Fifteen Years Dead, His Playbook Still Dominates

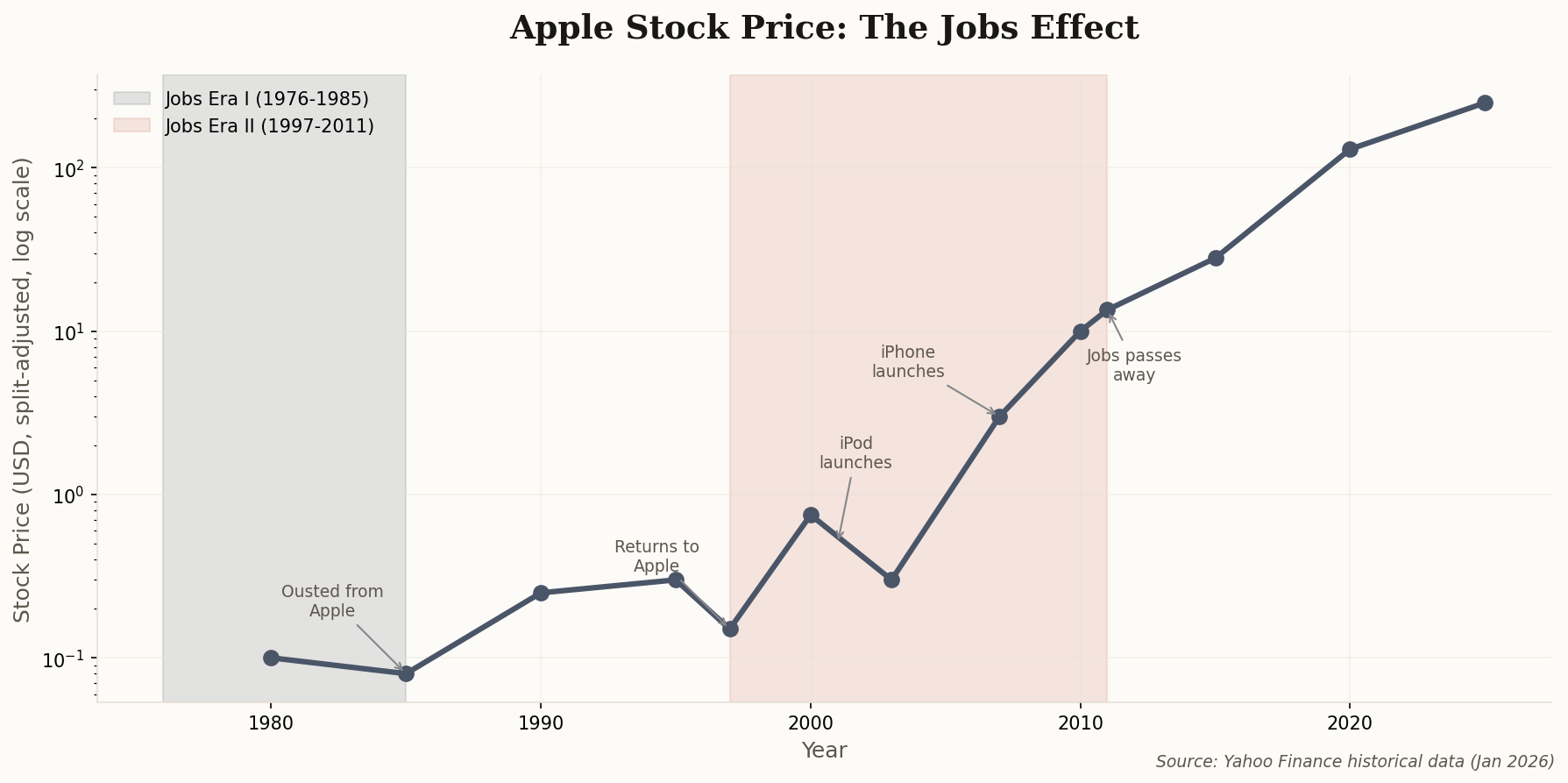

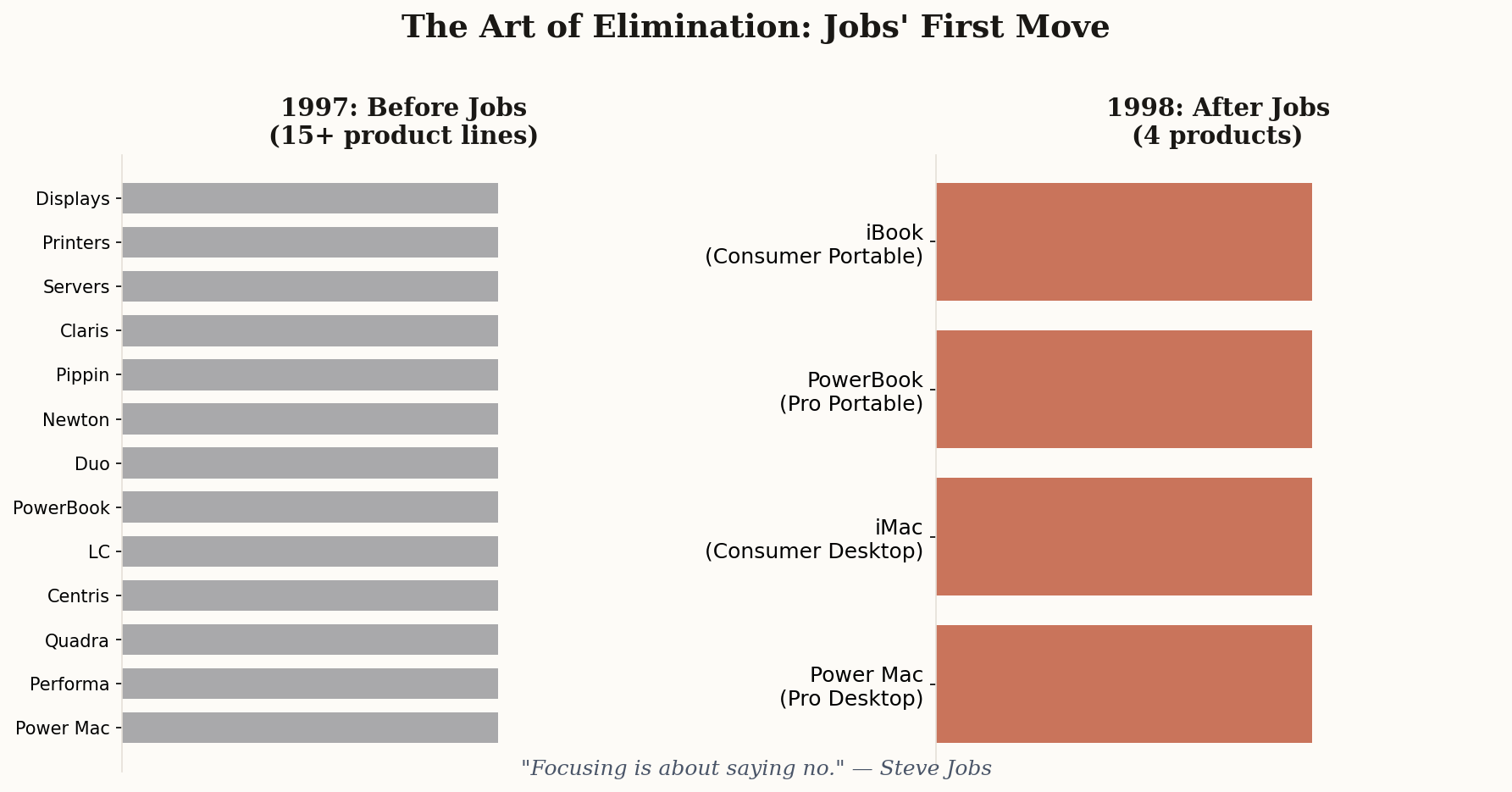

Here's the uncomfortable truth about Steve Jobs: in 2026, his operational tactics remain the gold standard for productivity advice. Cut 70% of your product line. Ban PowerPoint. Cap meetings at 30 minutes. "Focusing is about saying no." The man who made grown engineers cry is still the primary reference point for how to get things done.

This piece from Self-Manager catalogs ten specific Jobs tactics that modern productivity systems have adopted wholesale. The uncomfortable implication? Either his harsh methods genuinely produced superior results, or we're all cargo-culting a management style that happened to coincide with talent and timing.

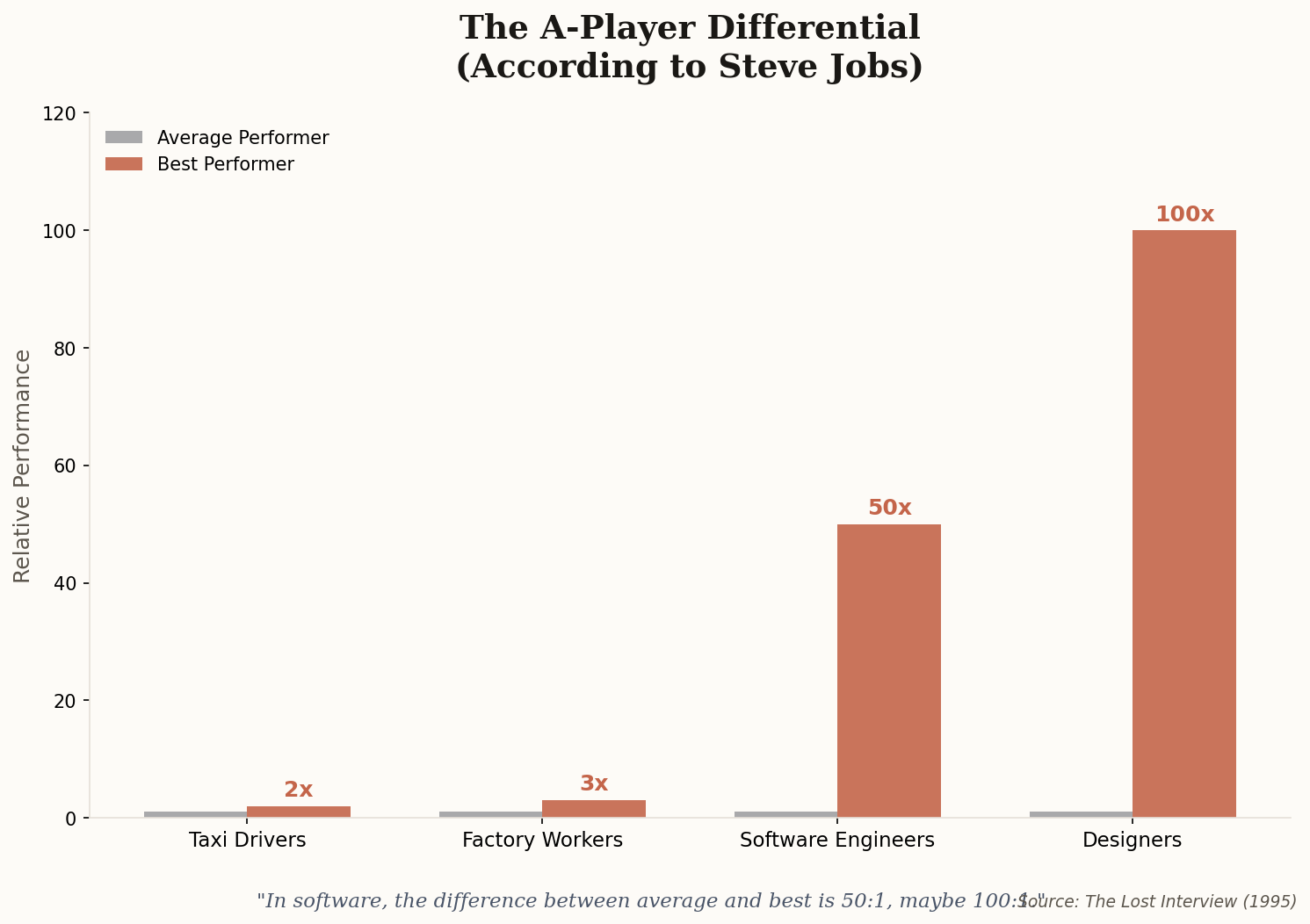

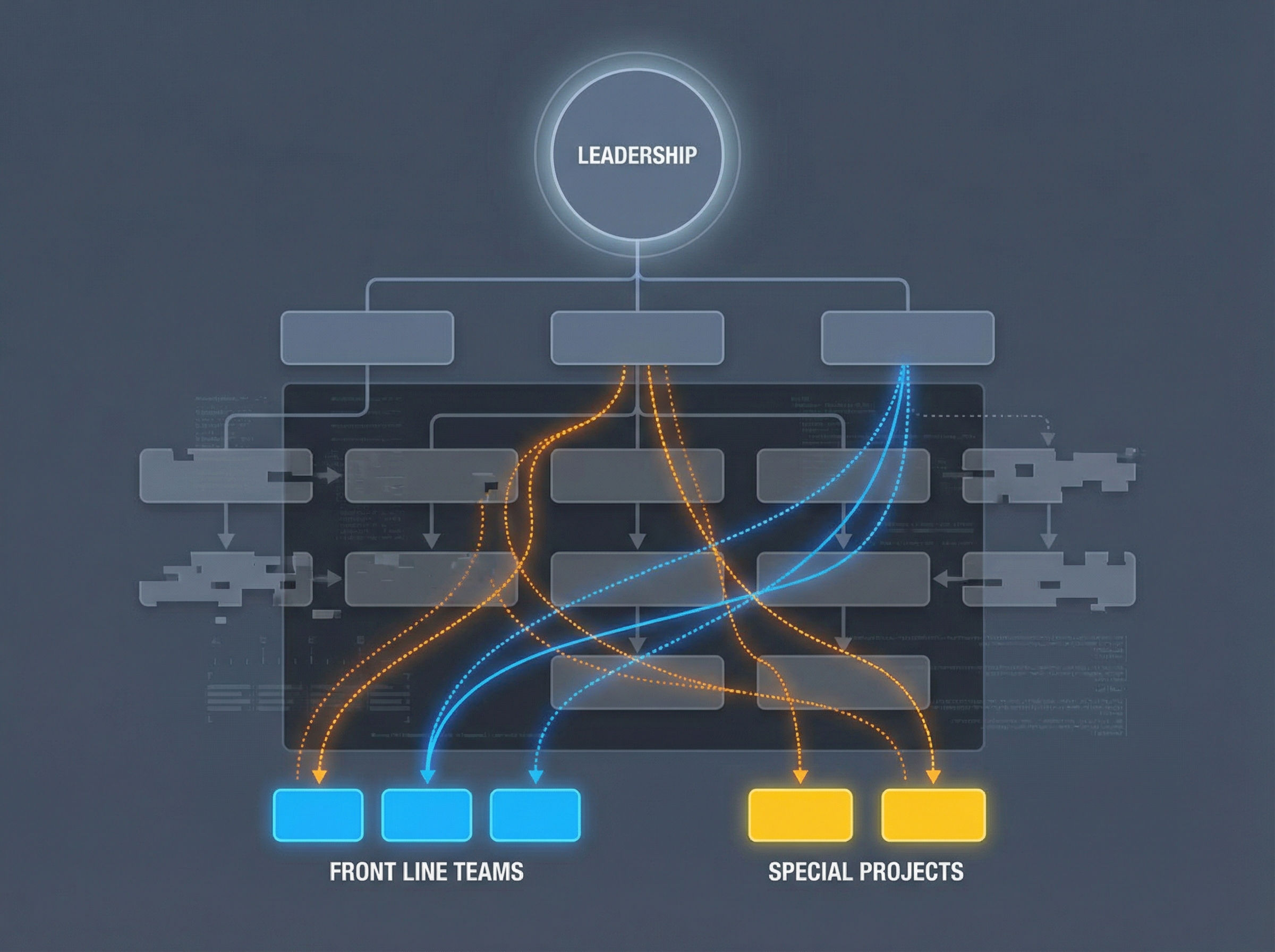

What strikes me is the specificity of the advice that survives. Not vague "think different" platitudes, but granular operational choices. No status update meetings. Whiteboard debates instead of slideshows. The A-team works on fewer things with total ownership. These weren't personality quirks—they were deliberate system design. And they still outperform the alternatives.