The Consensus That Took 80 Years

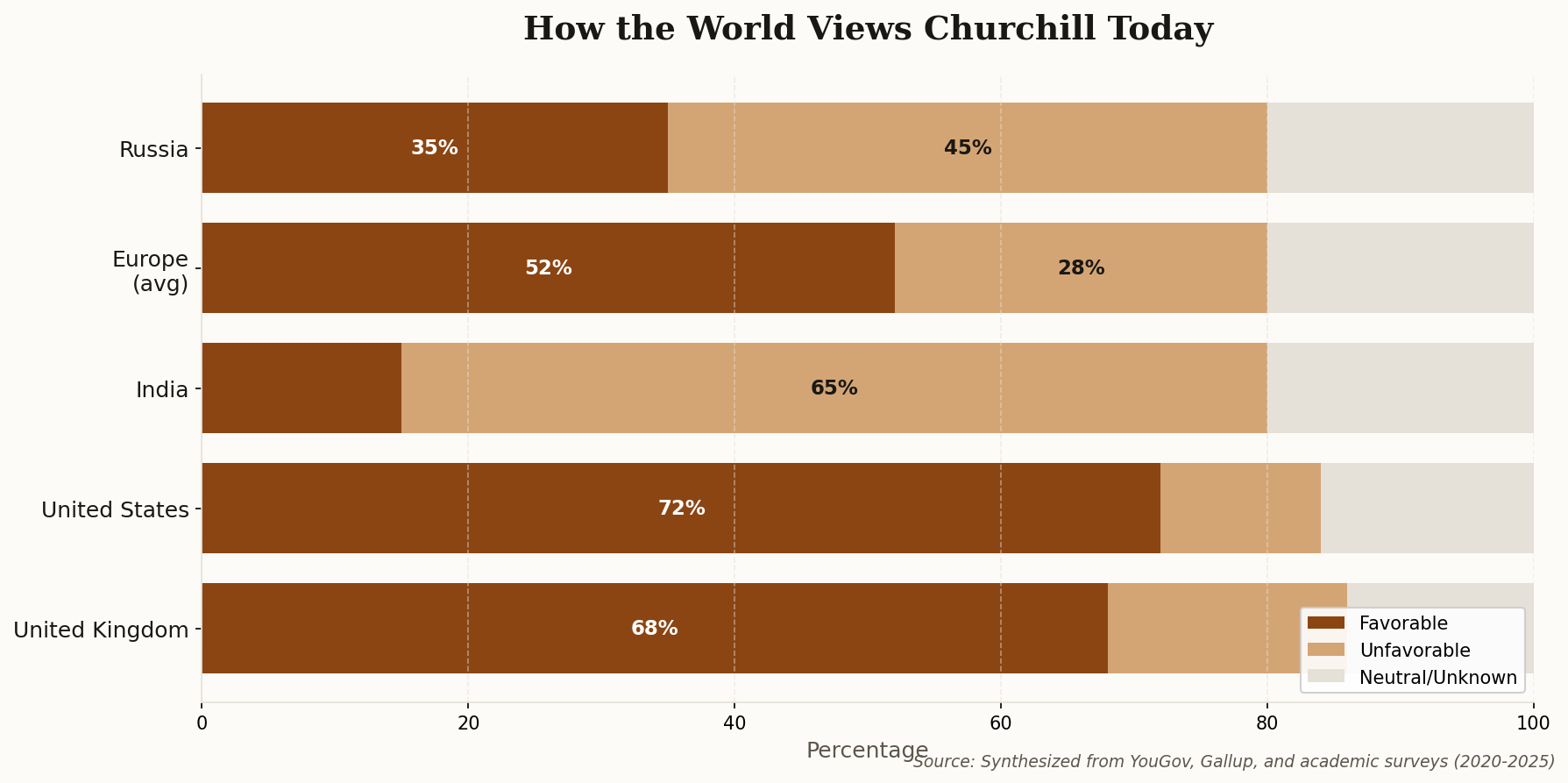

For decades, Churchill biography was a binary game. You were either in the Hillsdale College camp—defender of Western civilization, lion against fascism—or you were reading Tariq Ali's counter-narrative of imperial crimes. The middle ground felt like cowardice.

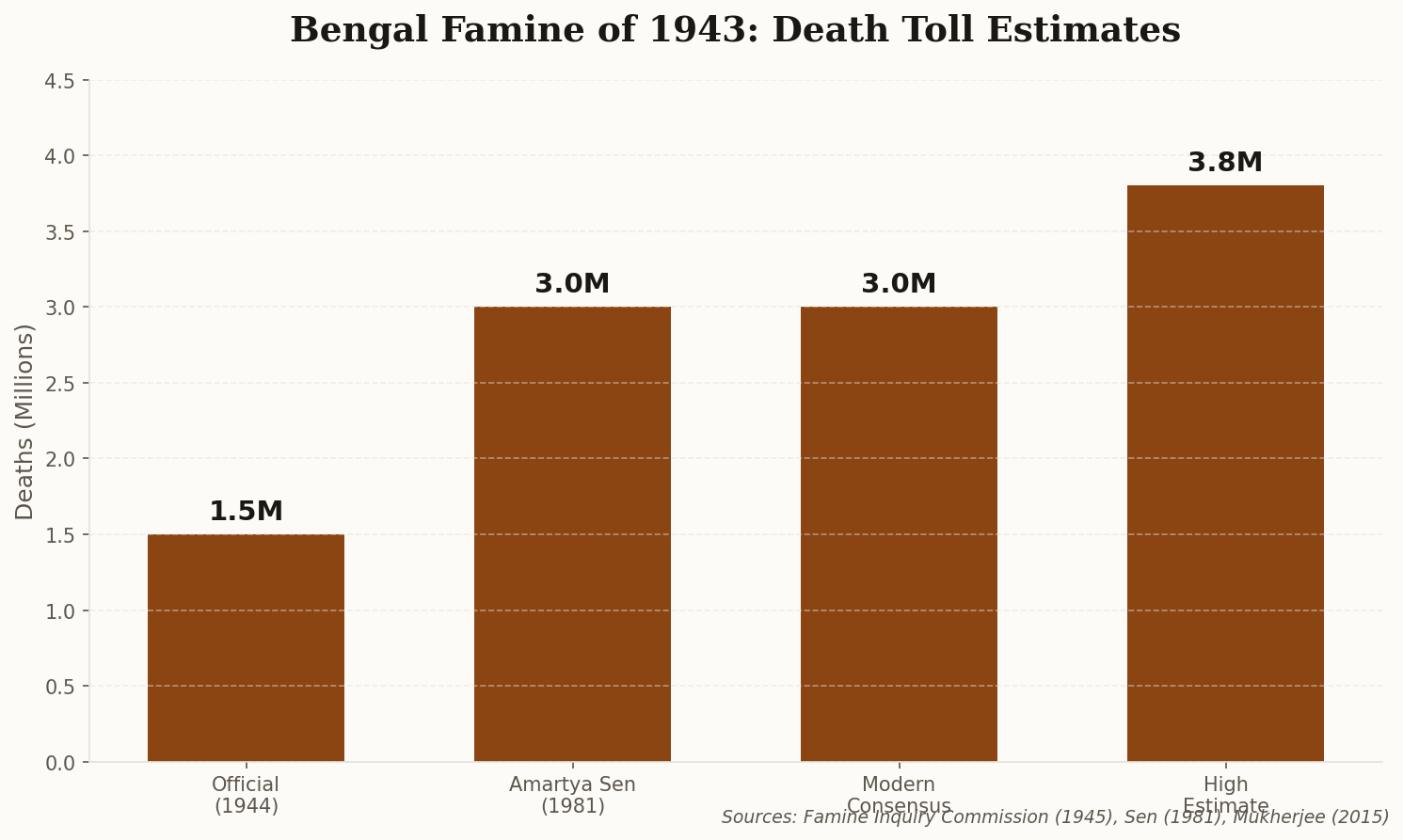

By 2026, the historical profession has arrived somewhere more uncomfortable: both are true. The same man who held Britain together in 1940 oversaw policies that caused millions of deaths in Bengal. The voice that rallied democracy against tyranny also believed, explicitly and in writing, that Indians were "a beastly people with a beastly religion."

This isn't moral relativism. It's the mature recognition that historical figures contain multitudes, and that whitewashing Churchill does as much disservice to understanding World War II as condemning him does to understanding colonial history. The flawed giant isn't a compromise position—it's the only honest one.

The key shift: Pre-2020, "complexity" was often code for avoiding hard conclusions. Post-2020, it means holding two true things at once—and being uncomfortable with both.