The Yield Curve Just Started the Clock

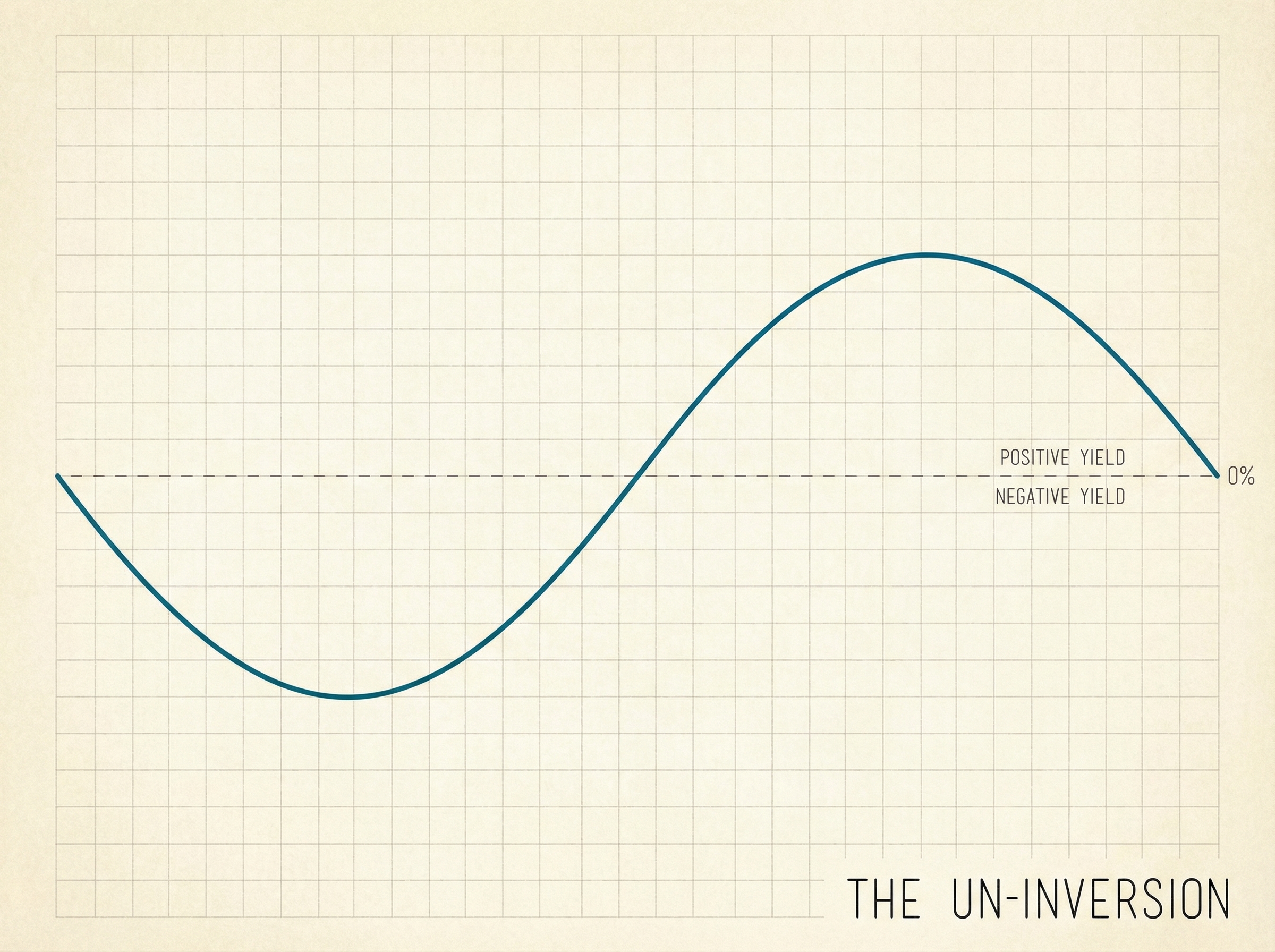

The 10-year minus 2-year Treasury spread has finally "un-inverted"—crossing back into positive territory after one of the longest inversions in modern history. If you're breathing a sigh of relief, don't. The un-inversion is the warning, not the inversion itself.

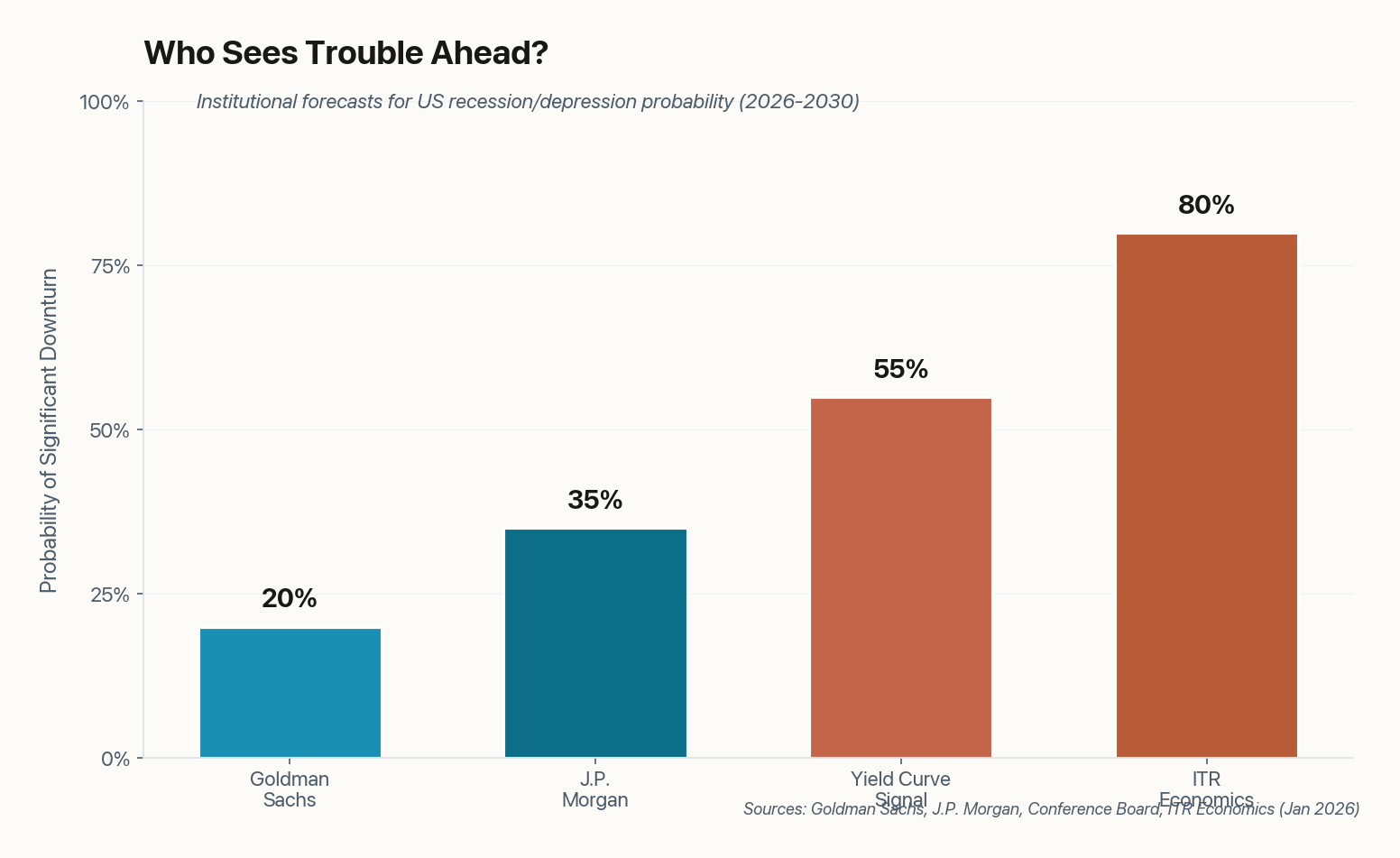

Here's the pattern that's spooked economists for decades: the yield curve inverts, everyone panics, nothing happens for a year or two, people forget about it, and then the recession arrives—usually 6 to 18 months after the curve normalizes. That's exactly where we are now. The Conference Board has been tracking this signal since 1966, and it's never cried wolf.

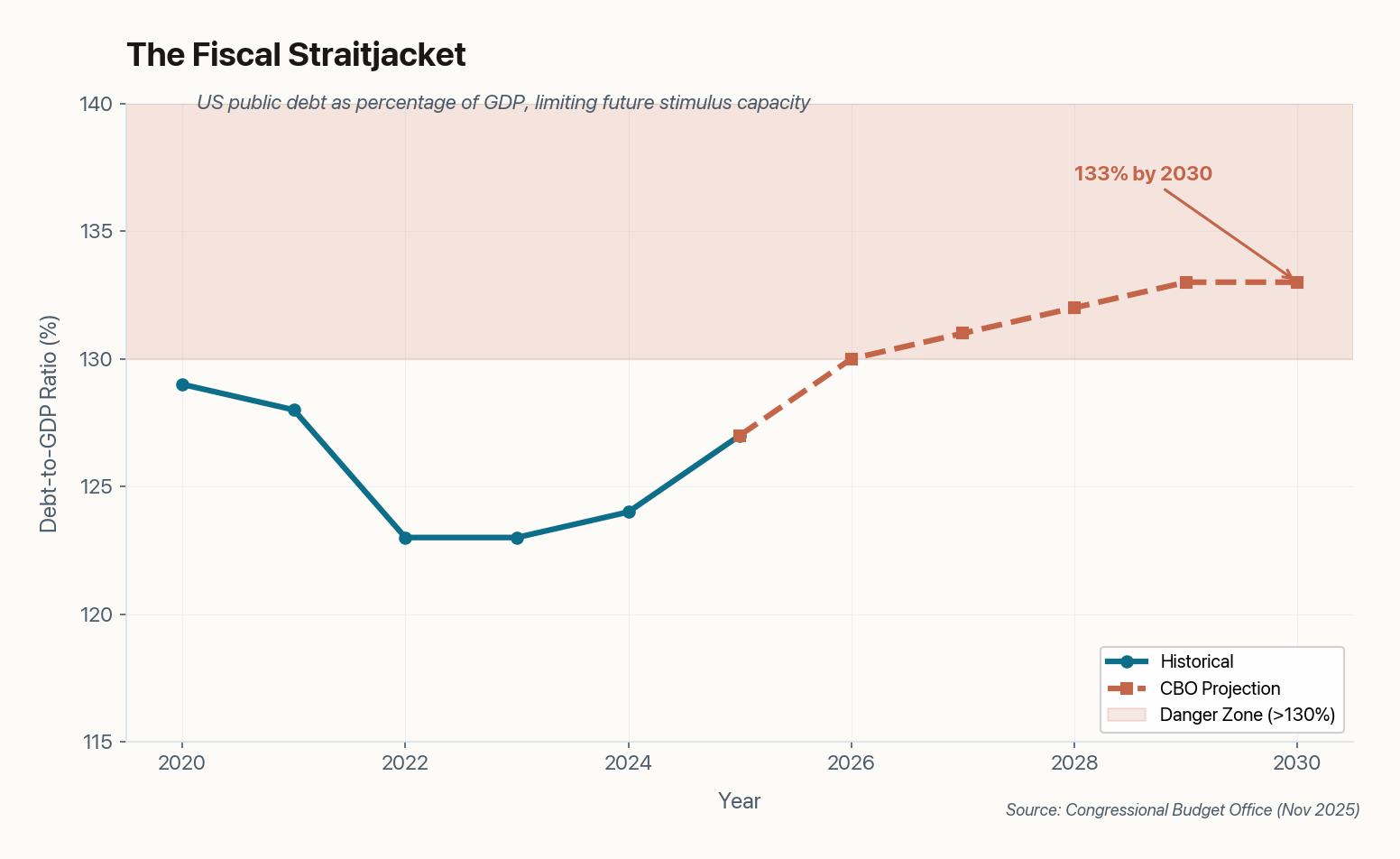

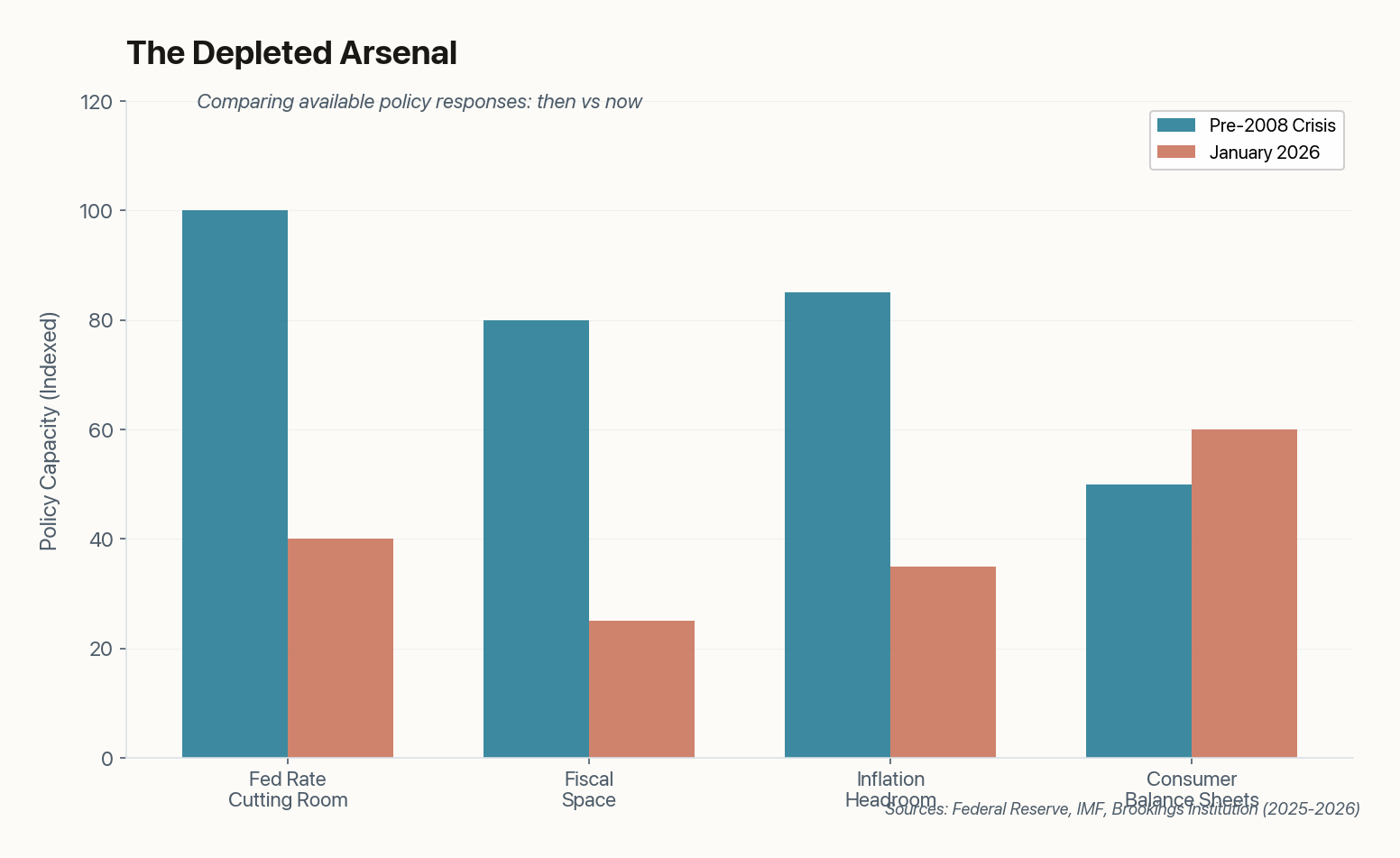

The steepening we're seeing in early 2026 isn't a sign of health—it's long-term yields staying stubbornly high because the Treasury keeps flooding the market with new debt. Translation: the bond market is betting that either inflation sticks around, or the government's credit risk is rising, or both. Neither interpretation suggests smooth sailing.