The World's Oldest Spreadsheet Was Written on Papyrus

Forget the romance of whip-cracking overseers and endless rows of straining slaves. The Diary of Merer—the oldest known papyrus in existence—reveals something far more impressive: the ancient Egyptians invented bureaucracy before they invented the wheel.

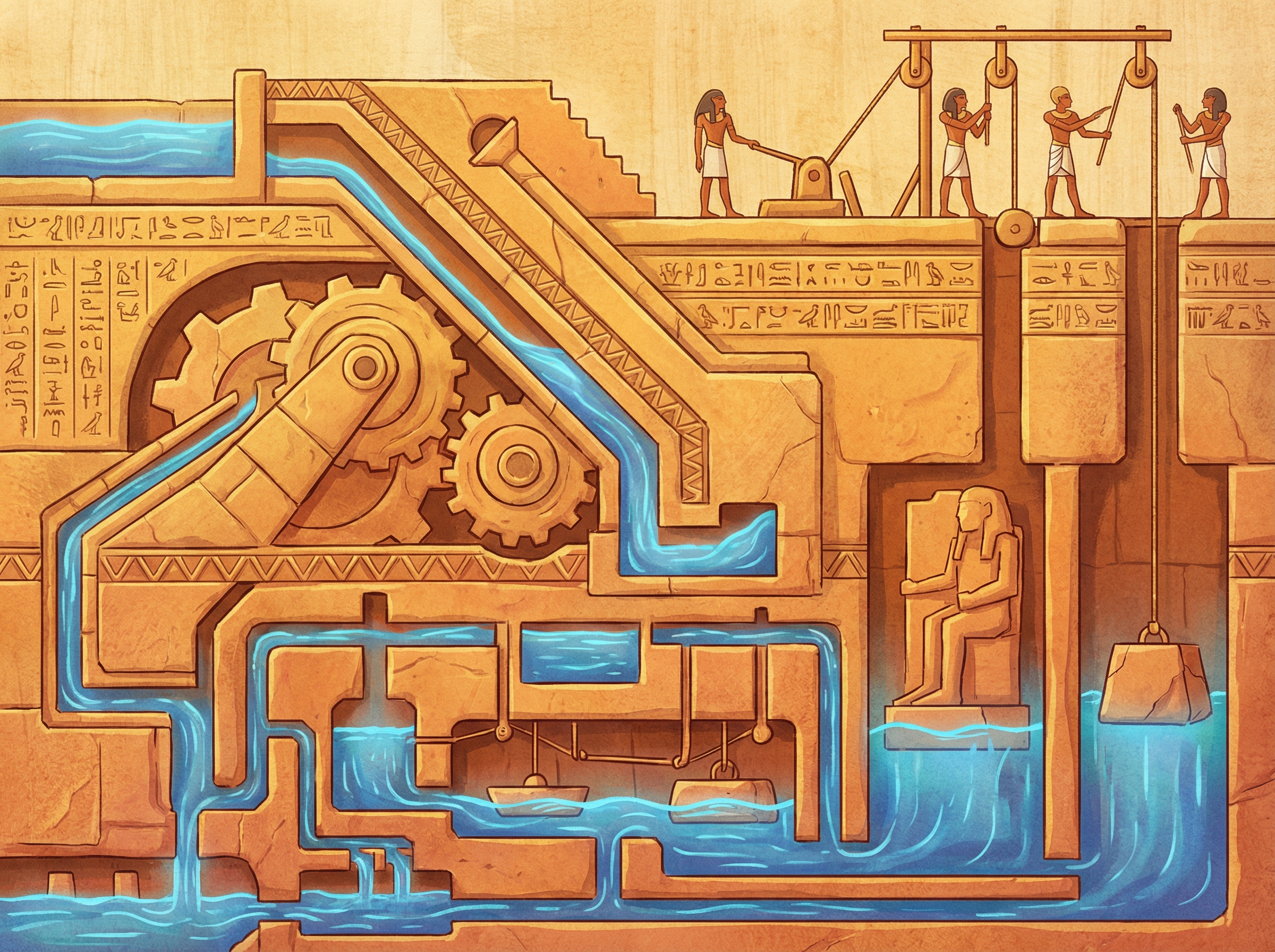

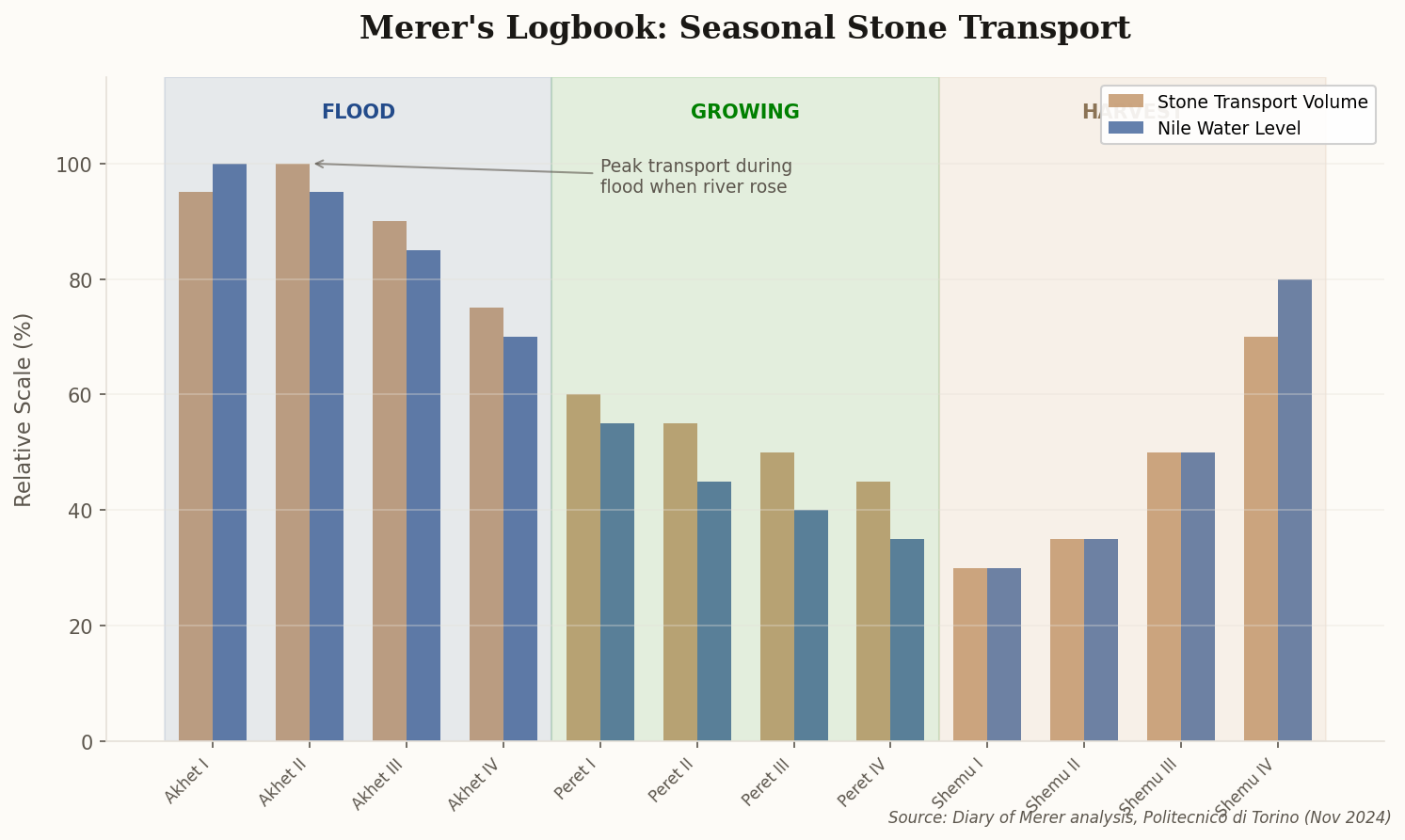

New analysis by researchers at Politecnico di Torino digs into the precise timekeeping recorded in this 4,500-year-old logbook. Merer, an inspector of works, documented his team's daily stone deliveries with the obsessive detail of a modern logistics manager. They worked a strict 10-day week. They tracked tons per boat. They synchronized their labor with the Nile's flood cycle—because when the river rose, the stones could float closer to the construction site.

Merer's team moved 2-3 tons of limestone per boatload. That's not brute force—that's supply chain optimization. The logbook demonstrates that pyramid construction wasn't a feat of raw muscle but of management: centralized scheduling, seasonal adaptation, and what researchers call "a highly centralized and timed management of the workforce, strictly bound to the Egyptian civil calendar."

The takeaway? The pyramids weren't built by slaves or aliens. They were built by middle managers with extremely good calendars.