Leica Admits the Look Can Be Simulated

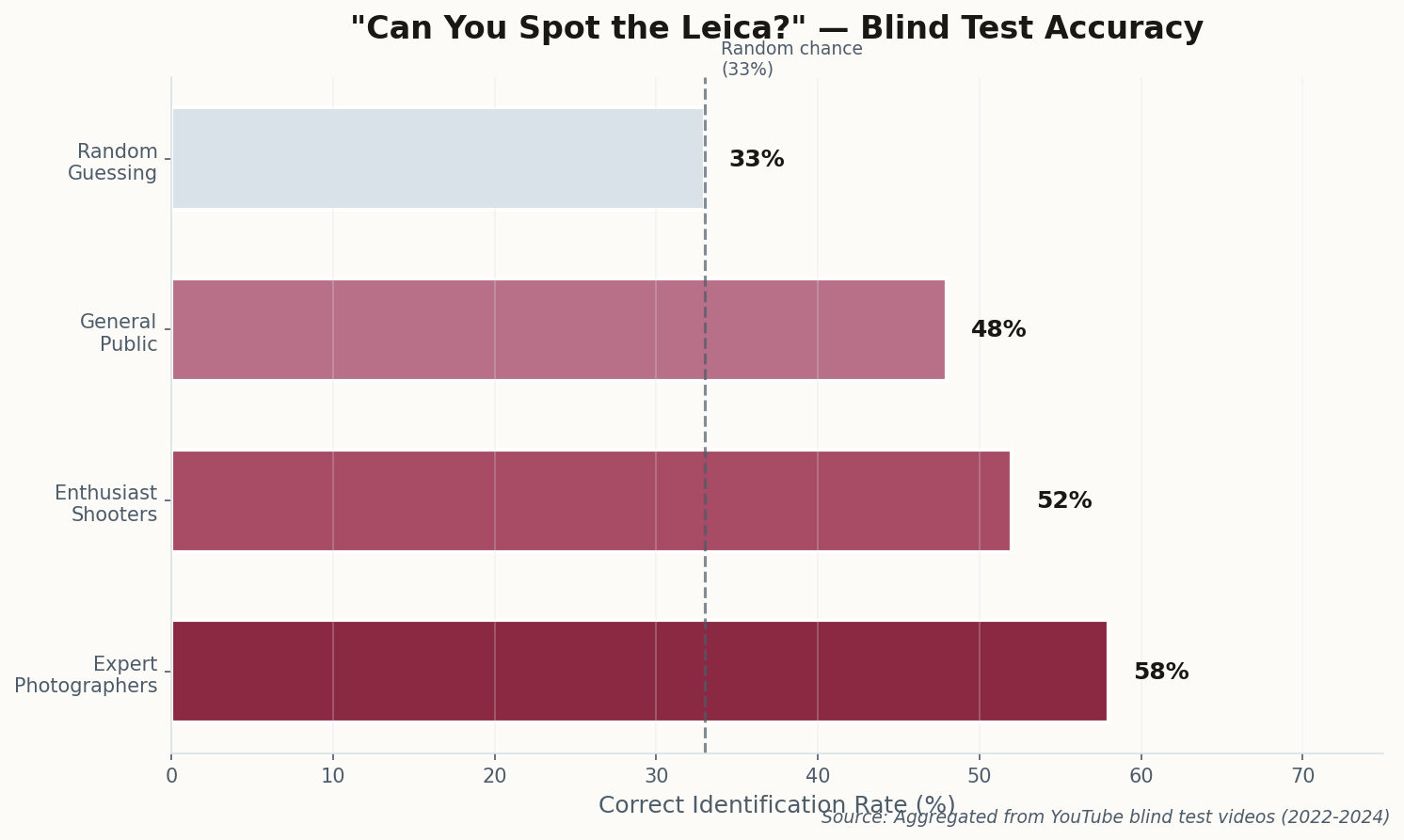

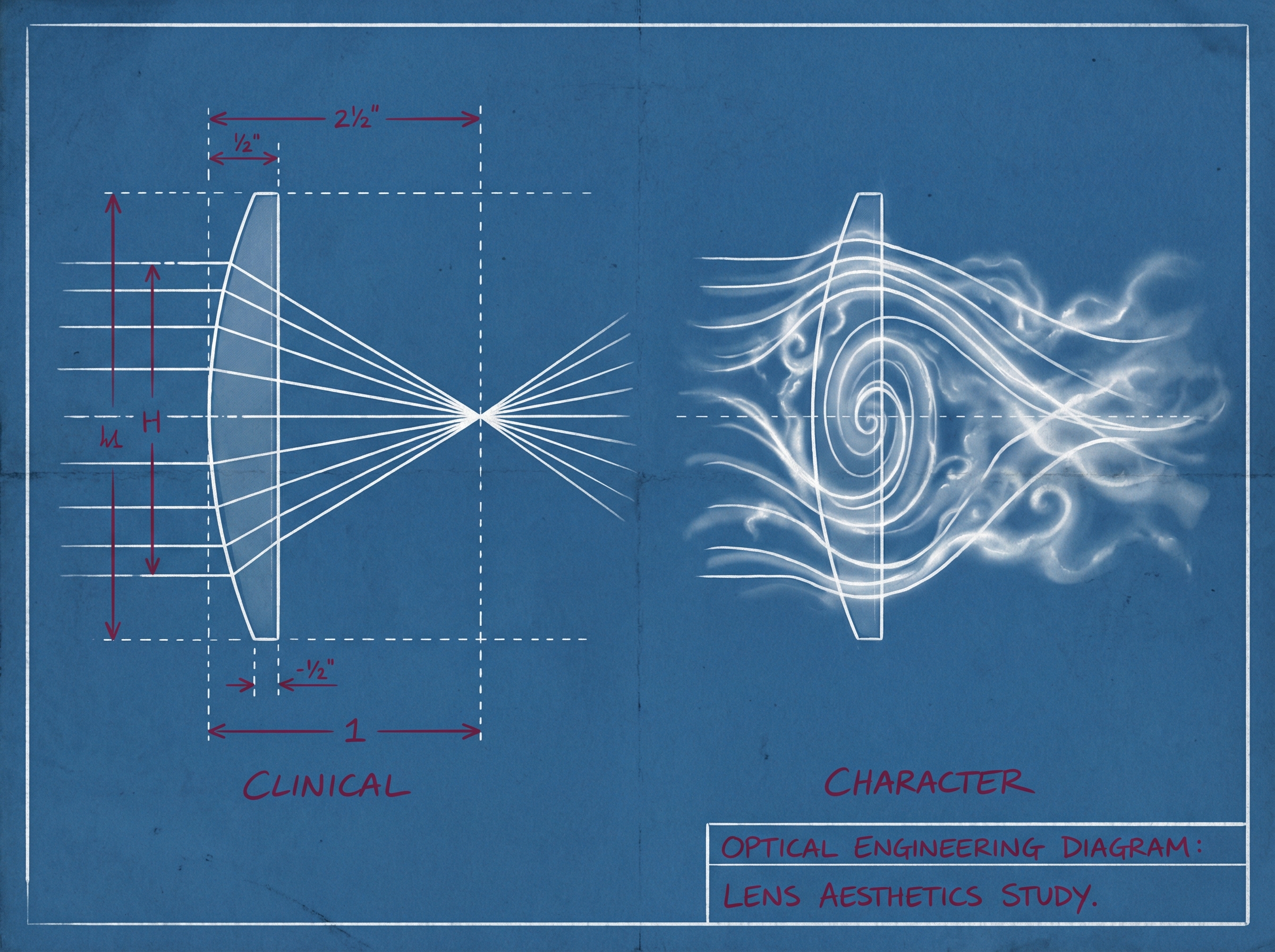

Here's the elephant in Wetzlar: Leica itself has quietly validated what skeptics have argued for years. The Leica LUX app, launched in mid-2024, uses machine learning to replicate the rendering characteristics of specific Leica lenses—including the legendary Noctilux-M 50mm f/1.2—on iPhone photos.

Read that again. The company whose entire premium positioning rests on irreplaceable optical DNA has released software that promises to approximate that DNA computationally. It's as if Patek Philippe launched an app that makes your Apple Watch feel like a Grand Complication.

"Utilizes machine learning to replicate the distinct 'Leica look' of various lenses on iPhones." — Leica official description

The implications are profound. If an algorithm can get you 90% of the way to "the look," what exactly are you paying $10,000 for? The answer increasingly appears to be: the experience of shooting with a Leica, not the irreproducible output. That's not nothing—but it's a very different value proposition than "only our glass can render light this way."