Margot Robbie Just Sold More Brontë Than Amazon Could

Here's a thought experiment: What's the most effective tool for getting Gen Z to read a 179-year-old novel about a vengeful orphan on the Yorkshire moors? Not assigned reading lists. Not TikTok BookTok influencers. Not even that beloved English teacher with the infectious enthusiasm for Romantic literature.

It's Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi in a moody trailer.

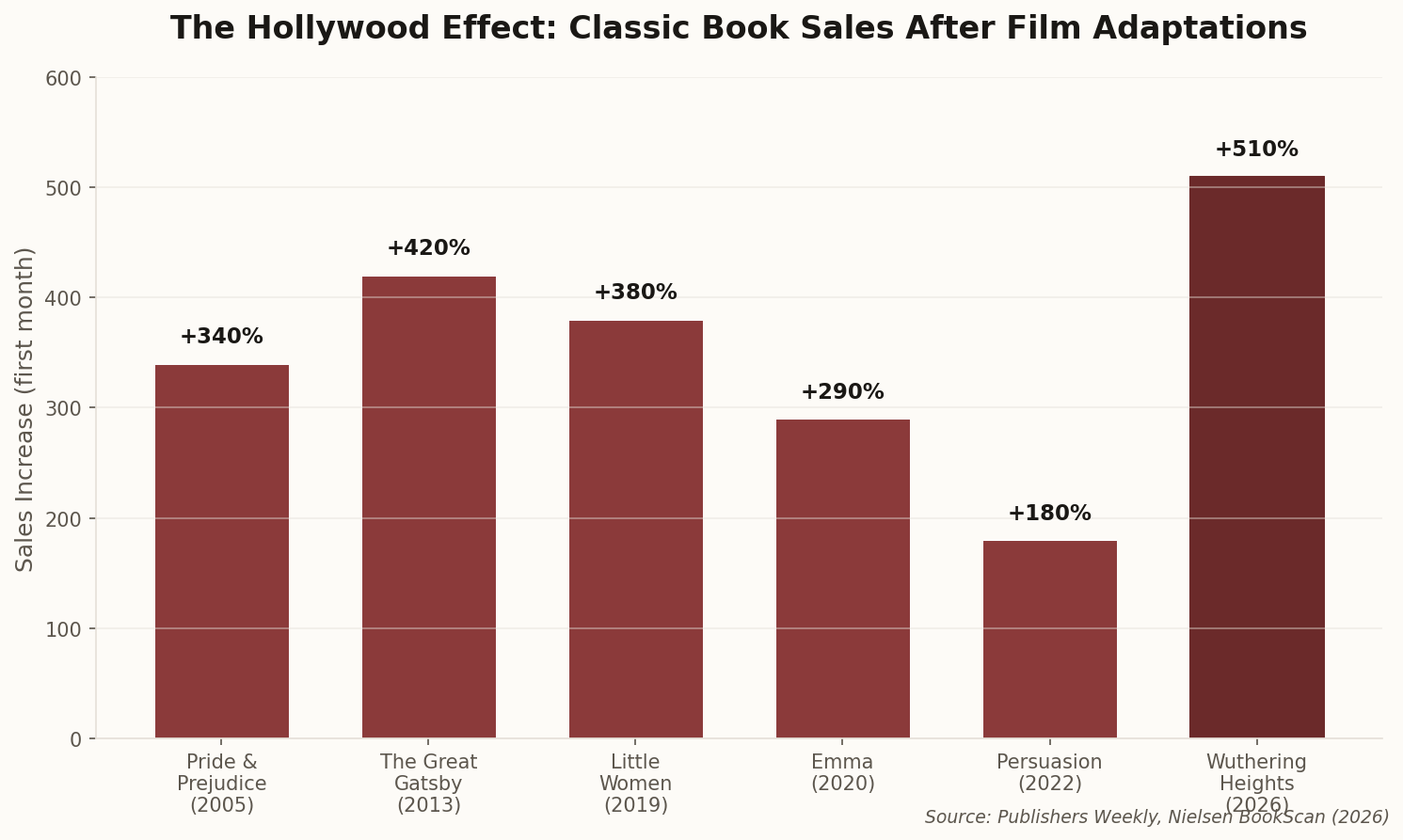

Emerald Fennell's adaptation of Wuthering Heights premiered January 28th, and within 48 hours, sales of Emily Brontë's novel surged over 500% according to Nielsen BookScan. The Puffin in Bloom edition—that's the pretty one with the illustrated cover—crashed onto the YA fiction bestseller list. "It is a story of a monster," Fennell told interviewers, "and I think that is something we are all ready to see."

The cynical take: kids aren't actually reading classics—they're buying pretty editions to photograph for Instagram. The data tells a more interesting story. Post-adaptation sales tend to sustain for 6-8 months, and readers who pick up the source material after seeing an adaptation are more likely to read a second classic within the year. Hollywood isn't replacing the literary canon. It's the most effective gateway we have.