A Banker, an Engineer, and a Stationer Walk Into Hamburg

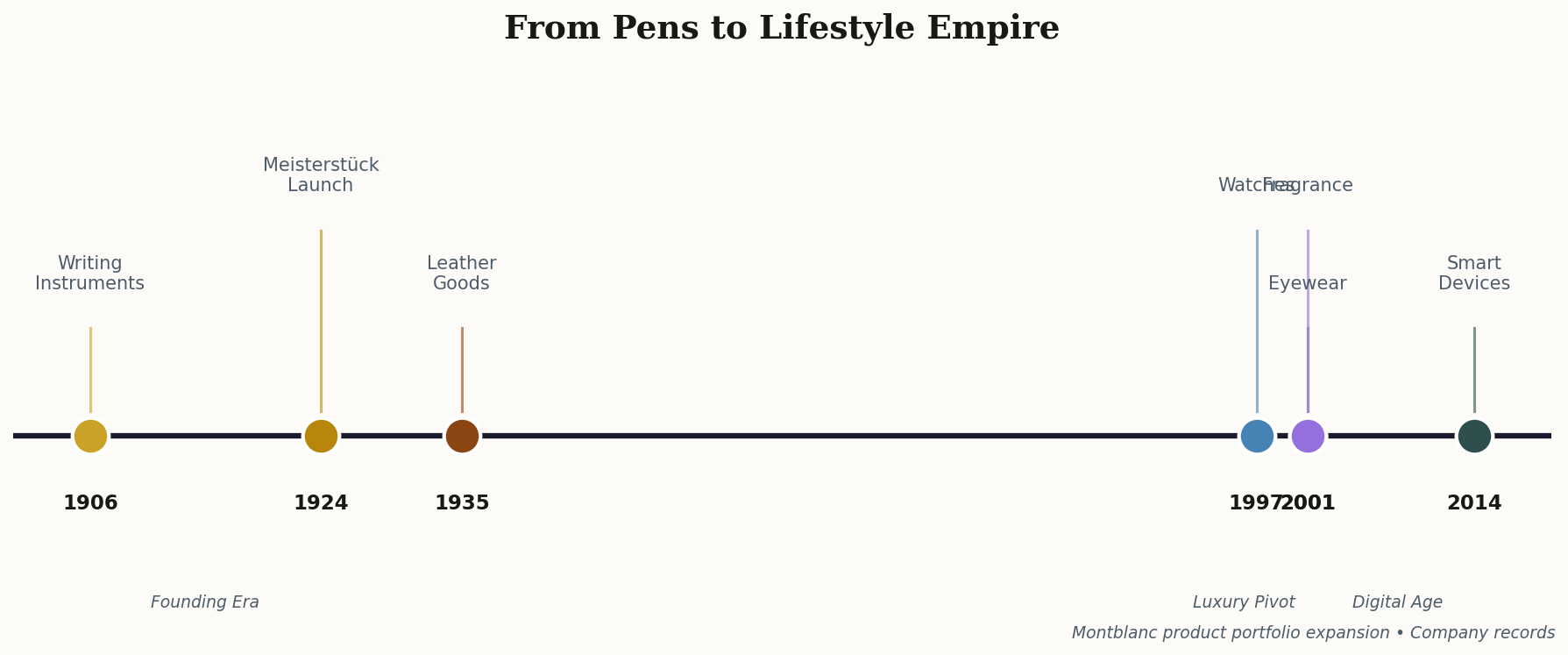

The year was 1906. In Hamburg, Germany, three men with distinctly different skill sets decided that writing instruments could be better. Alfred Nehemias brought money (he was a banker). August Eberstein brought engineering expertise. Claus Johannes Voss brought retail instinct as a stationer. Together, they founded what would become one of the most recognizable luxury brands on Earth.

They didn't call it Montblanc. Not yet. The company started as "Simplo Filler Pen Co." in 1907, after a brief stint under the unwieldy name "Simplizissiumus-Füllhalter." Their first breakthrough came in 1909 with the "Rouge et Noir"—a safety pen with a distinctive red cap that earned it the nickname "Little Red Riding Hood" in some markets. The name came from Stendhal's famous novel, a literary reference that hinted at the company's future positioning.

What made them different? At a time when fountain pens were either cheap and unreliable or expensive curiosities, Nehemias, Eberstein, and Voss aimed for the middle ground that would eventually become the high ground: pens that worked beautifully, felt substantial, and signaled something about their owners. The pen as status symbol was born not in a luxury goods boardroom but in a Hamburg workshop, among engineers who simply believed writing instruments deserved more respect.