The Platform That Giveth, Taketh Away

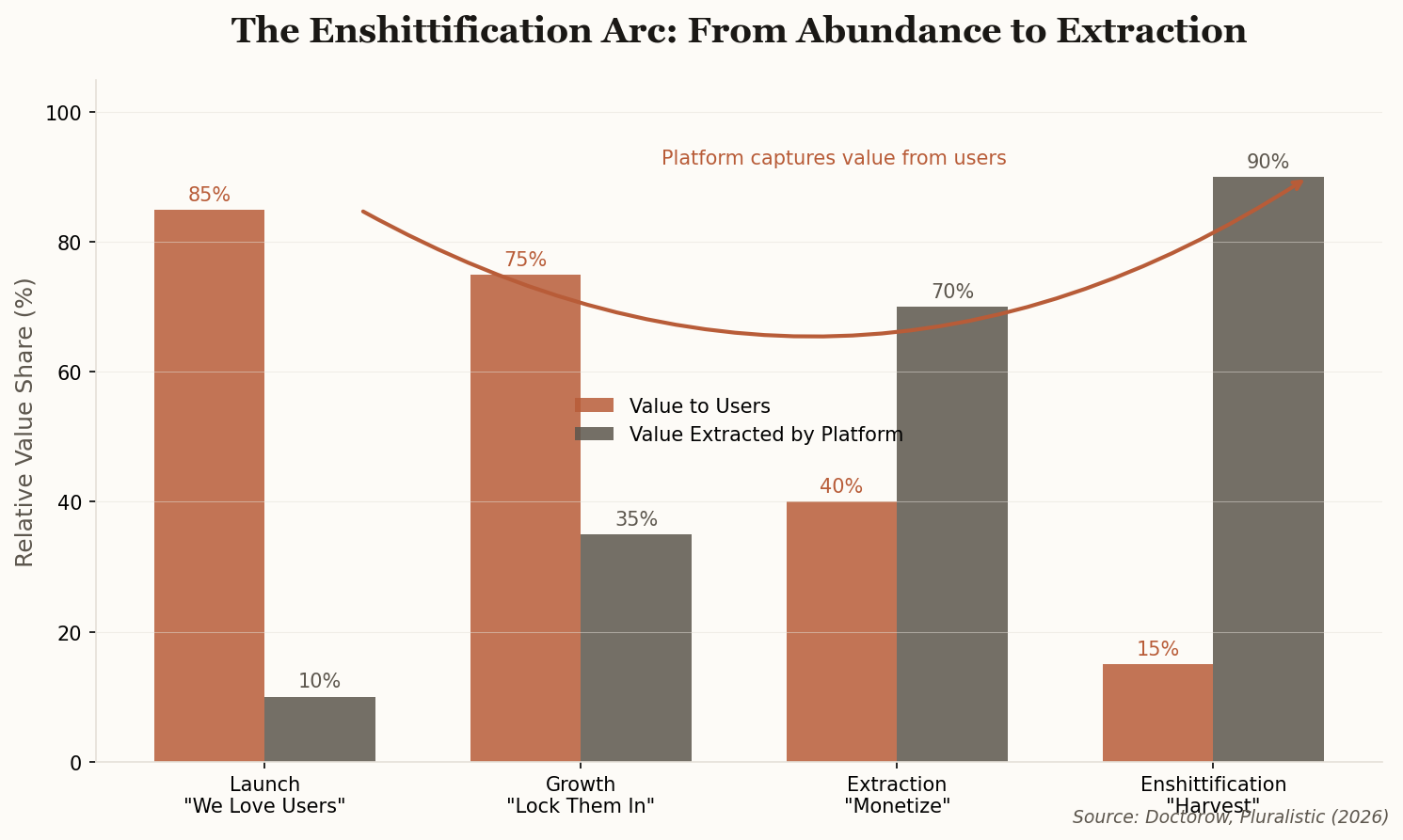

Cory Doctorow has been naming the beast for years, and in his latest essay, he finally drives the stake through the heart of the "abundance narrative." The pattern is now so predictable it should be a law of physics: platforms seduce users with generous abundance, lock them in with switching costs, then systematically extract value until the service becomes a hollow shell of its former self.

The tech industry calls this "growth." Doctorow calls it enshittification. The playbook runs like this: subsidize early users to build network effects, then—once escape becomes too costly—progressively degrade the experience while hiking prices and inserting ads. Facebook did it. Google did it. X is doing it in real-time.

The abundance ideologue sees infinite content, infinite connection, infinite convenience. What they miss is that manufactured abundance is a trap—the prelude to manufactured scarcity. The generous phase isn't charity; it's customer acquisition cost. And the bill always comes due.

"Enshittification is the process by which platforms die... first they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves." — Doctorow