The Etymology of Empathy: What "House" vs. "Home" Actually Means

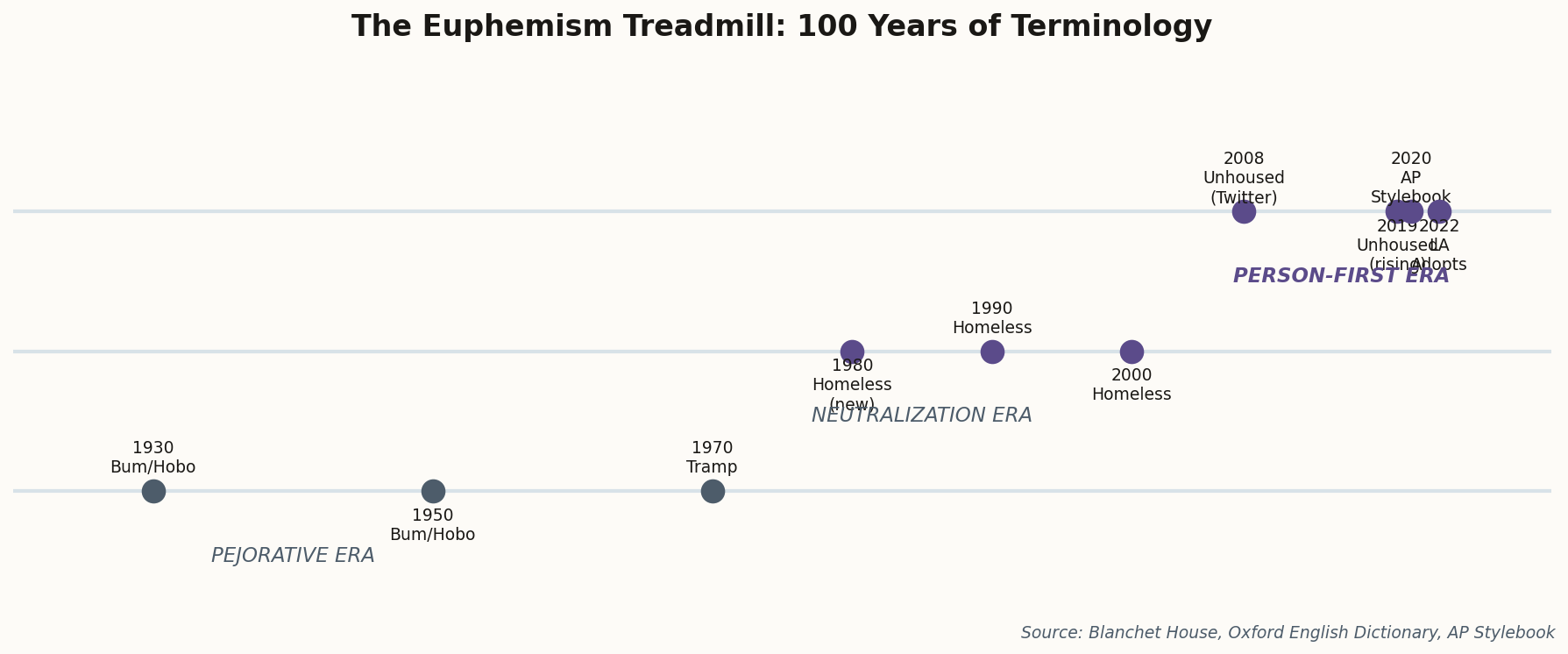

The shift from "homeless" to "unhoused" didn't happen in a Twitter boardroom or a city council chamber. It emerged from social service providers in Seattle during the 2000s who noticed something linguistically interesting: "home" and "house" aren't synonyms, and the distinction matters.

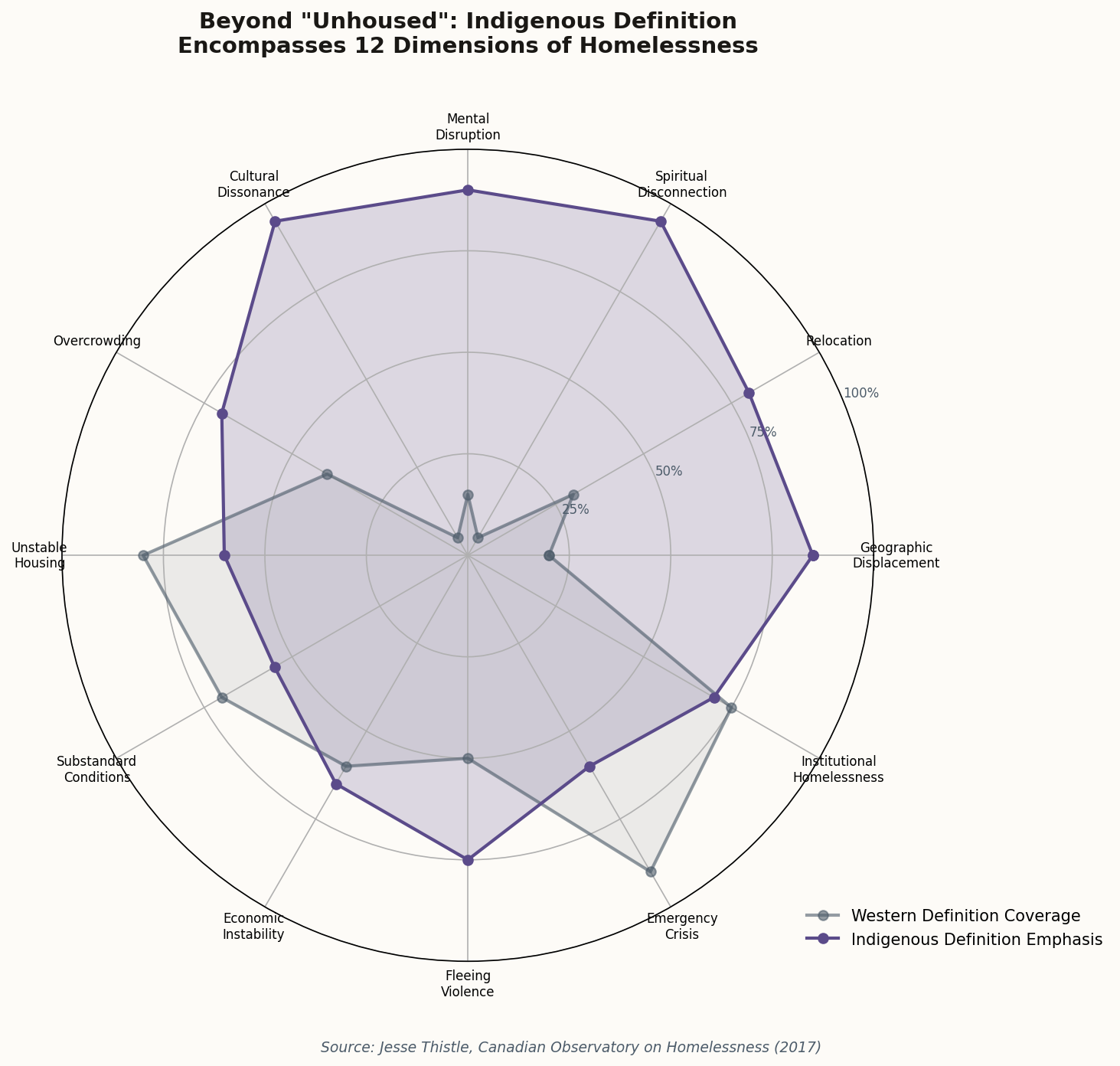

A peer-reviewed analysis in Cambridge's Modern American History traces the semantic shift. The argument goes like this: a person sleeping in a tent in their city of 20 years might be "unhoused" but not "homeless"—they have a community, a sense of place, roots. The term emphasizes that what's missing is a structure, not belonging.

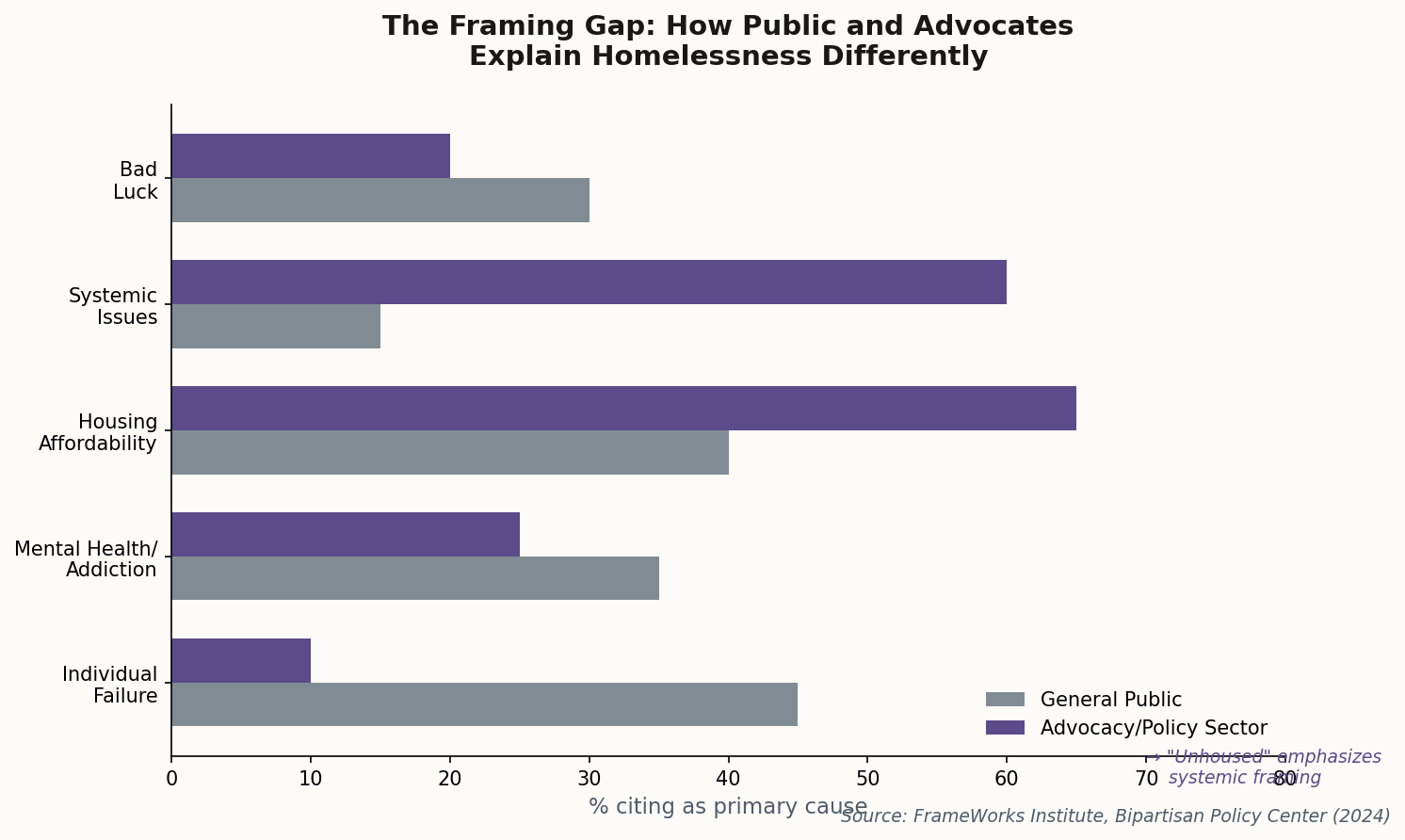

But here's where the academic analysis gets uncomfortable for advocates: the author argues that framing homelessness as purely a housing problem misses the deeper issue. "The term stressed the structural vulnerability of cities such that cities produced homelessness, and it is cities that needed to be fixed," the paper notes. Yet housing alone won't solve what is fundamentally a community development crisis for the extremely poor. The word change may have shifted blame—from individuals to systems—while still missing the actual target.