Seven Workers and a Dead Man's Secret

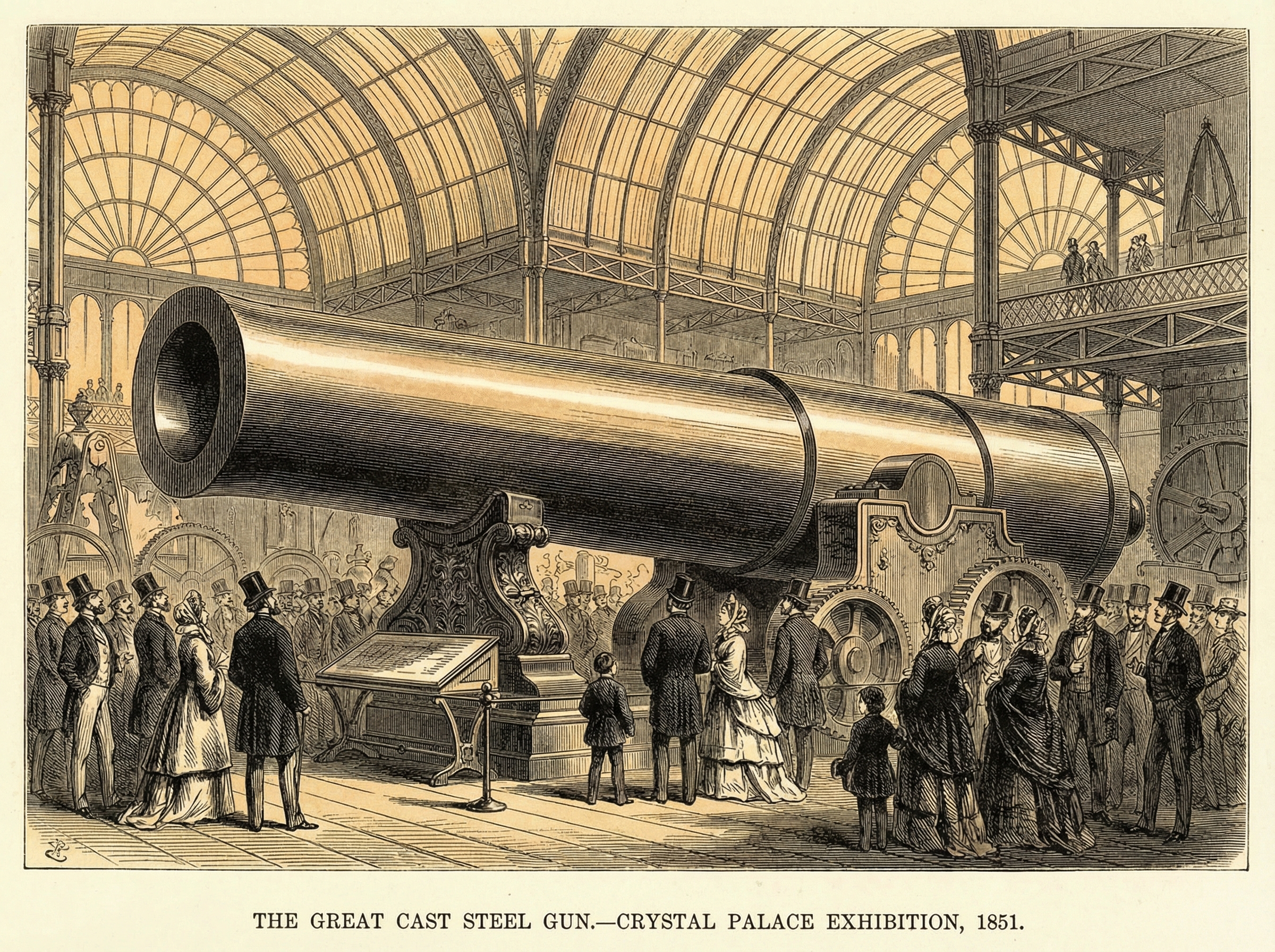

The Krupp family first appears in Essen's registry in 1587, when one Arndt Krupp made his fortune the old-fashioned way: buying up the property of neighbors who fled the plague. Capitalism has always rewarded the unsqueamish. But the industrial dynasty proper begins with Friedrich Krupp, a man consumed by a single obsession: cracking the English monopoly on cast steel.

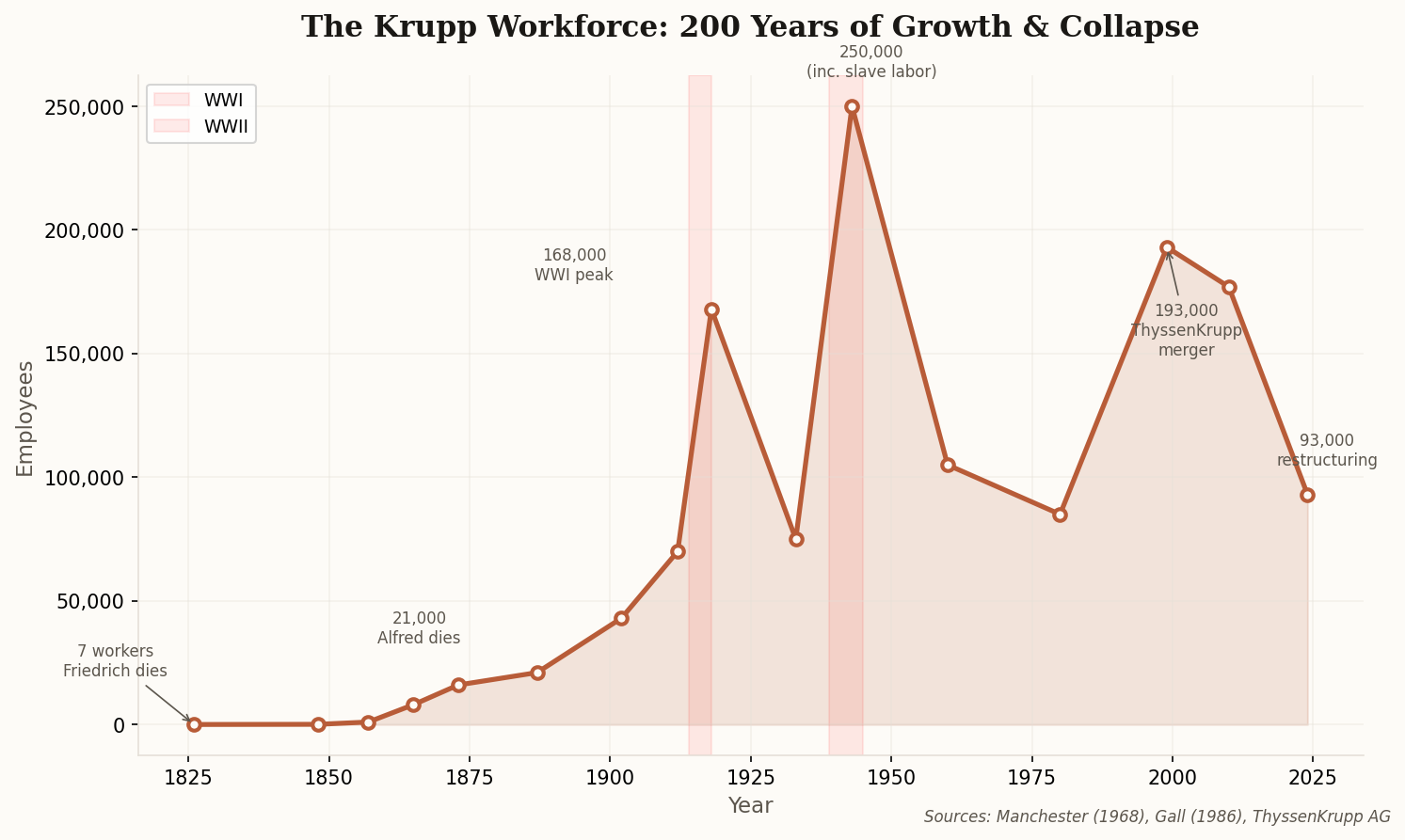

In 1811, Friedrich founded the Fried. Krupp Gussstahlfabrik—the Cast Steel Works. The name was grander than the reality. He burned through the family fortune trying to reverse-engineer what Sheffield foundries had perfected over generations. By the time tuberculosis killed him in 1826, the "factory" was a single workshop with seven employees and a mountain of debt. His 14-year-old son Alfred inherited the secret recipe for cast steel and absolutely nothing else.

That inheritance—a formula and a ruin—would become the seed of Europe's largest industrial empire. Every dynasty needs its founding myth, and the Krupps have one of the best: a dead father, a boy with a secret, and a forge still warm.