Five Extra Minutes Changes Everything

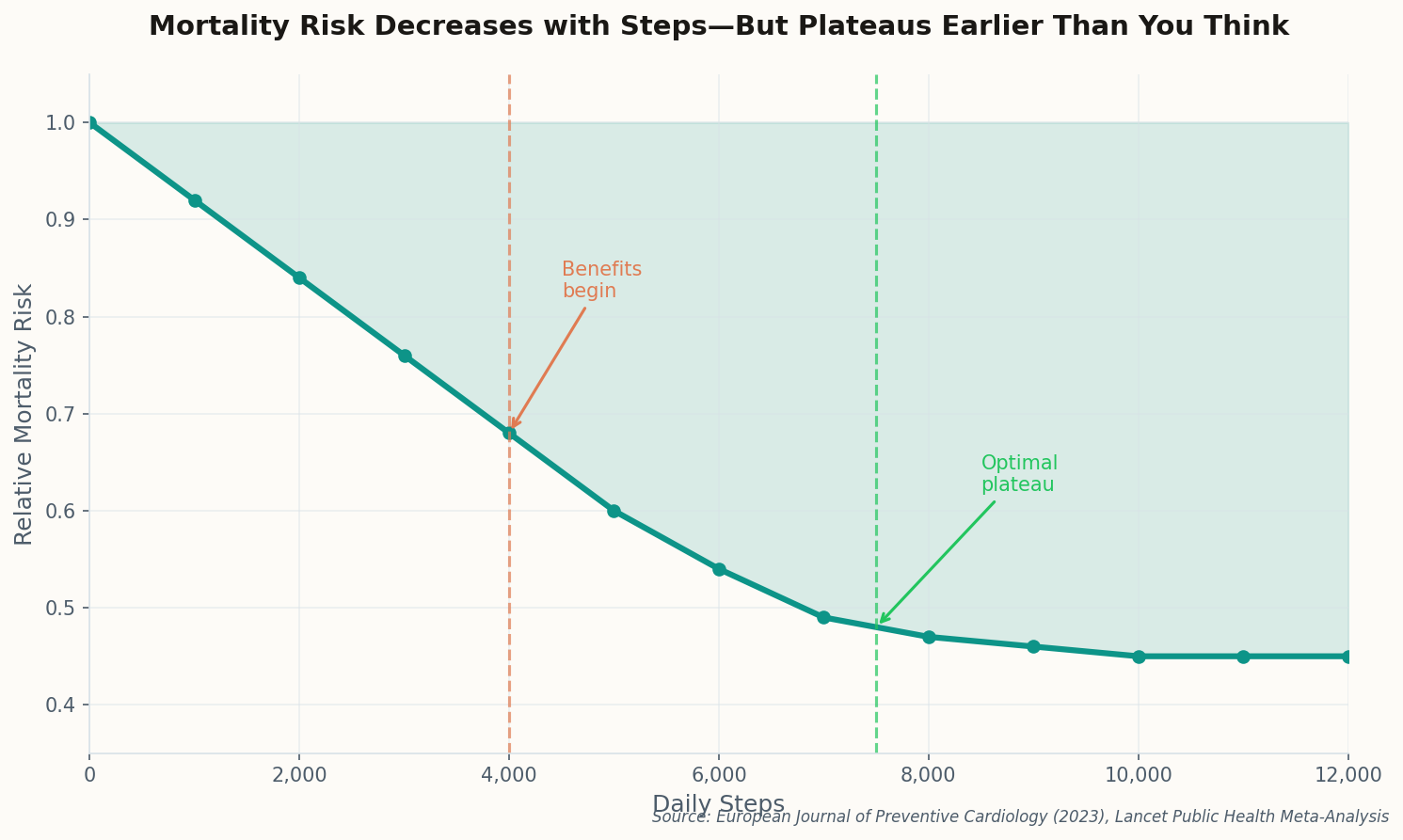

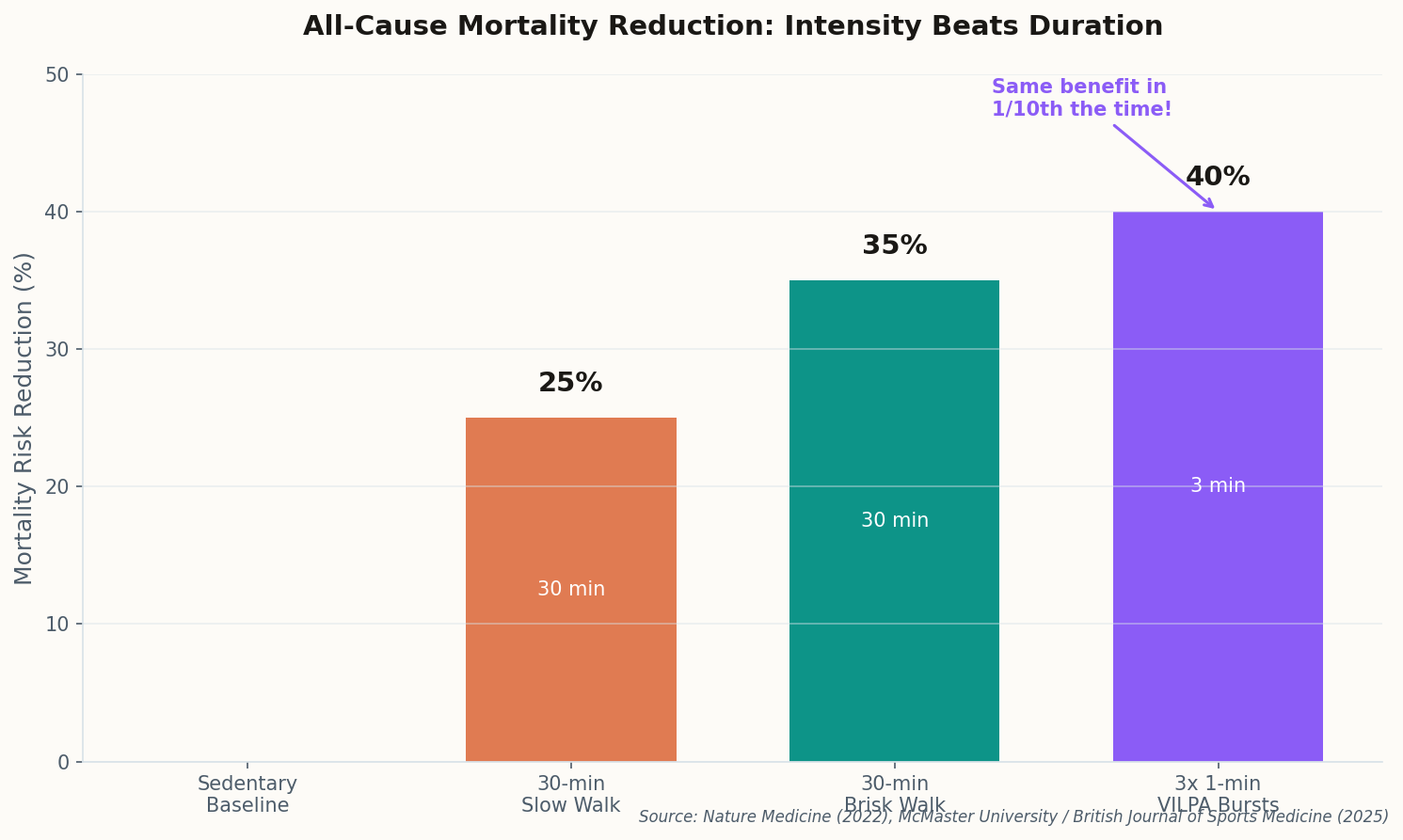

Here's the headline that should reshape how you think about exercise: a University College London study of 135,000 adults found that adding just five extra minutes of moderate activity—like brisk walking—reduces blood pressure and cuts mortality risk by nearly 10%.

Not thirty minutes. Not an hour. Five minutes.

The study also found that swapping 30 minutes of sitting for standing, sleeping, or walking showed measurable cardiovascular benefits. This isn't about marathon training or CrossFit obsession. It's about what researchers call "micro-movements"—tiny interventions that stack up over time.

The implication is profound: the barrier to meaningful health improvement isn't finding an hour for the gym. It's taking the stairs instead of the elevator, walking to a colleague's desk instead of sending Slack, or parking at the far end of the lot. The returns on these small investments are surprisingly large.