdom, There Were Tombs

Long before the first barrel of oil changed everything, the Arabian Peninsula was the connective tissue of the ancient world. The Dilmun civilization, centered in the Eastern Province and modern-day Bahrain, operated as a trade nexus between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley as early as the 3rd millennium BCE. These weren't desert nomads scraping by — they were middlemen in the most profitable trade network on earth.

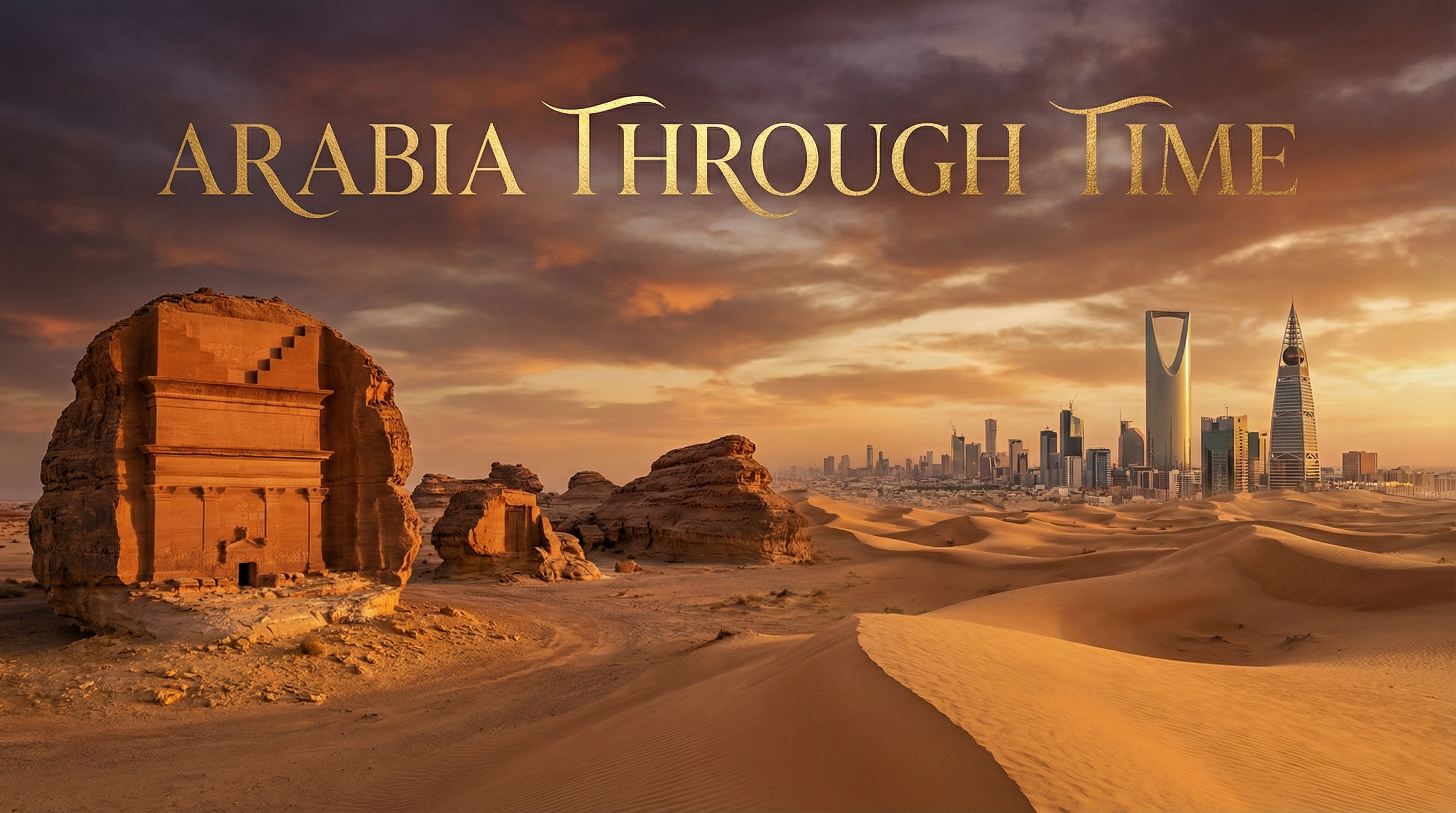

The real showstopper is Hegra (Mada'in Saleh), Saudi Arabia's first UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Nabataean Kingdom carved over 111 monumental tombs directly into sandstone outcrops here — a southern mirror of their more famous capital at Petra. From the 4th century BCE to 106 CE, these master builders controlled the Incense Route, the ancient superhighway that moved frankincense and myrrh from Yemen to Mediterranean ports. The profit margins on incense were, by some accounts, comparable to the spice trade that would later drive European colonialism.

The Thamud people, mentioned in both the Quran and Assyrian records, left their mark across the northern Hejaz in rock inscriptions and carved dwellings. And then came the camel — its domestication turned the Empty Quarter from an impassable barrier into a traversable, if still terrifying, trade corridor connecting the Indian Ocean world with Rome and Byzantium. The peninsula wasn't isolated. It was a hub.

The throughline: Saudi Arabia's current push to become a global tourism destination isn't reinvention — it's restoration. Hegra drew visitors and traders for centuries before anyone knew what was underneath the sand.