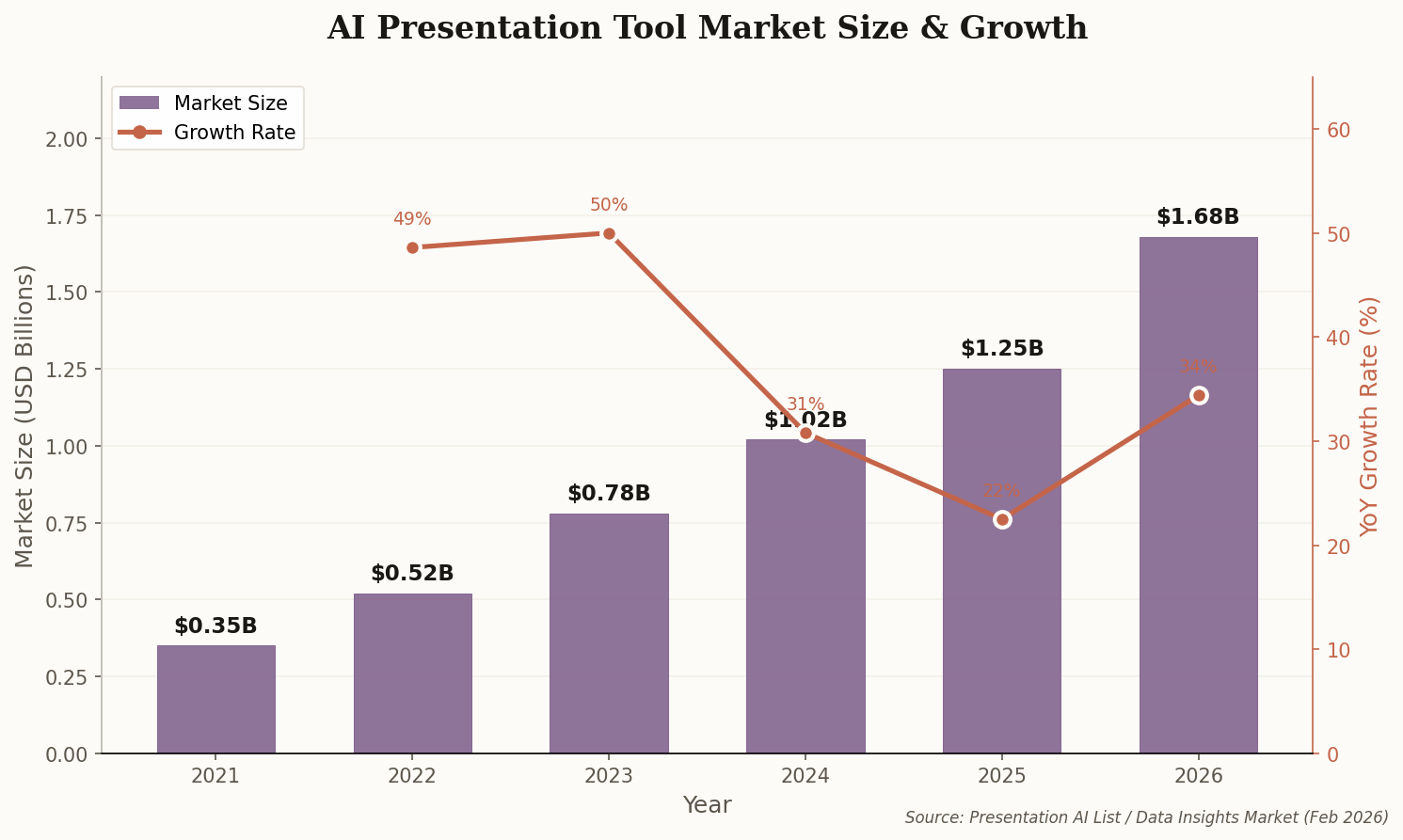

The $610 Million Question

Walk into any Barnes & Noble today and you'll find something curious: the biggest section isn't "Science Fiction" or "Fantasy" separately. It's the merged blob labeled "Sci-Fi/Fantasy"—and increasingly, a third creature lurks within: Romantasy.

In 2024, the "Romantasy" subgenre alone generated approximately $610 million in sales, driving a jaw-dropping 41.3% growth in the overall SFF category compared to the previous year. Rebecca Yarros's Fourth Wing didn't just sell books—it created a gravitational field that bent the entire shelving strategy of physical bookstores.

But here's what's fascinating: the merger of SF and Fantasy isn't new. BookTok didn't invent it. BookTok just revealed what booksellers have known since the 1960s—these readers were never separate populations to begin with.