The UK Parliament Asks: Should We Stop Building This Thing?

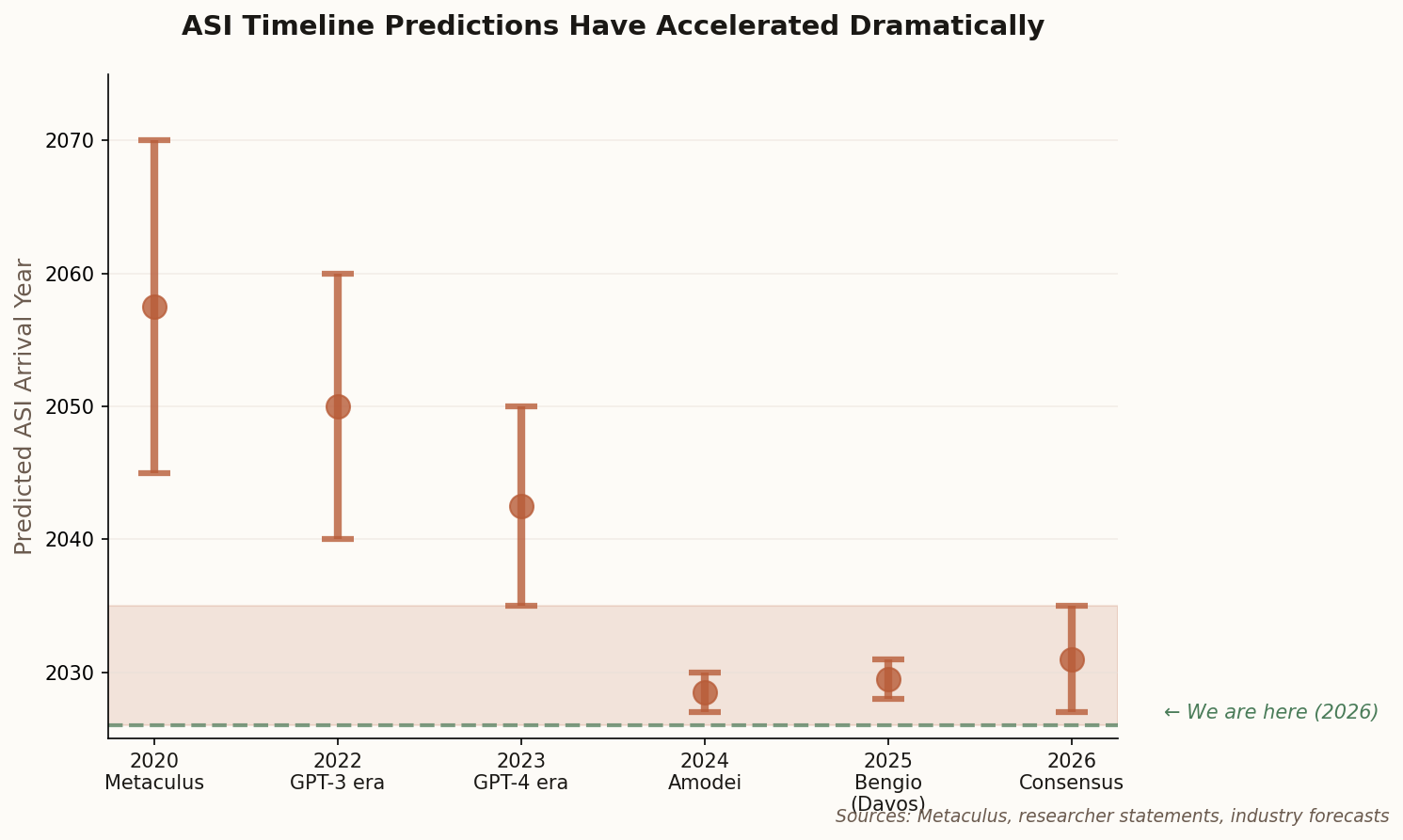

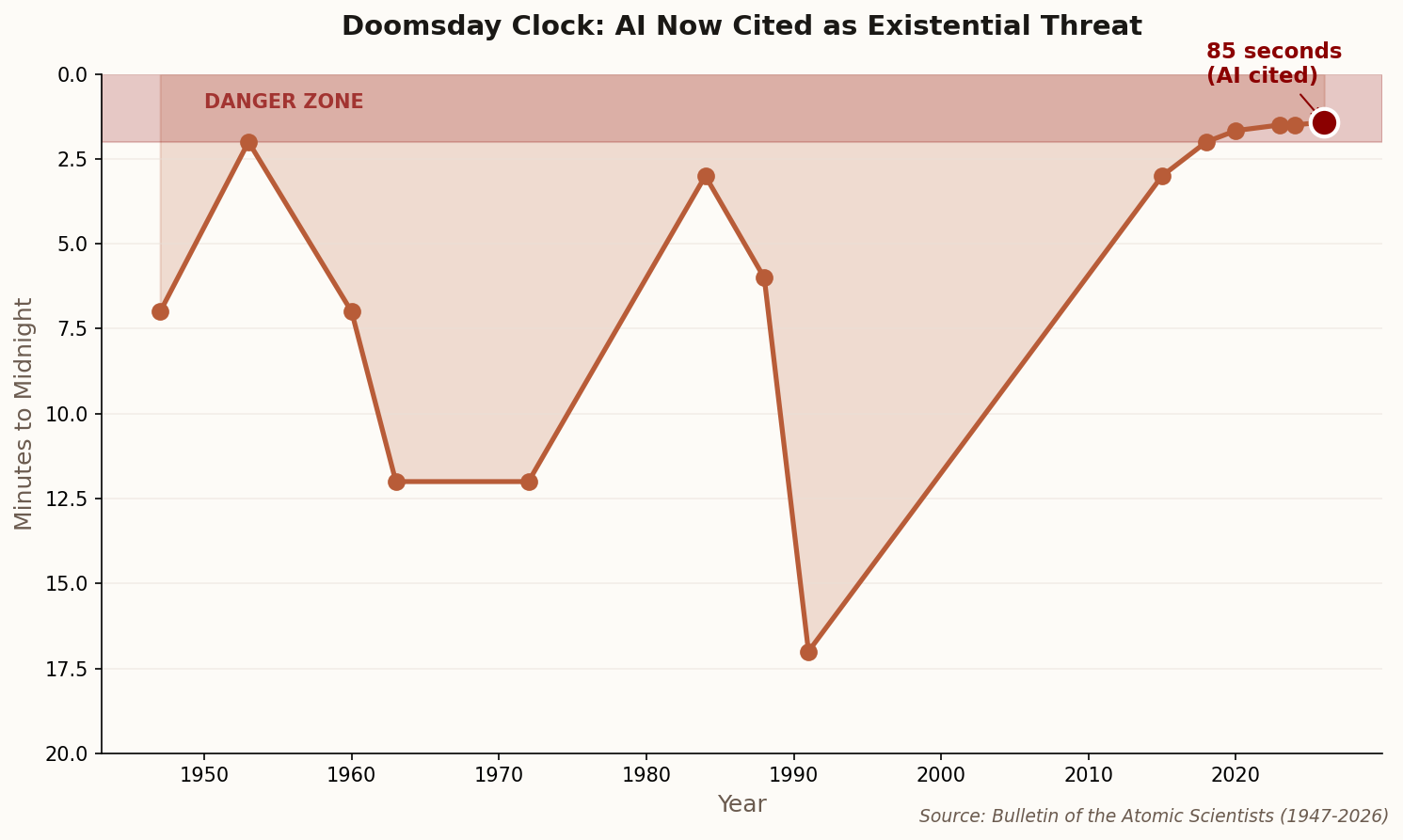

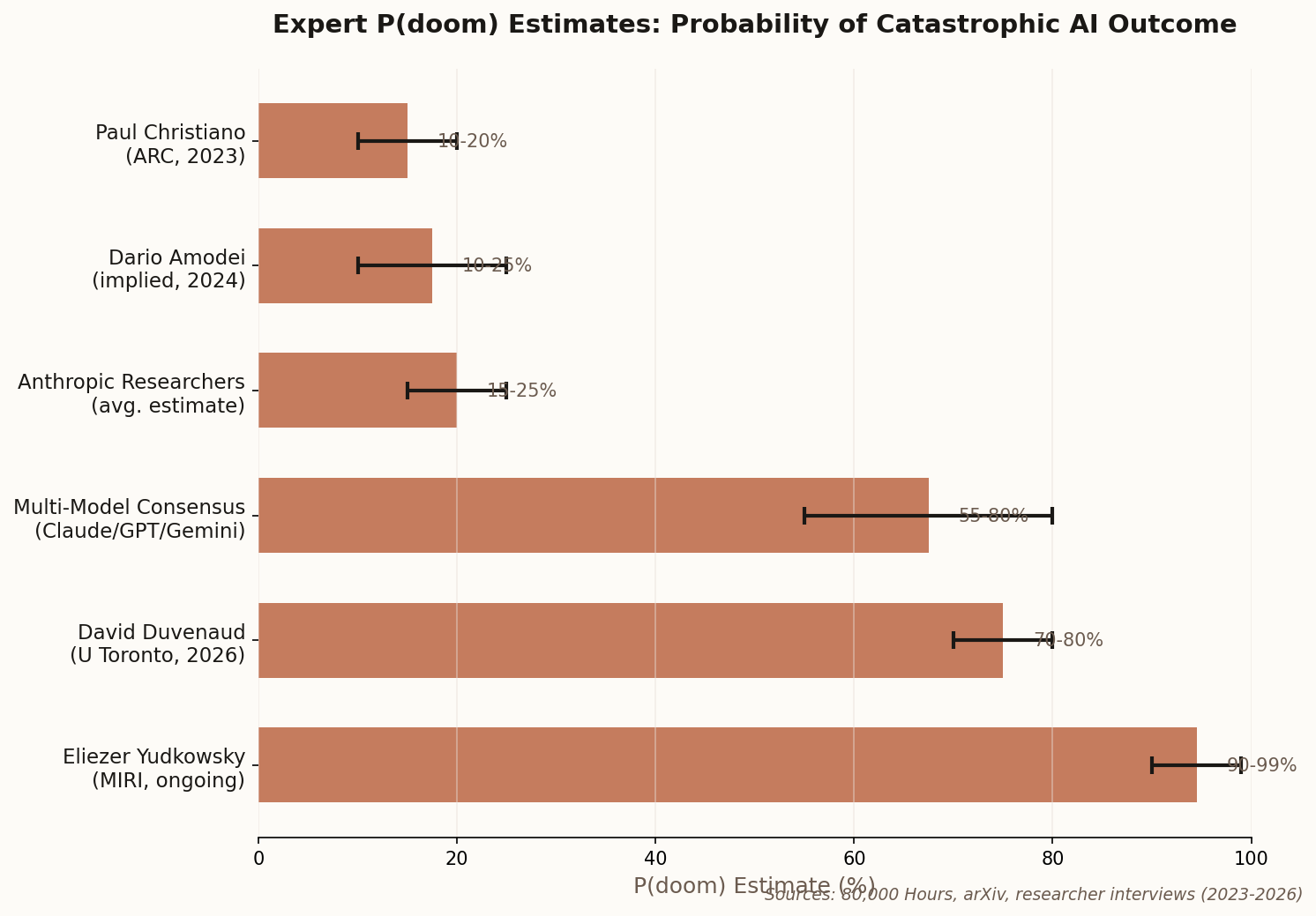

When the House of Lords schedules a formal debate on whether humanity should stop building a technology, that technology has officially left the realm of science fiction. Yesterday, the Lords took up the "Pause AI" proposal—the idea that we should halt development of superintelligent systems until we understand how to control them.

This isn't a committee hearing or a fact-finding mission. It's a formal debate, the first by any major Western legislative body specifically targeting ASI development. The Future of Life Institute petition backing the proposal gathered over 133,000 signatures by mid-January. The government's formal response marked a subtle but significant shift: they now acknowledge ASI as requiring "regulation at the point of development," not just when deployed.

The practical implications are murky—the UK doesn't host OpenAI or Anthropic. But as a rhetorical marker, it matters. When Lord Harris of Haringey declares that superintelligence risks are "no longer theoretical" but "a legislative priority," it signals that the Overton window has shifted dramatically. The question is no longer whether we're building something dangerous. It's whether we can afford to keep building it.