The Palace That Contains All Possible Symmetries

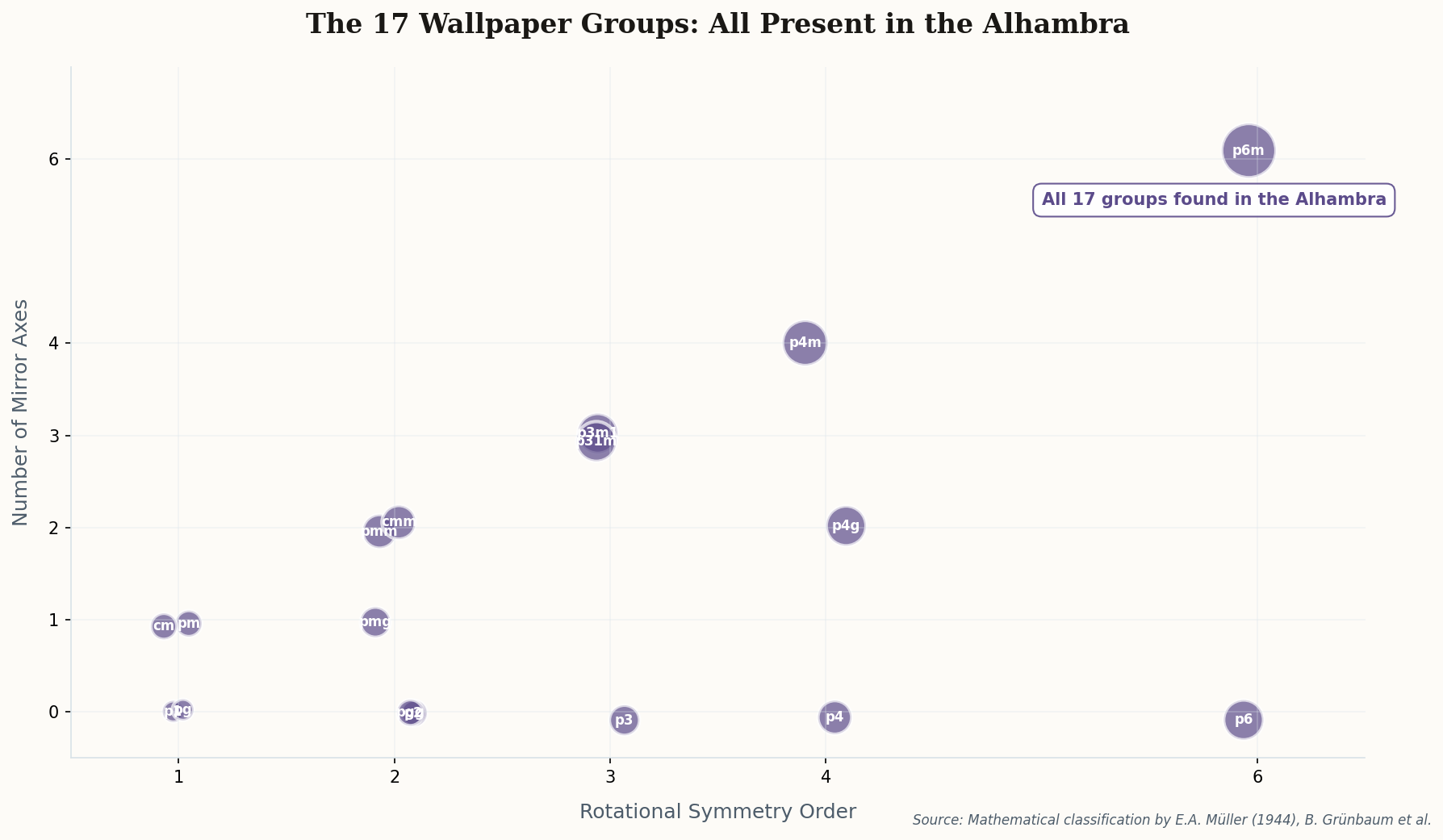

In 1944, mathematician Edith Müller sat down with photographs of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, and made a startling claim: this 14th-century palace contained examples of all 17 possible ways to tile a plane with repeating patterns. Every wallpaper group. Every symmetry operation. All of them, created six centuries before mathematicians had even proven that exactly 17 such groups exist.

The mathematics here isn't decorative—it's fundamental. A "wallpaper group" describes the symmetries of a pattern that repeats infinitely in two directions. You can rotate it, reflect it, glide it, or combine these operations in specific ways. The Russian crystallographer Evgraf Fedorov proved in 1891 that there are precisely 17 distinct combinations. The Nasrid artisans of the Alhambra found all 17 through pure visual intuition, compass, and straightedge.

Walk through the Hall of the Abencerrajes and you're walking through a textbook of mathematical group theory, rendered in ceramic and stucco. The muqarnas dome overhead—a honeycomb of interlocking cells—isn't just beautiful. It's a three-dimensional proof that these medieval craftsmen understood something profound about the structure of space itself.