The CBO Delivers Its Verdict: Immigration Is a Net Fiscal Positive

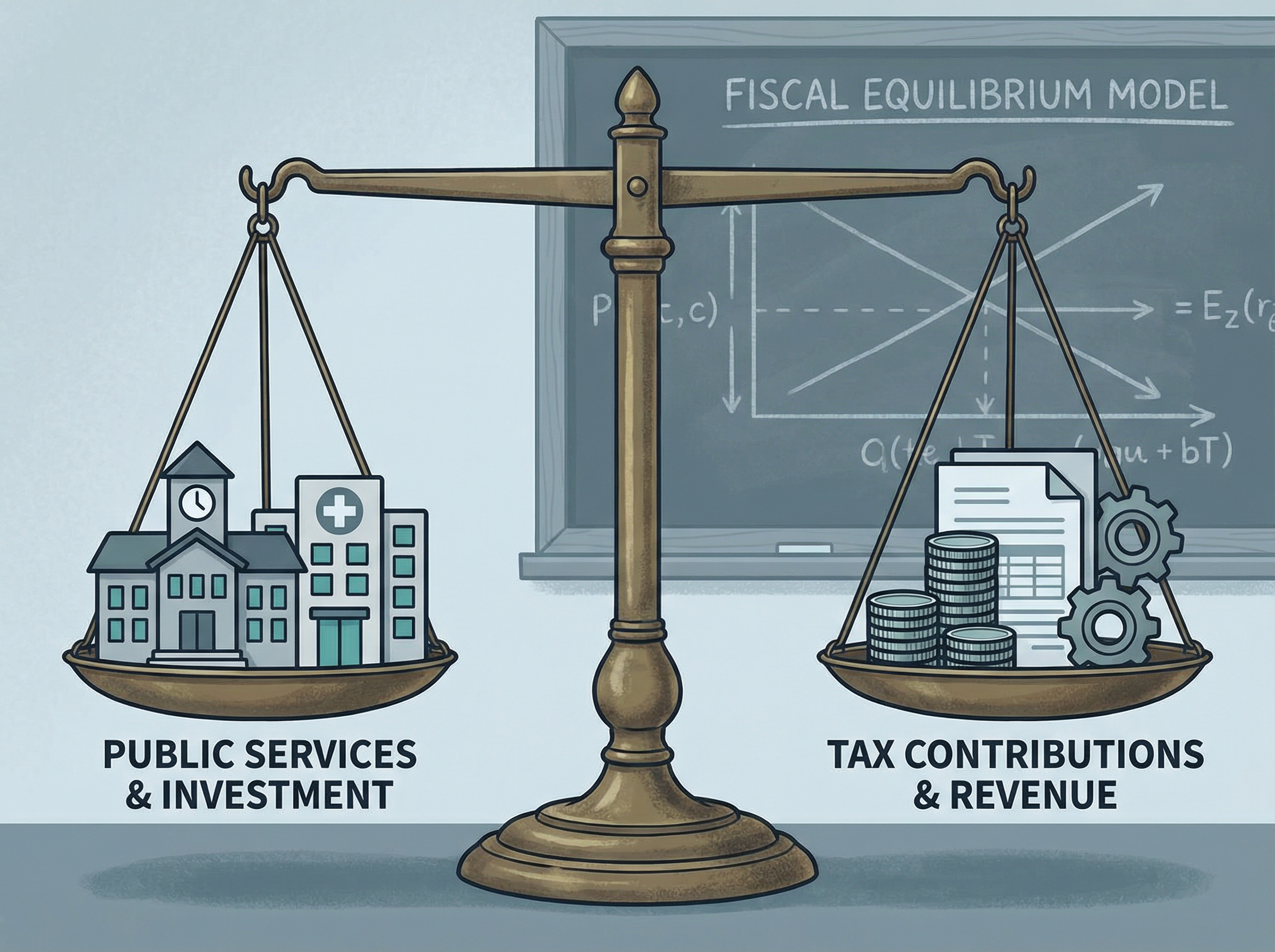

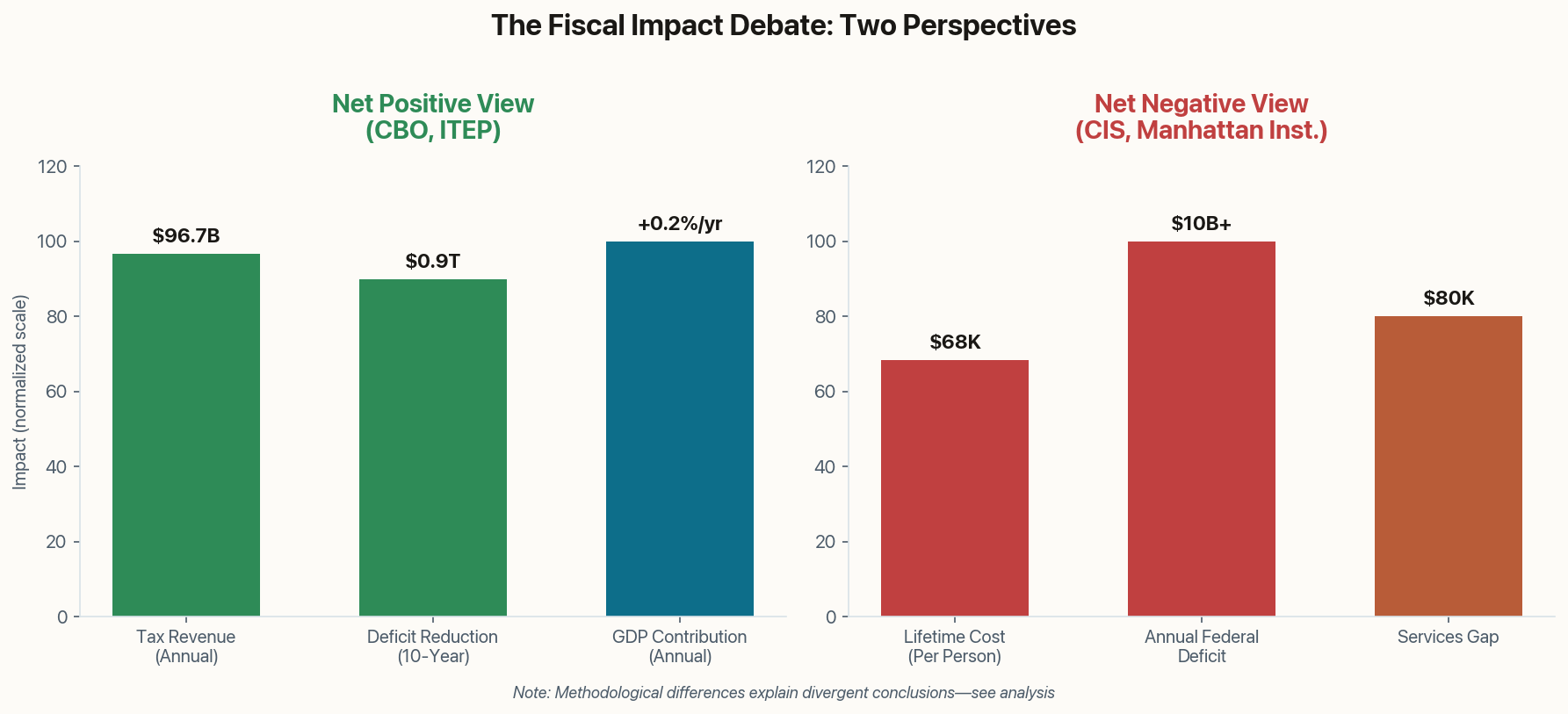

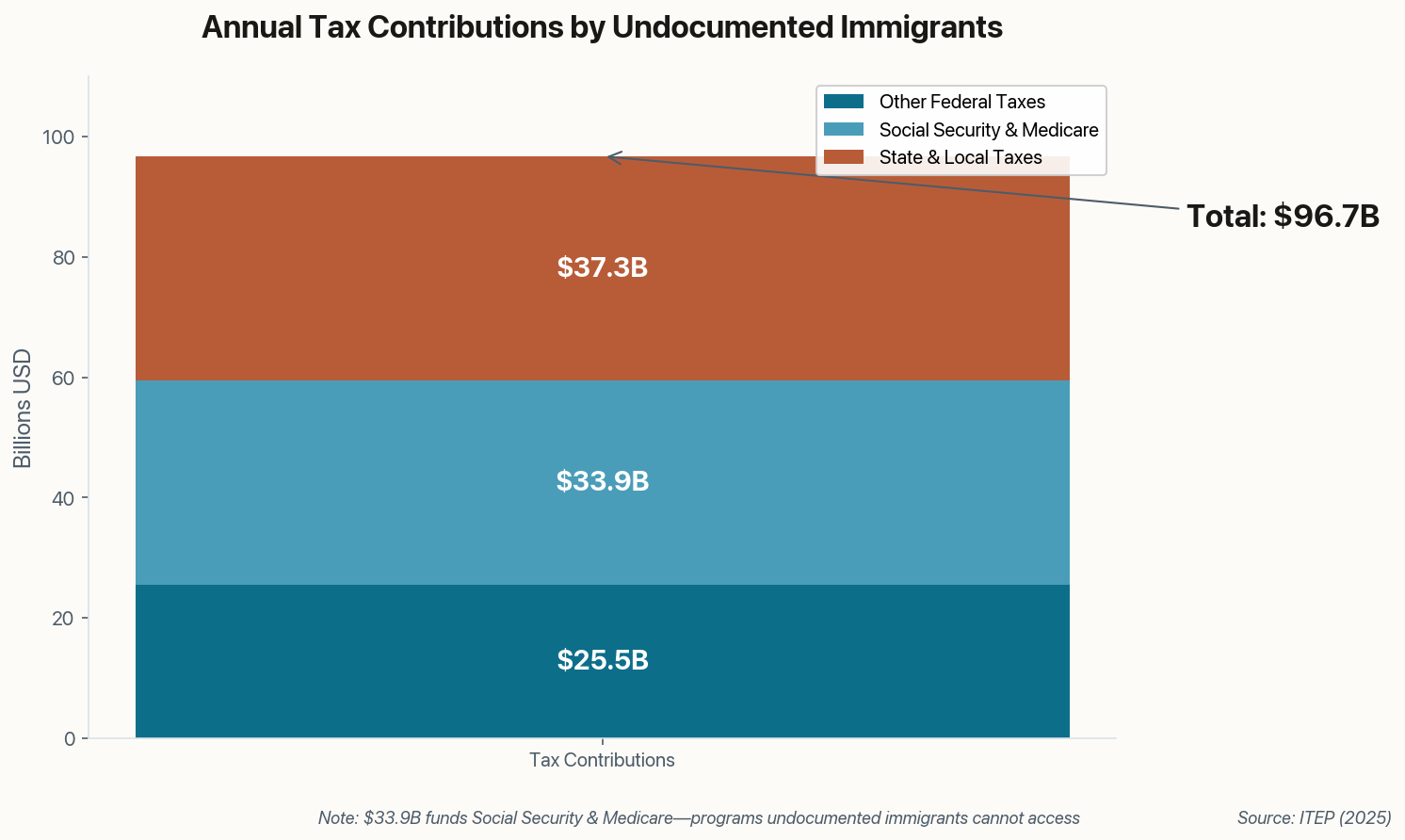

When the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office releases projections, policymakers on both sides typically stop arguing and start reading. The CBO's latest 10-year economic outlook contains a finding that should reframe the entire immigration debate: net immigration—including undocumented arrivals—will reduce the federal deficit by $0.9 trillion over the next decade.

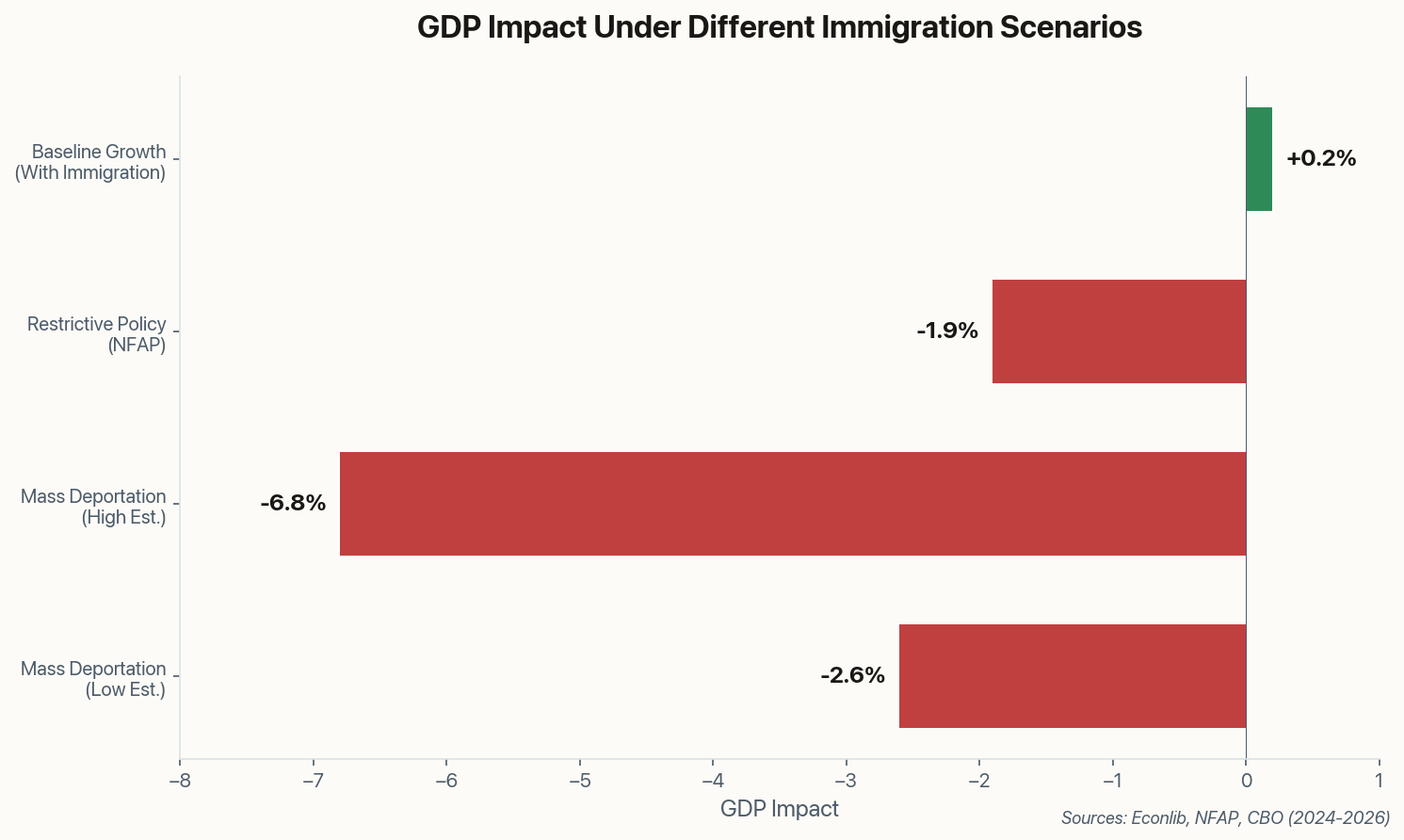

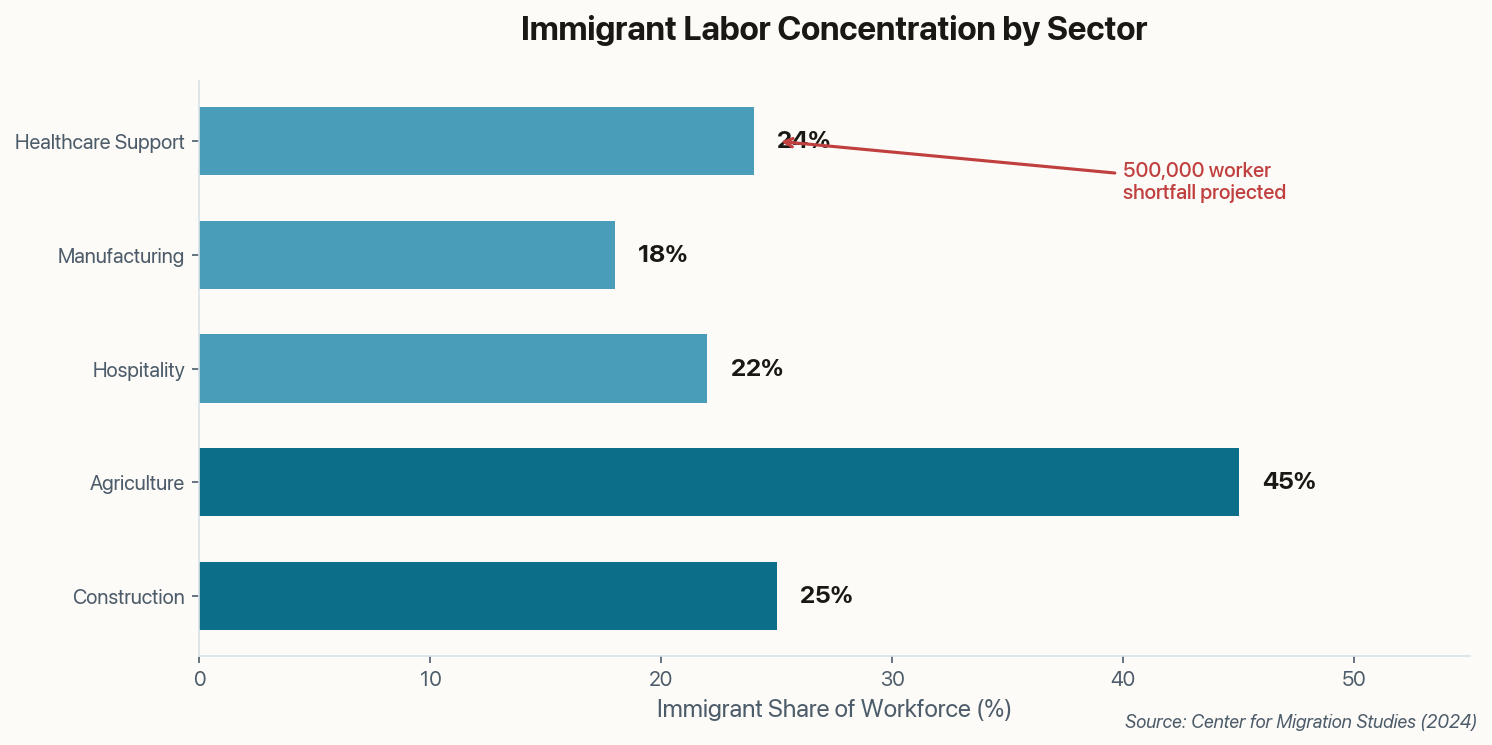

The mechanism is straightforward economics. A larger labor force means higher economic output, which generates more tax revenue. The CBO projects immigration will add approximately 0.2 percentage points annually to real GDP growth—modest in any single year, but compounding into real money over a decade. By 2030, immigration will account for all U.S. population growth as native birth rates continue their decline.

Key finding: "The labor force is projected to be larger than it would be without that immigration... resulting in higher economic output and additional tax revenue."

This isn't ideological framing—it's the baseline projection America's budget planners are using. Any policy that significantly reduces immigration isn't just a cultural choice; it's a fiscal decision with a $900 billion price tag.