The War's "Cause" Keeps Shifting—Even During the War Itself

Here's a question most textbooks dodge: did the war that ended in 1918 have the same "cause" as the one that started in 1914? A new wave of independent video essays—part of a broader shift toward high-quality historiography on YouTube—argues convincingly that it did not.

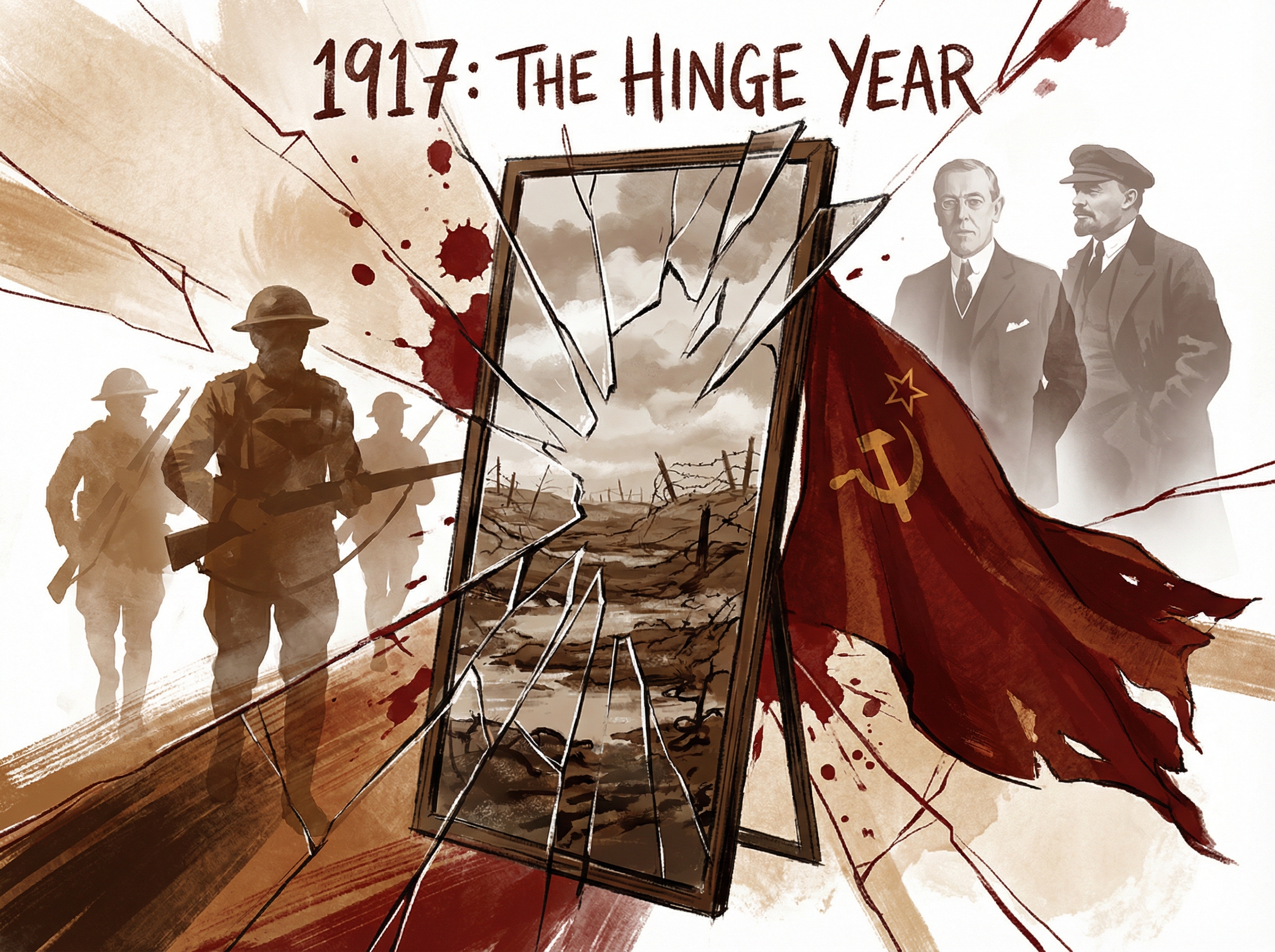

The documentary 1917: Turning Point of WW1 makes the case that this single year fundamentally rewrote the war's meaning. Before 1917, the conflict was recognizable as a 19th-century imperial struggle: Habsburgs versus Romanovs, colonial rivalries, naval arms races. After 1917? Woodrow Wilson entered with his Fourteen Points and crusade for democracy. Lenin countered with world revolution. Suddenly the war became ideological—a template for the rest of the 20th century.

This matters because it suggests that asking "what caused WWI?" may be the wrong question. Perhaps the more honest framing is: which WWI? The one that generals started for reasons of honor and alliance obligations, or the one that ideologues finished for utopian dreams? Younger audiences, raised on video essays rather than cable documentaries, increasingly see causation as something that evolves during events—not a static moment frozen in the summer of 1914.