The Treaty Trap: How Six Nations Chained Themselves Together

Here is the paradox that still haunts international relations: every alliance formed to prevent war made war more likely. By 1907, Europe had organized itself into two armed camps so rigid that any bilateral dispute would automatically become a continental one. The architecture of "peace through strength" became the architecture of collective suicide.

On one side, the Triple Alliance — born from the Dual Alliance of 1879 between Germany and Austria-Hungary, expanded in 1882 to include Italy. On the other, the Triple Entente — stitched together from the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, the Entente Cordiale of 1904, and the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907. Each agreement was rational in isolation. Together, they formed a doomsday machine.

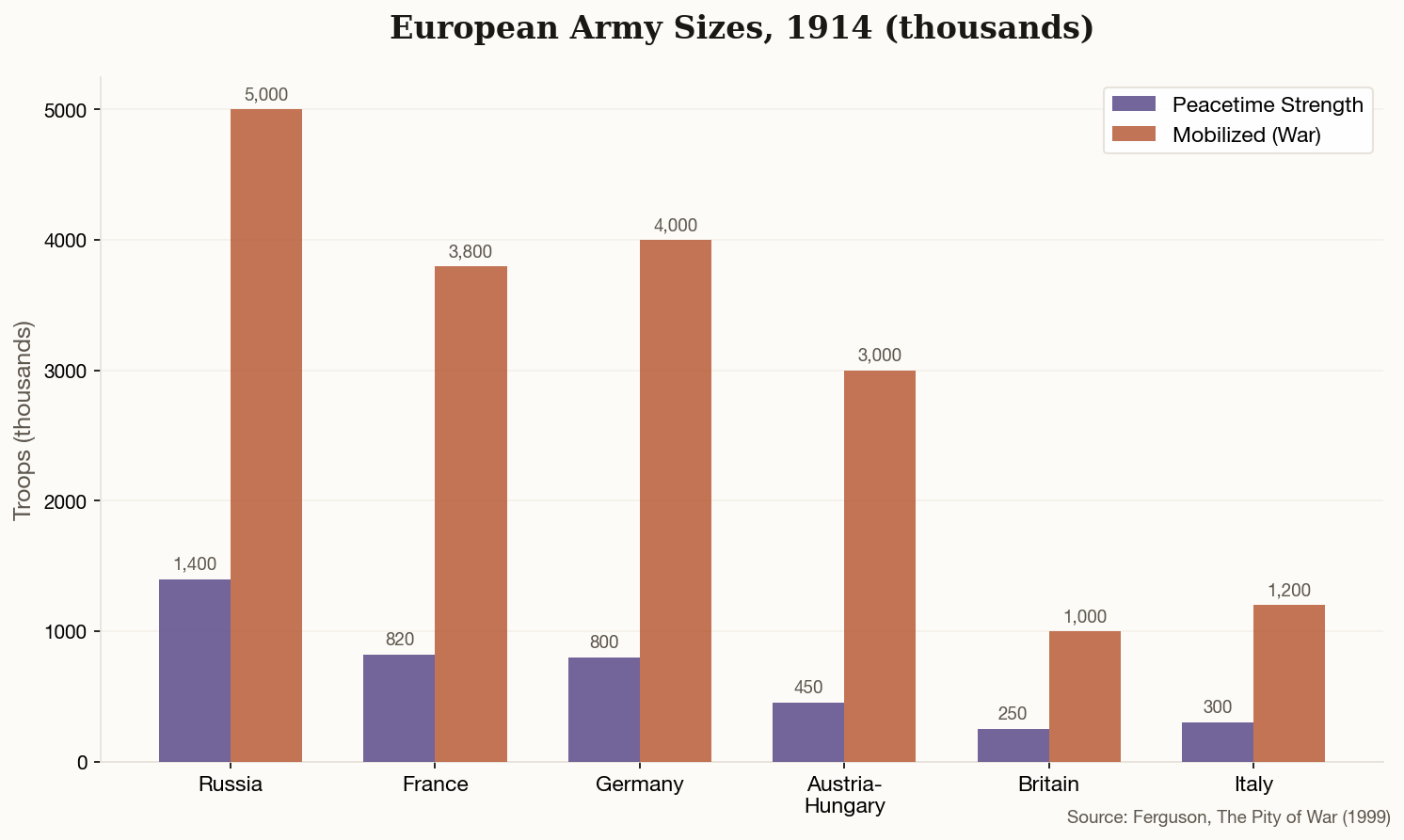

The Franco-Russian pact alone committed Russia to deploy 700,000–800,000 troops against Germany if France were attacked. That single clause meant a Balkan crisis involving Austria-Hungary would drag in Russia (Slavic solidarity), which would activate Germany (Dual Alliance), which would trigger France (Franco-Russian Alliance), which would pull in Britain (Entente Cordiale's informal military cooperation). No one designed this cascade. Everyone contributed to it.

The core lesson: Security guarantees don't just deter — they also entangle. Every treaty that made one country feel safer made the system as a whole more fragile. The alliance web didn't cause the war, but it guaranteed that any war would be enormous.