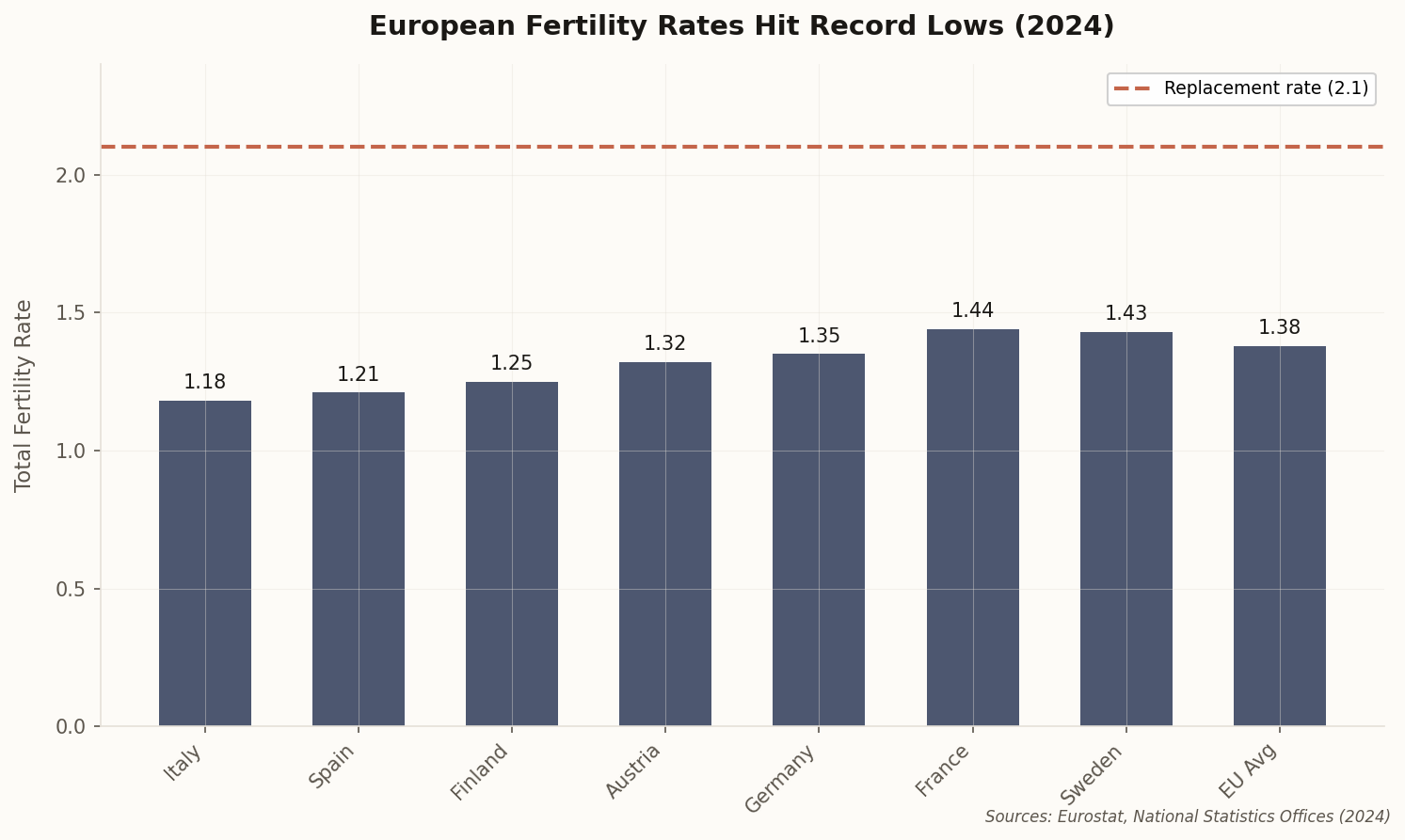

Europe's Fertility Collapse Hits New Lows

The numbers don't lie, and they're brutal. Italy recorded a total fertility rate of just 1.18 in 2024—for every 1,000 people, only six babies were born while eleven died. Finland hit 1.25, its lowest since recordkeeping began in the late 19th century. Germany dropped to 1.35, the worst since 1994. Even Sweden, long Europe's fertility poster child, fell to a record-low 1.43.

The replacement rate—the magic 2.1 children per woman needed to maintain population without immigration—hasn't been seen anywhere in Europe for decades. Monaco, with its 39,000 residents, is the sole exception, and that's a statistical quirk.

What's striking isn't just the decline—it's the acceleration. These aren't gradual slides. Country after country is reporting 2024 as their worst year ever for births. The demographic math is unforgiving: each generation is now arriving one-third smaller than its parents. There's no policy intervention that reverses this in the next decade. The 2035 population structure is already determined by who was born—or wasn't—in 2010.