The Parade That Killed a City

On the morning of September 28, 1918, Philadelphia's public health director Dr. Wilmer Krusen faced one of history's most consequential judgment calls. Influenza was already circulating in the city. Navy doctors at the Philadelphia Navy Yard had warned him. And 200,000 people were about to line Broad Street for the Liberty Loans Parade — the largest parade in the city's history.

He let it proceed. Patriotic duty, he reasoned, outweighed unconfirmed risk.

Within 72 hours, every bed in Philadelphia's 31 hospitals was full. Within one week, 2,600 were dead. By the end of October, more than 12,000 Philadelphians had perished. Morgues overflowed. Bodies were stacked on porches because families had nowhere to put them. Priests drove horse-drawn carts through neighborhoods, calling for the dead like medieval plague collectors. The city dug mass graves with steam shovels.

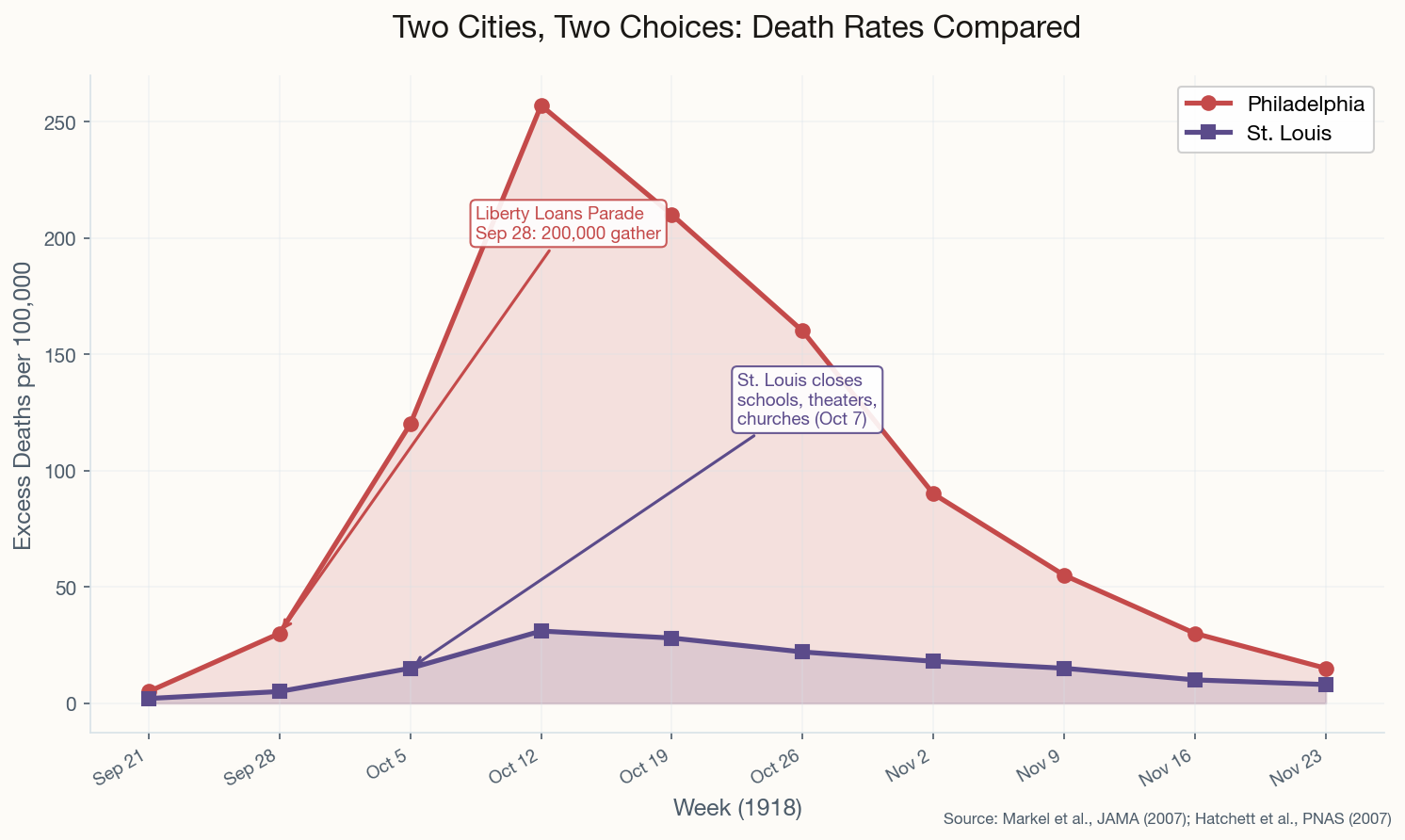

Philadelphia's peak death rate hit 257 per 100,000 per week. Compare that to St. Louis, where health commissioner Dr. Max Starkloff closed schools, theaters, and churches within two days of the first civilian cases. St. Louis peaked at 31 per 100,000 — roughly one-eighth of Philadelphia.

This wasn't a tragedy of ignorance. It was a tragedy of priorities. Krusen had the information. He chose war bond sales over public health. A landmark 2007 study by Howard Markel et al. in JAMA later confirmed the pattern across 43 cities: early, sustained interventions saved lives. Period. This case study became the foundation for "flatten the curve" a century later during COVID-19. The lesson was always there. We just had to relearn it.