Central Bankers Are Using 1930s Trade Data to Model 2026

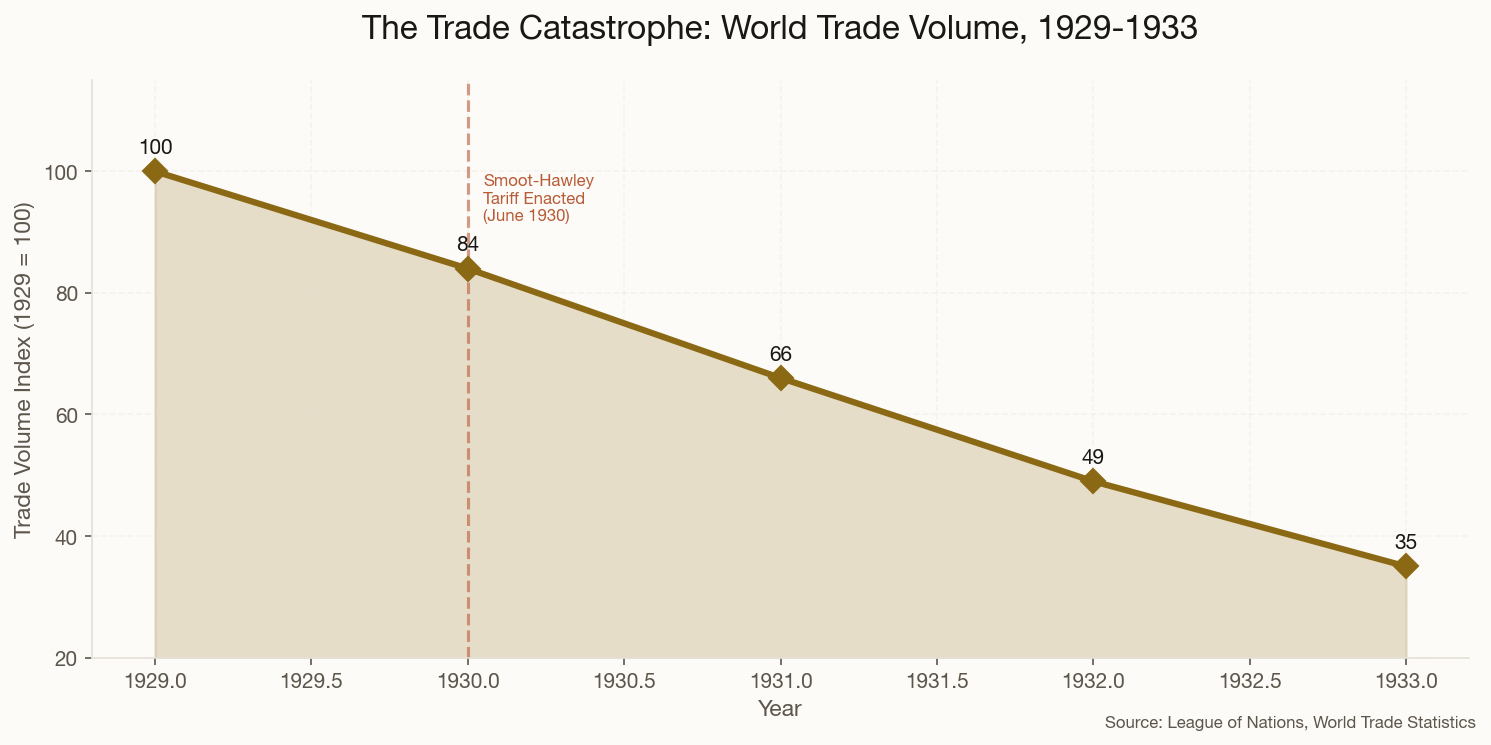

In a speech last week that should have received far more attention, Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee member Alan Taylor delivered a stark historical comparison. The 1930s, he argued, represented "the first era of deglobalisation"—a period when trade collapsed not because moving goods became harder, but because governments chose to make it so.

The parallel to 2025-2026 is intentional and uncomfortable. Taylor explicitly invoked "geoeconomic fragmentation"—the diplomatic term for the tariff escalations, sanctions regimes, and supply chain reshoring now reshaping the global economy. His thesis: these are "man-made, not technological" barriers, just as Smoot-Hawley and its retaliatory cascade were in 1930.

What makes this notable isn't the historical analogy itself—plenty of op-eds draw that line. It's that a sitting central banker is publicly using Depression-era trade data as an input to current monetary policy modeling. The message to markets: the institutional memory of the 1930s is no longer academic. It's operational.

The quote: "The Great Depression was the first era of deglobalisation... where trade levels fell significantly not due to cost, but policy."