The Fever Dream: When Everyone Was a Genius

Here's the myth: America was prosperous in the 1920s, and then the stock market crashed and ruined everything. Here's the reality: the Roaring Twenties were already rotting from the inside.

New research from the Hoover Institution and UCLA Economics uses a three-sector general equilibrium model to show that labor, investment, and output were already significantly depressed relative to theoretical predictions well before Black Thursday. The "Roaring Twenties" narrative, it turns out, masks a structural break in the economy that made collapse not just possible but probable.

The speculative mania layered on top of this weakness was breathtaking. By 1929, margin buying had become a national sport. You could purchase $10,000 worth of stock with just $1,000 down. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had roughly doubled between 1927 and its September 1929 peak of 381. Shoe-shine boys gave stock tips. Joseph Kennedy famously said he knew it was time to get out when his shoe-shine boy started offering stock advice.

"The genesis of the Great Depression might lie in the 1920s economy... reflecting substantial changes in business organization that reduced demand for labor." — Hoover Institution, 2024

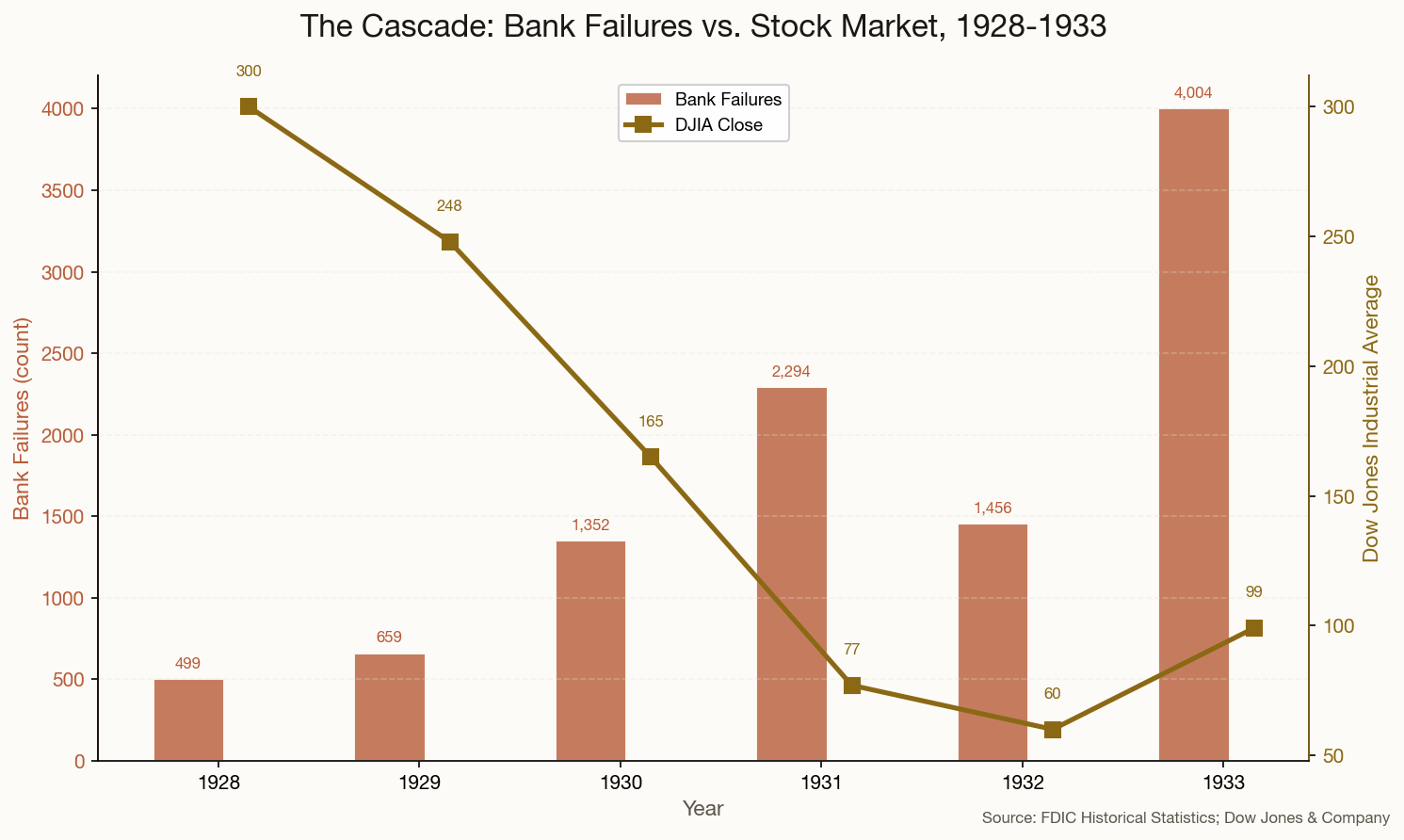

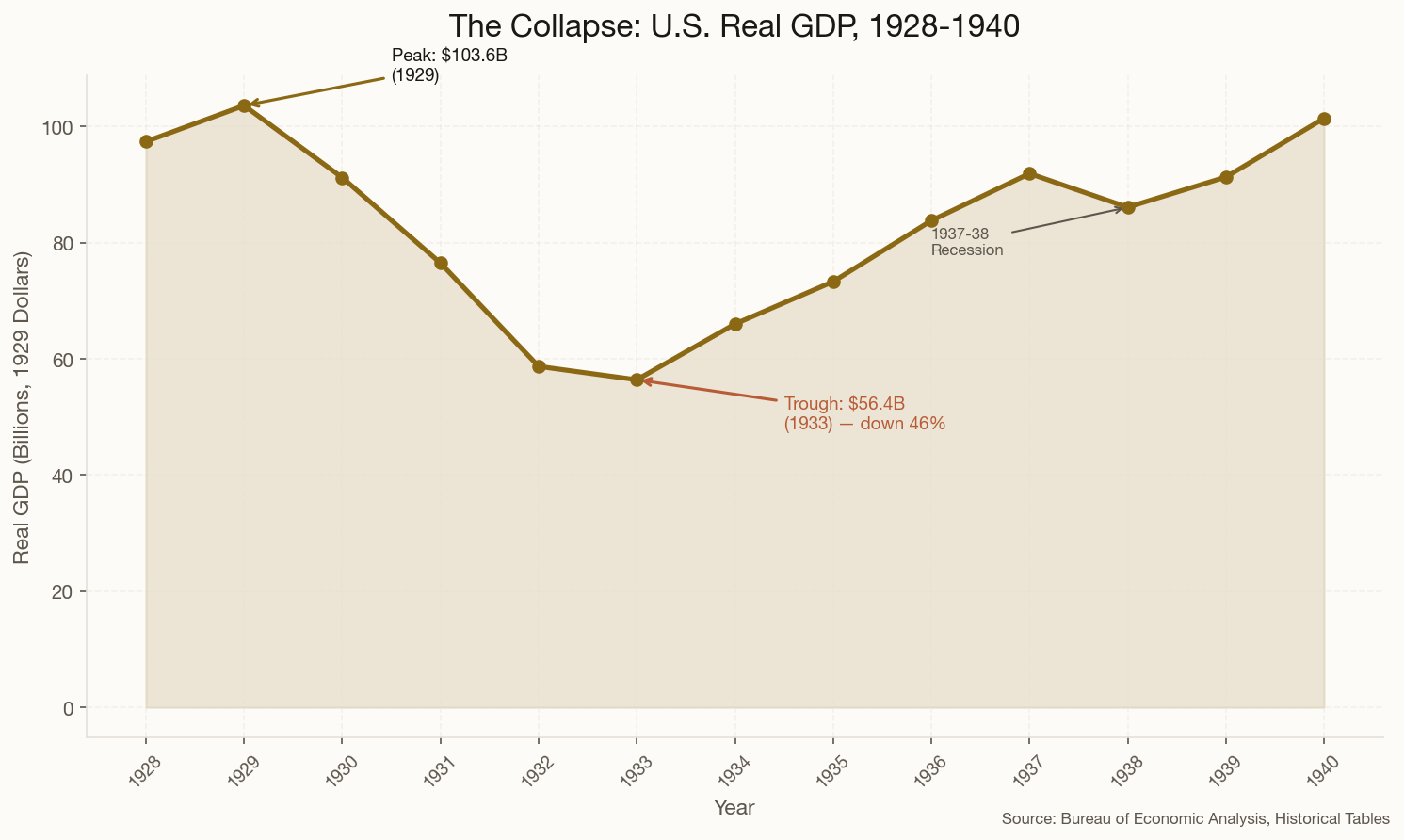

Then came Black Thursday (October 24, 1929) and Black Tuesday (October 29). The Dow would eventually lose 89% of its peak value, bottoming at 41.22 in July 1932. But the crash didn't cause the Depression — it detonated structural explosives that were already wired throughout the economy. The speculation merely determined the timing and the violence of the initial shock.