The DOJ Just Charged Protesters Under the KKK Act

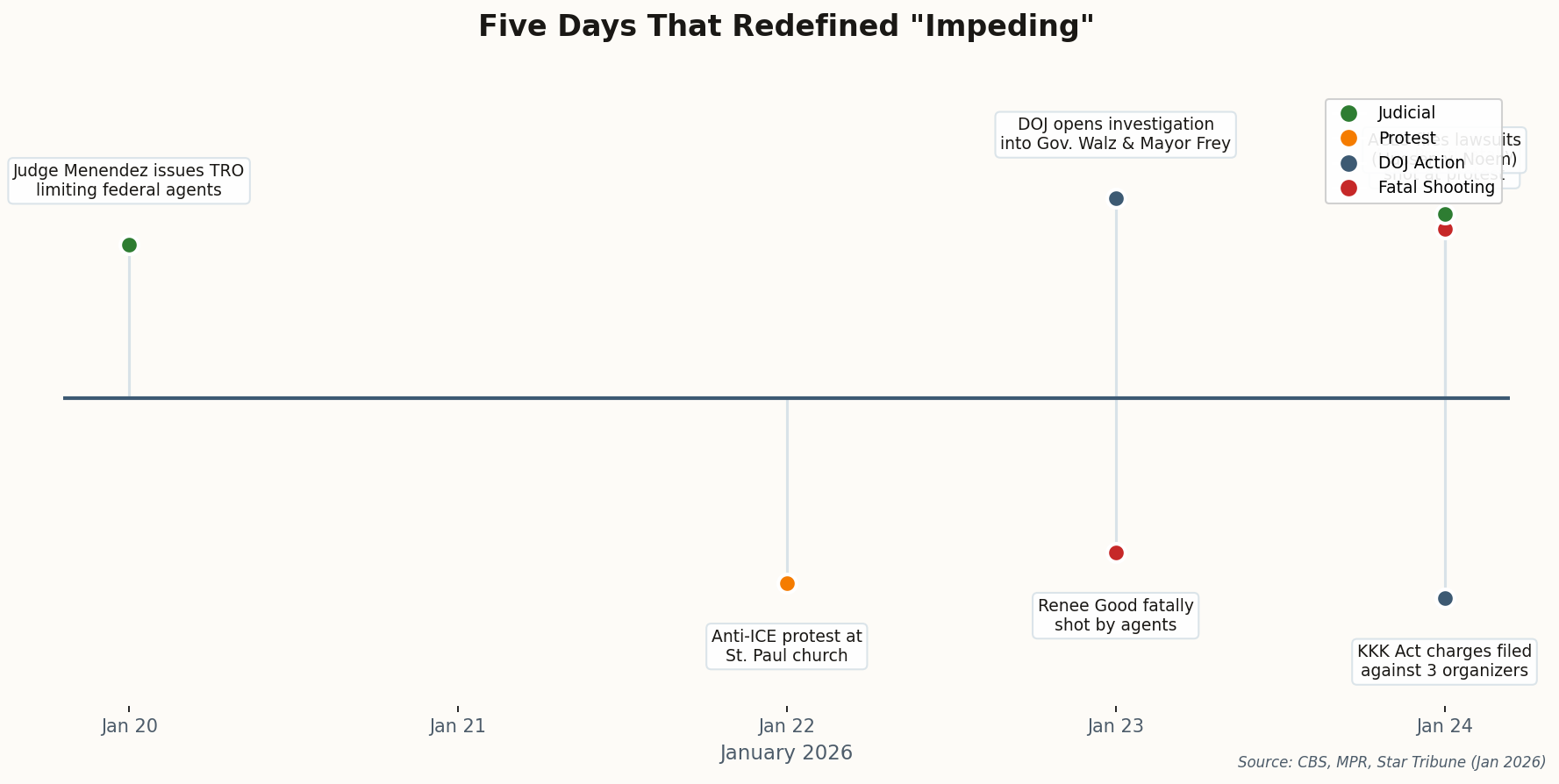

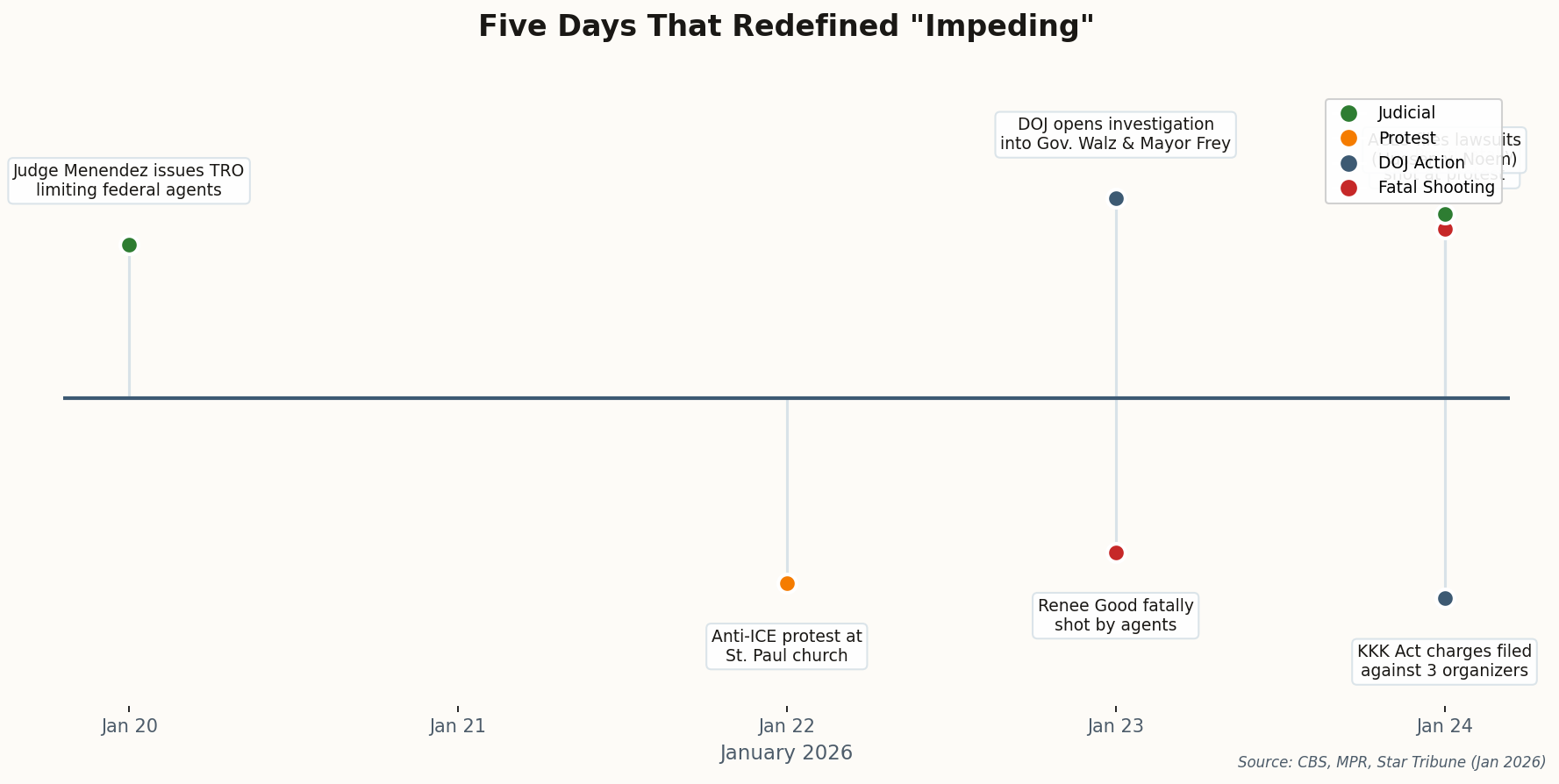

Here's what happened: Three protest organizers—Chauntyll Allen, Nekima Levy Armstrong, and William Kelly—entered a St. Paul church during an anti-ICE demonstration on January 22nd. They disrupted the service. In any other era, this would be trespassing or disorderly conduct—misdemeanors handled by the county.

Instead, the Department of Justice charged them with felony conspiracy under Section 241 of the Enforcement Act of 1871. You might know it better as the Ku Klux Klan Act—a statute created 155 years ago to prosecute nightriders terrorizing freedmen in the Reconstruction South.

Two organizers also face charges under the FACE Act (Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances) for "interfering with religious worship." This law was written to protect abortion clinics from blockades. Now it's being used against protesters at a church they entered voluntarily.

"We are seeing a federal civil rights statute designed to prevent terrorization... being used against protesters." — Jane Kirtley, University of Minnesota Law

The legal innovation here matters: the DOJ has federalized what would normally be a state offense. That's not about getting harsher sentences—it's about sending a message. Disrupt a federal operation, and you're not facing the local DA anymore. You're facing the full weight of federal prosecutors who can charge you under laws that predate the light bulb.

Two Protesters Dead. The Government Says They "Impeded."

Alex Jeffrey Pretti is dead. Federal agents shot him during a protest against immigration enforcement in Minneapolis on January 24th. The city confirmed a second death: Renee Good, shot the previous day during a related demonstration.

The official response was immediate and framed in legal terms. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem alleged that protesters "impeded and assaulted" officers, citing an incident where an officer's finger was allegedly bitten off. Attorney General Pam Bondi promised charges: "Protesters obstructed and assaulted law enforcement officers... charges will be filed."

The word "impeded" is doing heavy lifting here. It's the bridge between "they were in our way" and "we were justified in using lethal force." When the government claims someone impeded federal officers, it invokes a specific legal framework—18 U.S.C. § 111—that criminalizes "forcibly" assaulting, resisting, opposing, or impeding federal officers.

The question no one has answered yet: What, exactly, did Pretti and Good do that constituted "impeding"? Were they blocking a vehicle? Refusing to disperse? Simply being present? The legal definition matters because it determines whether lethal force was justified self-defense—or something else entirely.

Now the DOJ Is Investigating Whether State Officials "Impeded" ICE

The definition of "impeding" is expanding. The DOJ has opened an investigation into Minnesota Governor Tim Walz and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey—not for physically blocking anything, but for their words and policies.

Grand jury subpoenas have been issued to the Mayor's office and Hennepin County. The investigation centers on whether their public statements about immigration enforcement—and Minneapolis's sanctuary policies—constitute "impeding" federal law enforcement.

This is new territory. Previously, "impeding" meant physical obstruction: standing in a doorway, blocking a vehicle, refusing to move when ordered. Now the DOJ is testing whether administrative decisions and political speech can qualify. If a governor tells residents they don't have to cooperate with ICE, is that "impeding"? If a mayor tweets support for protesters, is that "conspiracy"?

The federalism implications are profound. Sanctuary policies have been litigated for years on Tenth Amendment grounds—states can't be commandeered to enforce federal law. But the DOJ isn't arguing Minneapolis must help; they're arguing Minneapolis can't hinder. The line between "declining to assist" and "actively impeding" is about to be tested in court.

A Judge Tried to Define the Line. The DOJ Rejected It.

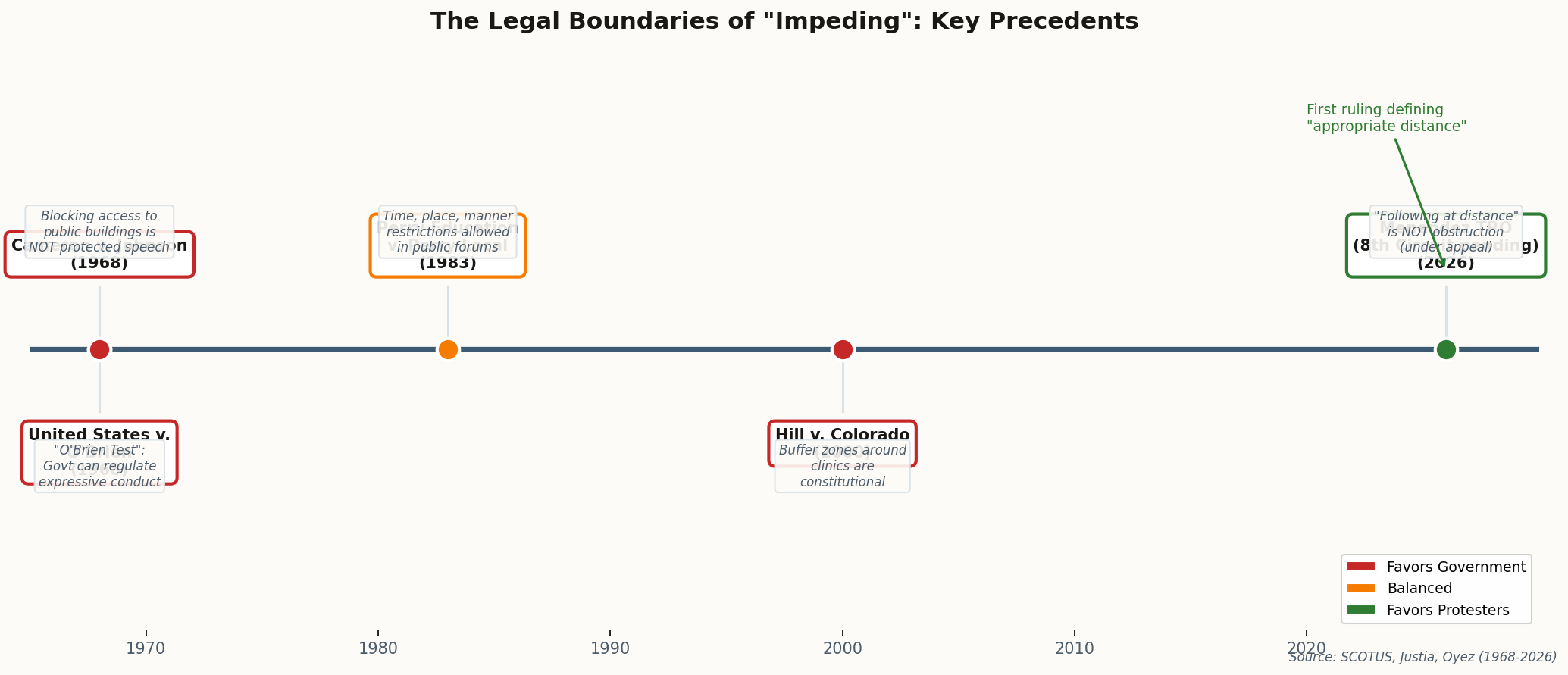

On January 20th, U.S. District Judge Katherine Menendez did something unusual: she issued a temporary restraining order that attempted to judicially define where "observation" ends and "obstruction" begins.

Her ruling stated: "Safely following agents at an appropriate distance does not, by itself, create reasonable suspicion to justify a vehicle stop." She barred federal agents from arresting peaceful protesters or using non-lethal munitions without probable cause.

The DOJ's response was immediate: appeal to the 8th Circuit. Their argument? This TRO "dangerously restricted law enforcement operations" and amounted to judicial micromanagement of field tactics. They want the restraining order lifted and any judicially-imposed definition of "impeding" thrown out.

"Safely following agents at an appropriate distance does not, by itself, create reasonable suspicion to justify a vehicle stop." — Judge Katherine Menendez

The appeal is telling. Judge Menendez tried to give protesters a bright line: stay this far back, don't physically interfere, and you're not "impeding." The government doesn't want that bright line. A vague standard means more prosecutorial discretion. It means the definition of "impeding" can expand to fit whatever the situation requires.

What "Impeding" Actually Means Under Federal Law

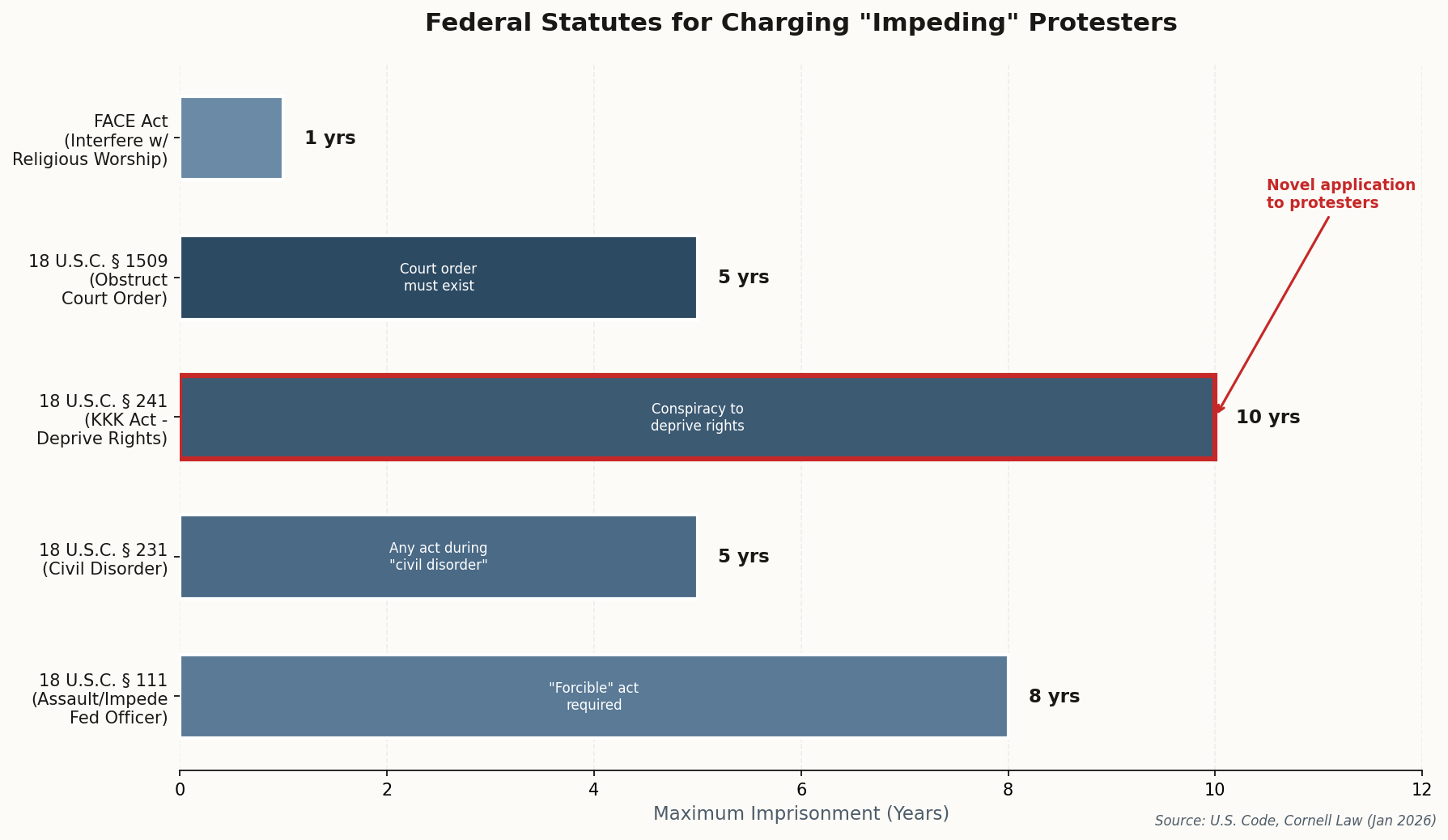

Three federal statutes matter here, and they're not interchangeable.

18 U.S.C. § 111 criminalizes "forcibly" assaulting, resisting, opposing, impeding, intimidating, or interfering with federal officers. The key word is "forcible"—mere passive refusal to move may not always qualify. But courts interpret "force" broadly. Struggling against handcuffs counts. Pulling away from an officer counts. The threshold is lower than you'd think.

18 U.S.C. § 231 (Civil Disorders) is broader and more dangerous for protesters. It makes it a felony to commit any act to obstruct, impede, or interfere with law enforcement during a "civil disorder"—defined as any public disturbance involving three or more people. You don't need to touch an officer. Any act that "obstructs" during a disorder qualifies.

18 U.S.C. § 241 (the KKK Act) prohibits conspiracy to "injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate" any person in the exercise of their civil rights. It was written to prosecute Klansmen who terrorized Black voters. Now it's being applied to protesters who disrupted a church service—the theory being that they conspired to deprive congregants of their right to worship.

Why "I Was Protesting" Isn't a Defense

The legal foundation was laid in 1968—the same year MLK was assassinated and cities burned. Two Supreme Court cases that year established boundaries that still govern today.

Cameron v. Johnson (1968) upheld a Mississippi statute prohibiting "picketing or mass demonstrations in such a manner as to obstruct or unreasonably interfere with free ingress or egress to and from any public premises." The Court ruled that while picketing is expressive conduct, blocking access to courthouses and public buildings is not protected speech.

United States v. O'Brien (1968) created the test that still governs. David O'Brien burned his draft card as symbolic protest. The Supreme Court convicted him anyway, establishing that government can regulate expressive conduct if: (1) it's within constitutional power, (2) it furthers an important government interest, (3) that interest is unrelated to suppressing speech, and (4) the restriction is no greater than necessary.

"We cannot accept the view that an apparently limitless variety of conduct can be labeled 'speech' whenever the person engaging in the conduct intends thereby to express an idea." — Chief Justice Earl Warren, O'Brien

This is why "I was protesting" doesn't work. If the government can show its obstruction laws are about ensuring operational efficiency (not silencing viewpoints), the conviction stands even if the conduct was politically motivated. The law doesn't care why you blocked the entrance. It only cares that you did.