The Skiers Who Talked the Army Into a War

In February 1940, four men sat by a roaring fire at the Orvis Inn in Manchester, Vermont, and conceived what would become the most improbable division in the United States Army. They had just watched Finnish ski troops humiliate the invading Soviet Red Army, and one thought kept nagging: the U.S. had nothing remotely comparable.

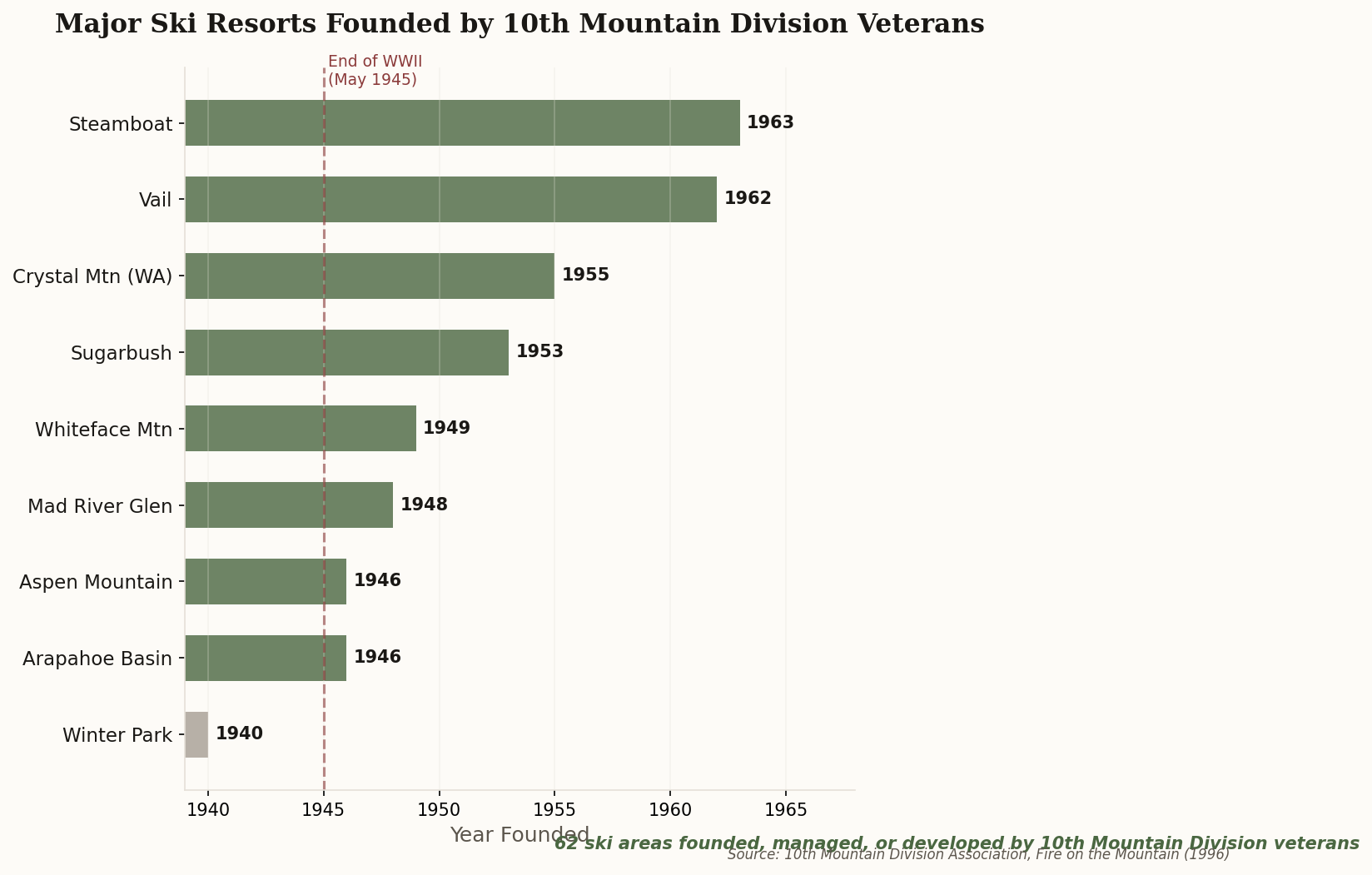

Charles Minot Dole, founder of the National Ski Patrol, decided to do something about it. He lobbied the War Department relentlessly, and in October 1941, General George C. Marshall handed Dole a mandate unlike anything in military history: recruit your own army unit. The reasoning was elegant — it was easier to train skiers to fight than to train soldiers to ski.

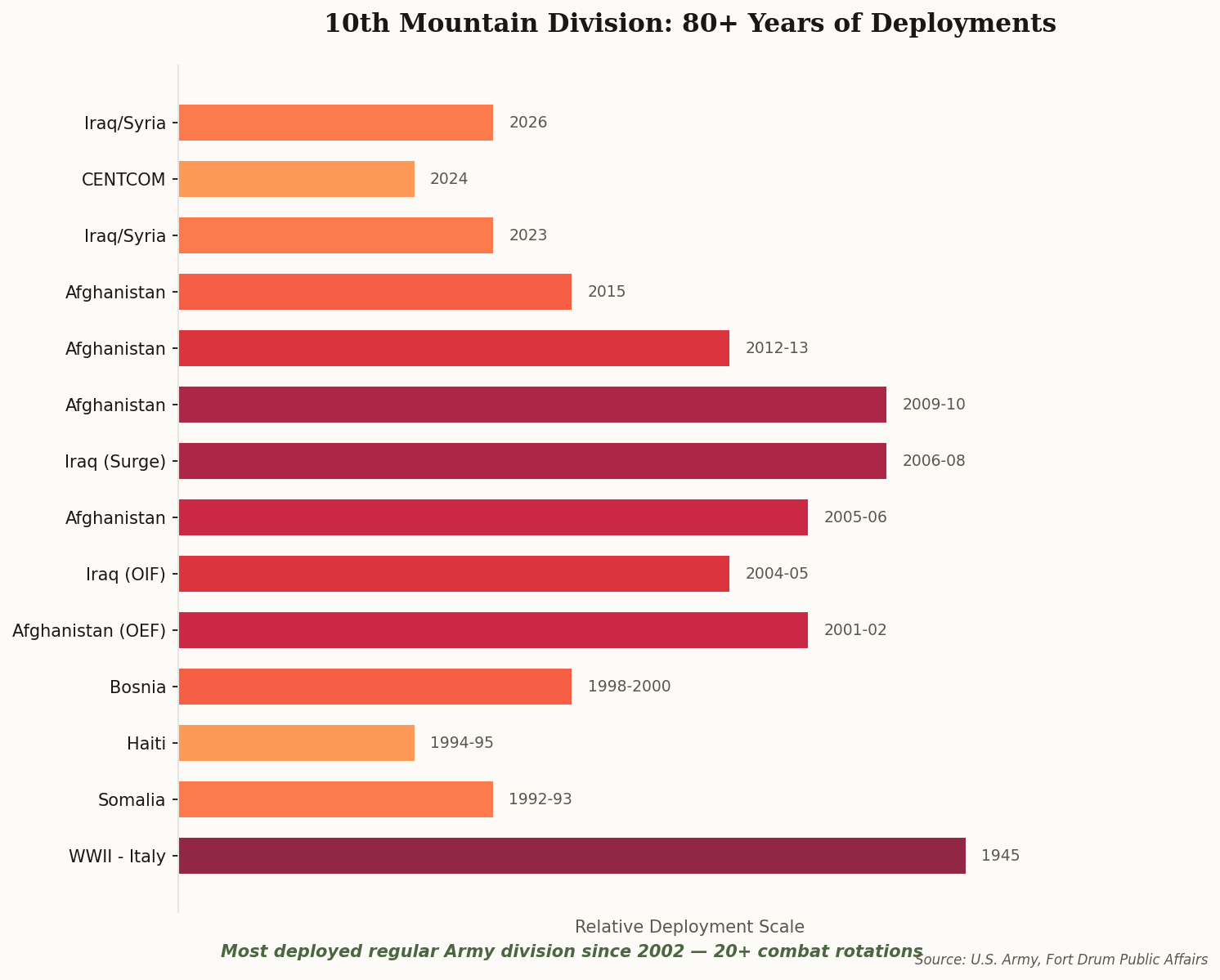

On December 8, 1941 — one day after Pearl Harbor — the Army activated its first mountain unit, the 87th Mountain Infantry Battalion, at Fort Lewis, Washington. The National Ski Patrol became the only civilian organization in American military history to serve as a recruiting agency. By July 1943, with three regiments organized, the unit gained divisional status at Camp Hale, Colorado — initially as the 10th Light Division (Pack Alpine), acquiring its iconic name, the 10th Mountain Division, in November 1944.

What made the recruiting genuinely remarkable was who showed up. Ivy League skiers rubbed shoulders with Norwegian immigrants who'd fled the Nazis, Austrian mountaineers, Colorado miners, Vermont lumberjacks, and Western cowboys. Olympic athletes signed up alongside ranchers who'd never seen a ski lift. It was a division built on a shared love of mountains rather than geography, class, or convention. The Army had never tried anything like it — and hasn't since.