AI's Beautiful Slides Might Be Making You Dumber

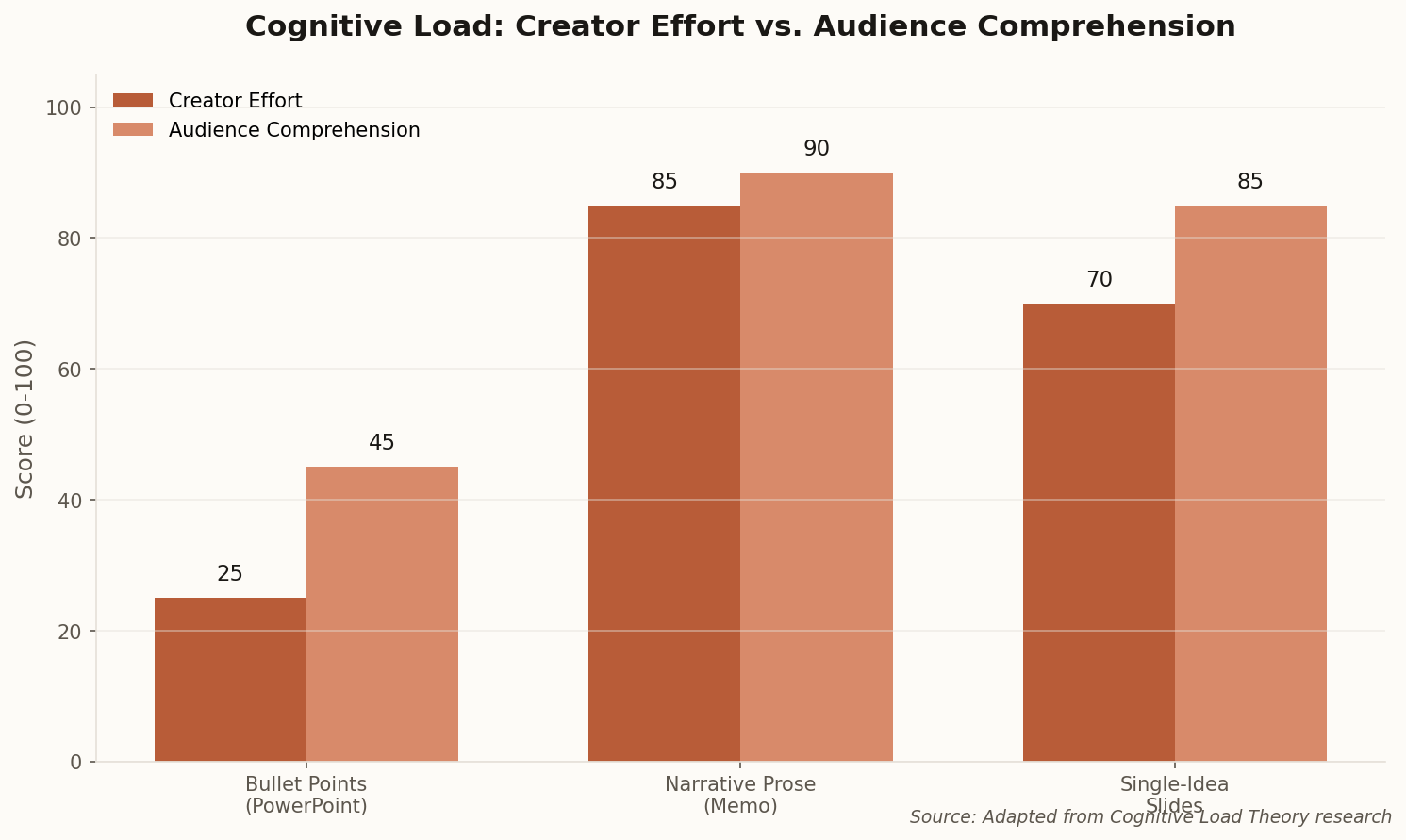

When Gamma can generate a deck in 30 seconds that would take you three hours to create manually, what exactly have you gained? According to a growing body of research, you may have gained a pretty artifact while losing something far more valuable: the cognitive workout that makes you actually understand your material.

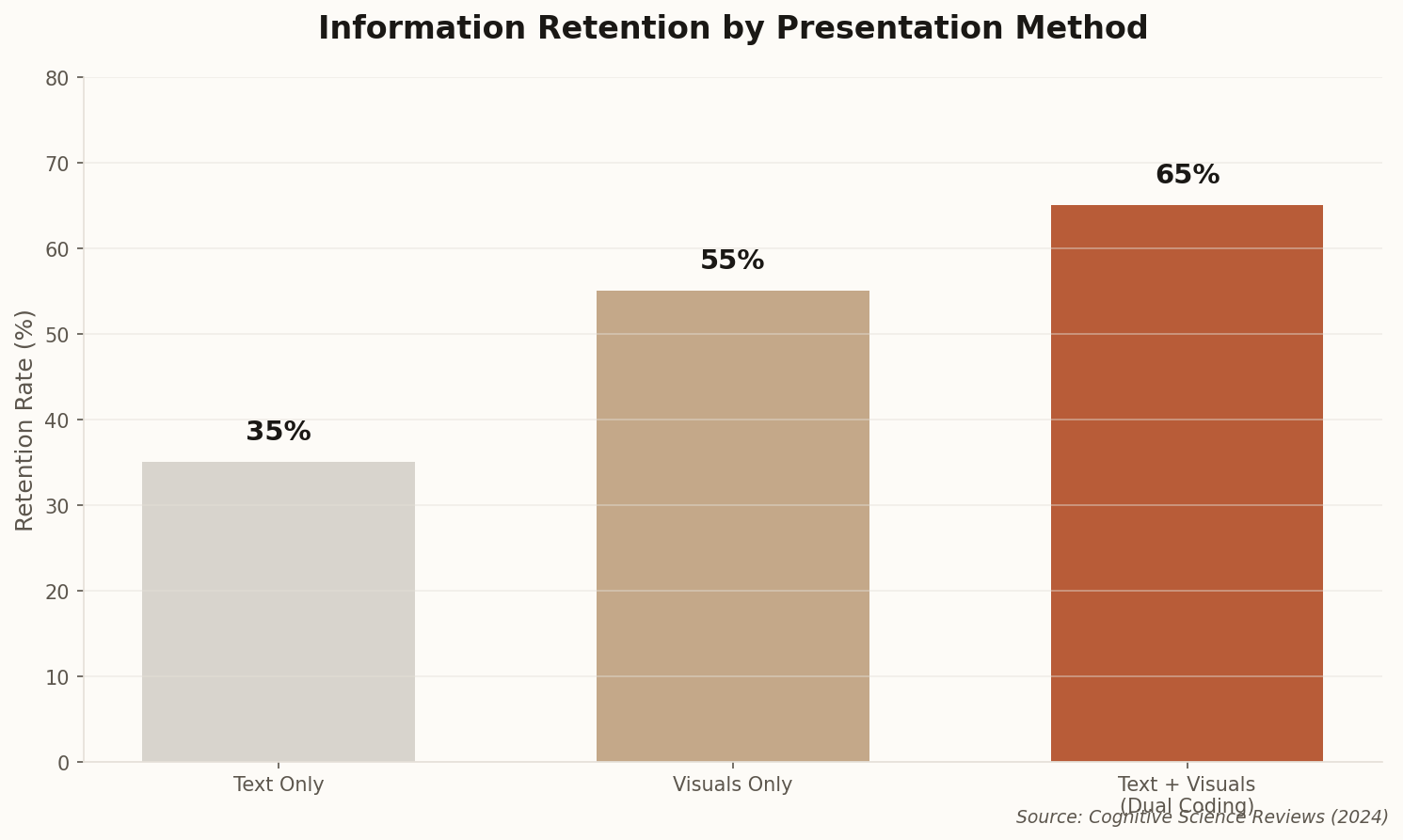

The review of Beautiful.ai and similar tools is glowing on surface metrics—"swift and pleasant," "democratizing design"—but buried in the praise is a critical observation: these tools remove the "friction" that forces authors to refine their logic. When AI layouts prevent you from making "bad" design choices, they also prevent the visual thinking required to map complex relationships spatially.

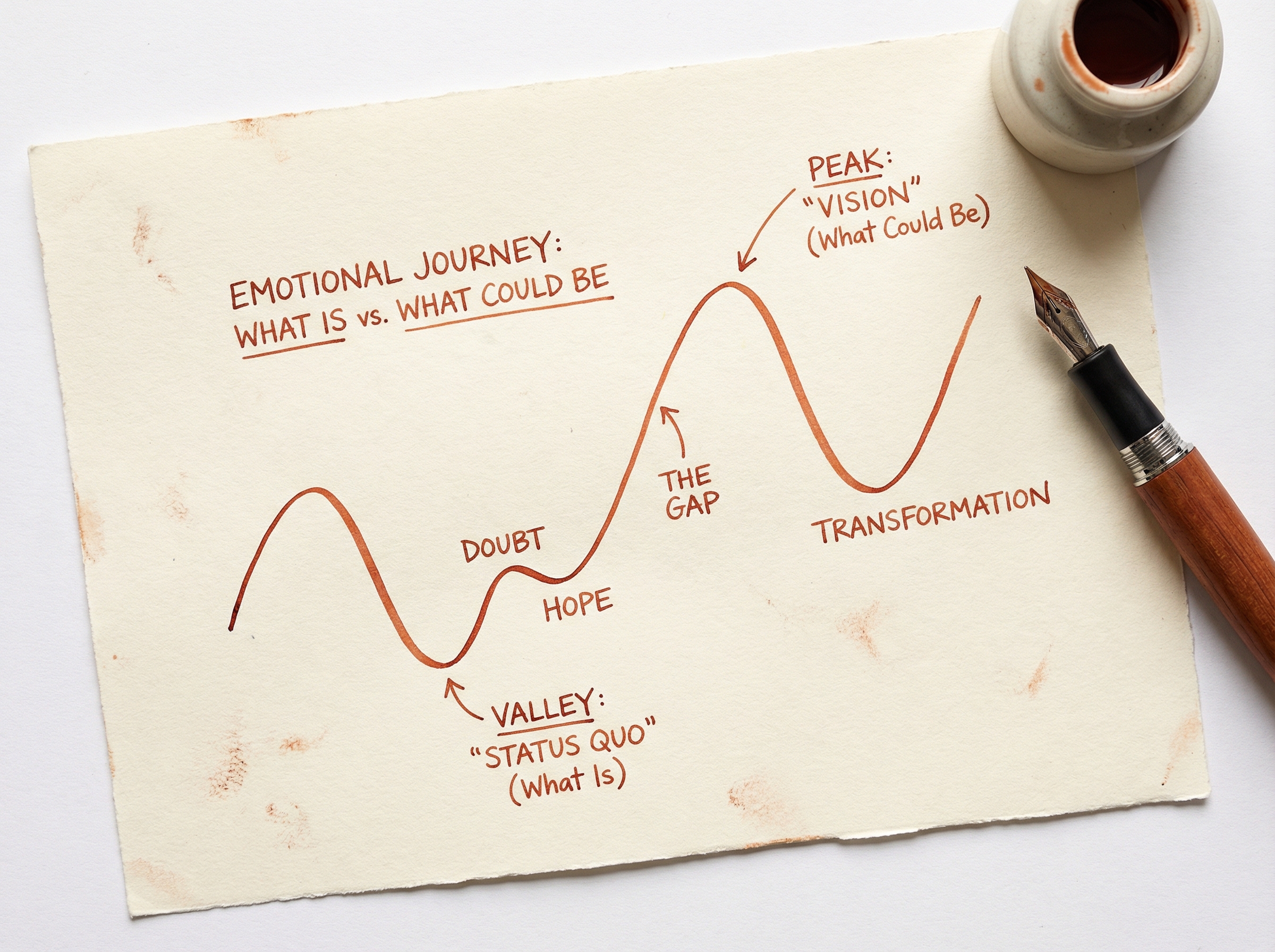

This is the "competence trap" in action. The output looks professional, but the user never grappled with the hard question: What is the one thing I need this audience to understand? That struggle, it turns out, is where understanding crystallizes.

The trade-off: AI removes the drudgery of formatting, but arguably shortcuts the "synthesis struggle" that leads to breakthrough insights. You can have a beautiful deck or a deep understanding—increasingly, the tools are optimizing for the former.