Richard Pryor: The Man Who Made Confession an Art Form

Before Richard Pryor, stand-up comedy had rules. Don't talk about race. Don't talk about drugs. Don't talk about the parts of yourself you're ashamed of. Pryor burned those rules to the ground—sometimes literally, given the infamous freebasing incident he later turned into material.

What made Pryor revolutionary wasn't just his willingness to discuss taboo subjects. It was his refusal to perform a version of himself. When he talked about growing up in his grandmother's brothel in Peoria, about his MS diagnosis, about setting himself on fire while freebasing cocaine, he stripped away the protective irony that most comedians hide behind. He was raw in a way that made audiences uncomfortable—and then made them laugh anyway.

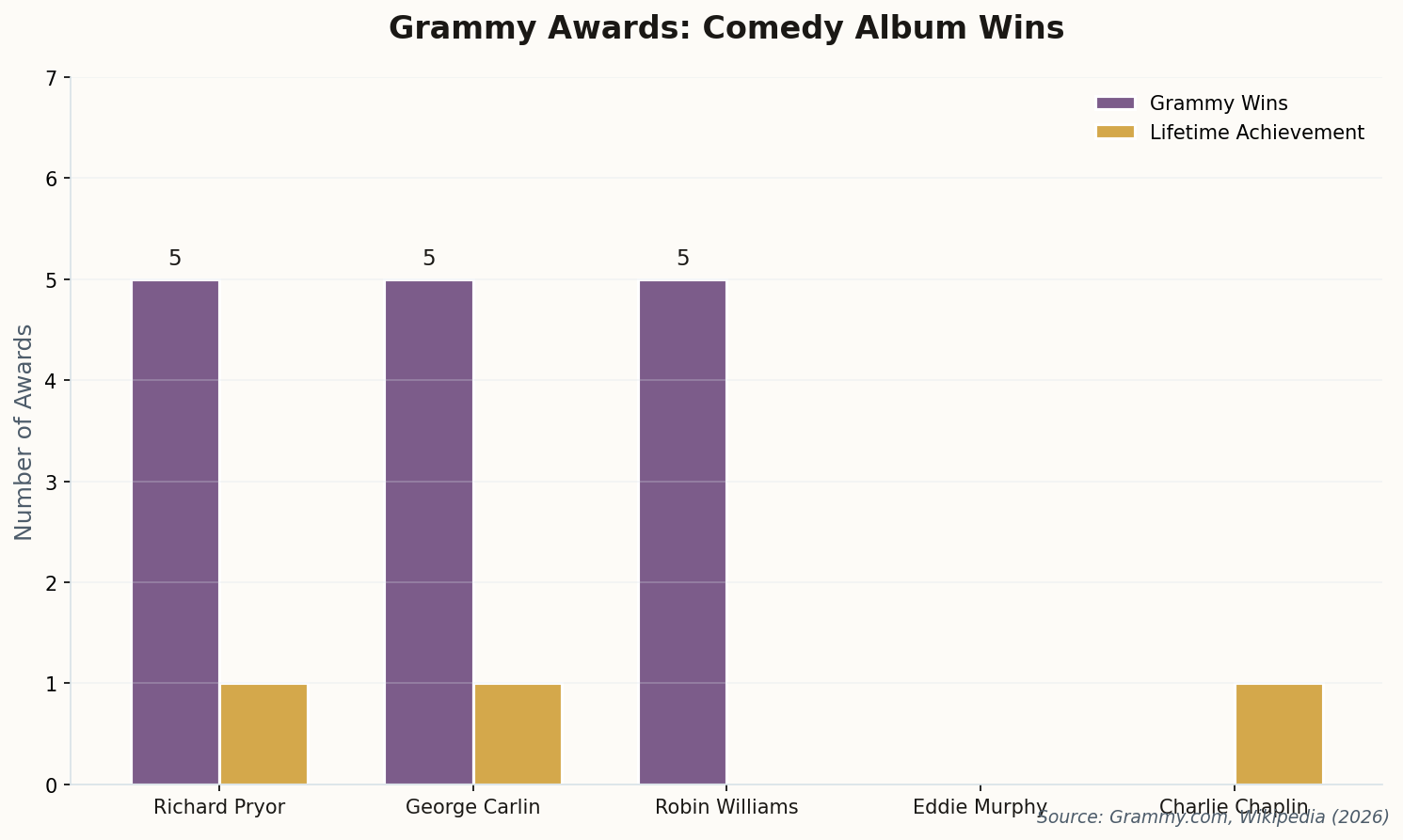

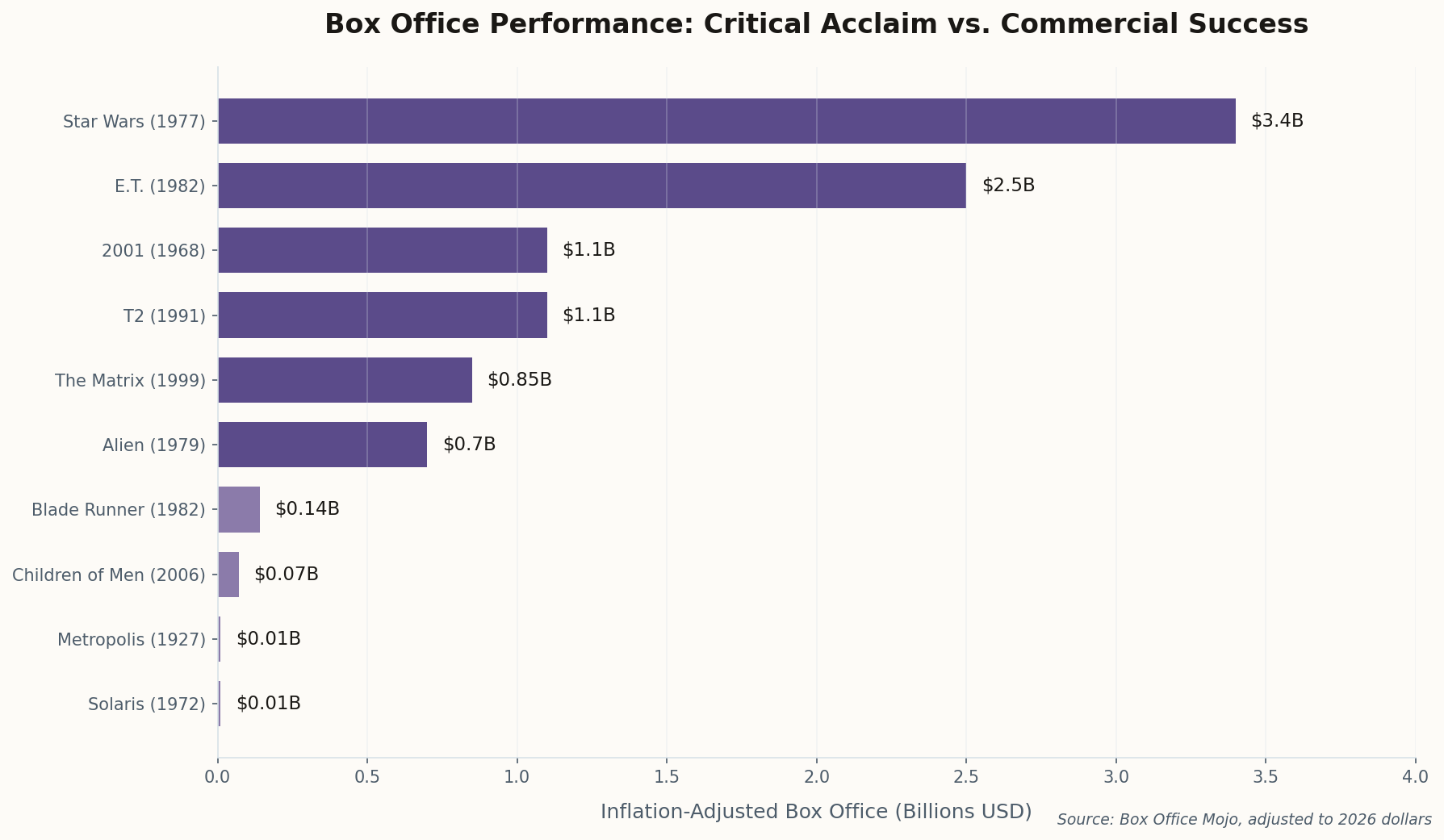

The numbers tell part of the story: five Grammy Awards for Best Comedy Album, the first Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize, and films that grossed over $3.5 billion adjusted for inflation. In 1980, he became the first Black actor to earn $1 million for a single film (Stir Crazy). His 1983 Columbia Pictures contract was worth $40 million—about $120 million today.

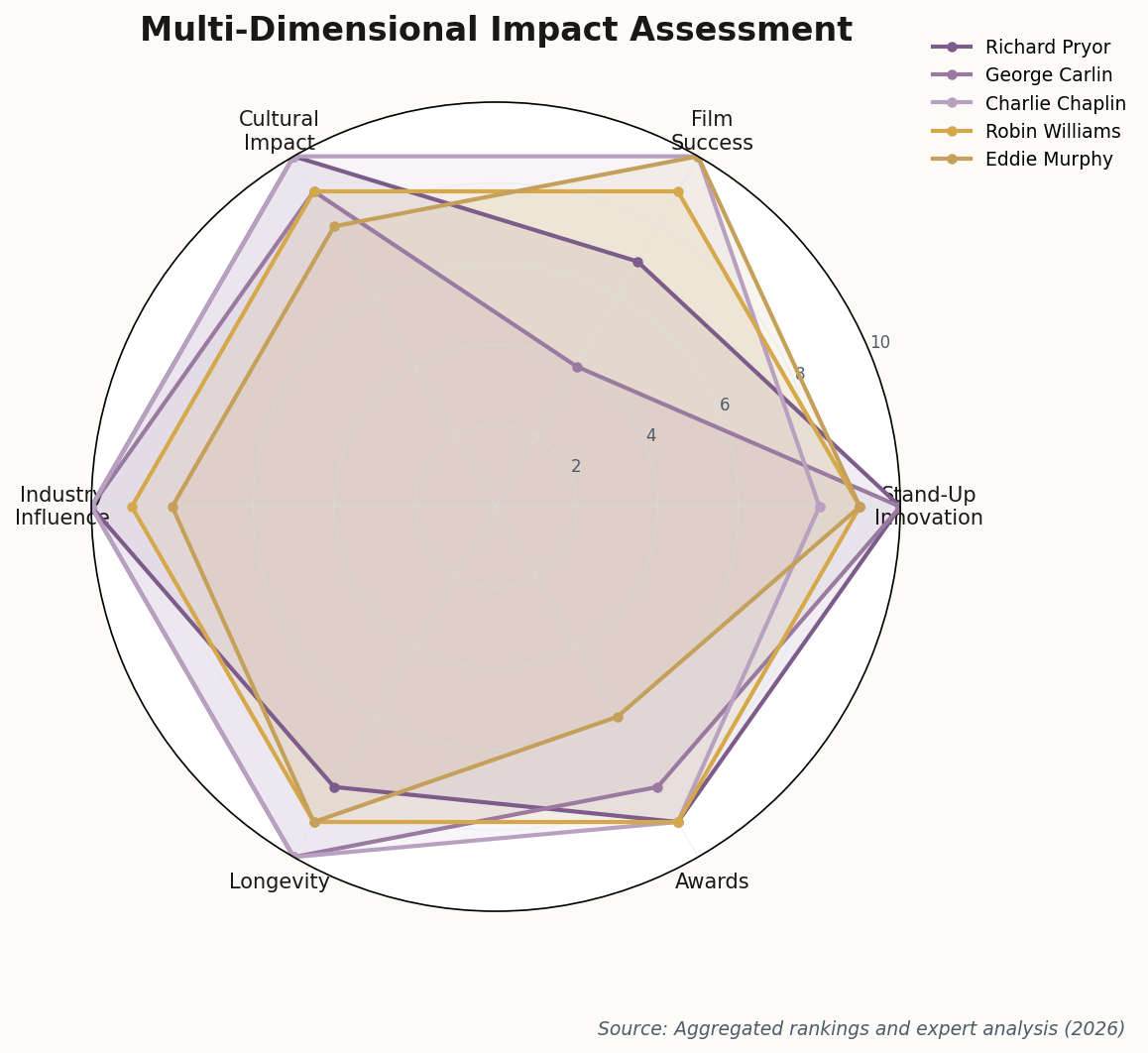

The Pryor Effect: Eddie Murphy, Chris Rock, Dave Chappelle—every Black comedian who followed walks a path Pryor macheted through the jungle. When Comedy Central ranked the 100 greatest stand-ups of all time in 2004, Pryor was #1. Not because he told the best jokes, but because he redefined what jokes could be.

His legacy isn't just influence—it's permission. Permission to be honest about pain. Permission to find humor in trauma. Permission to make the audience love you for your flaws, not despite them.