The Face That Launched a Trillion Dollars—Now on a Dollar

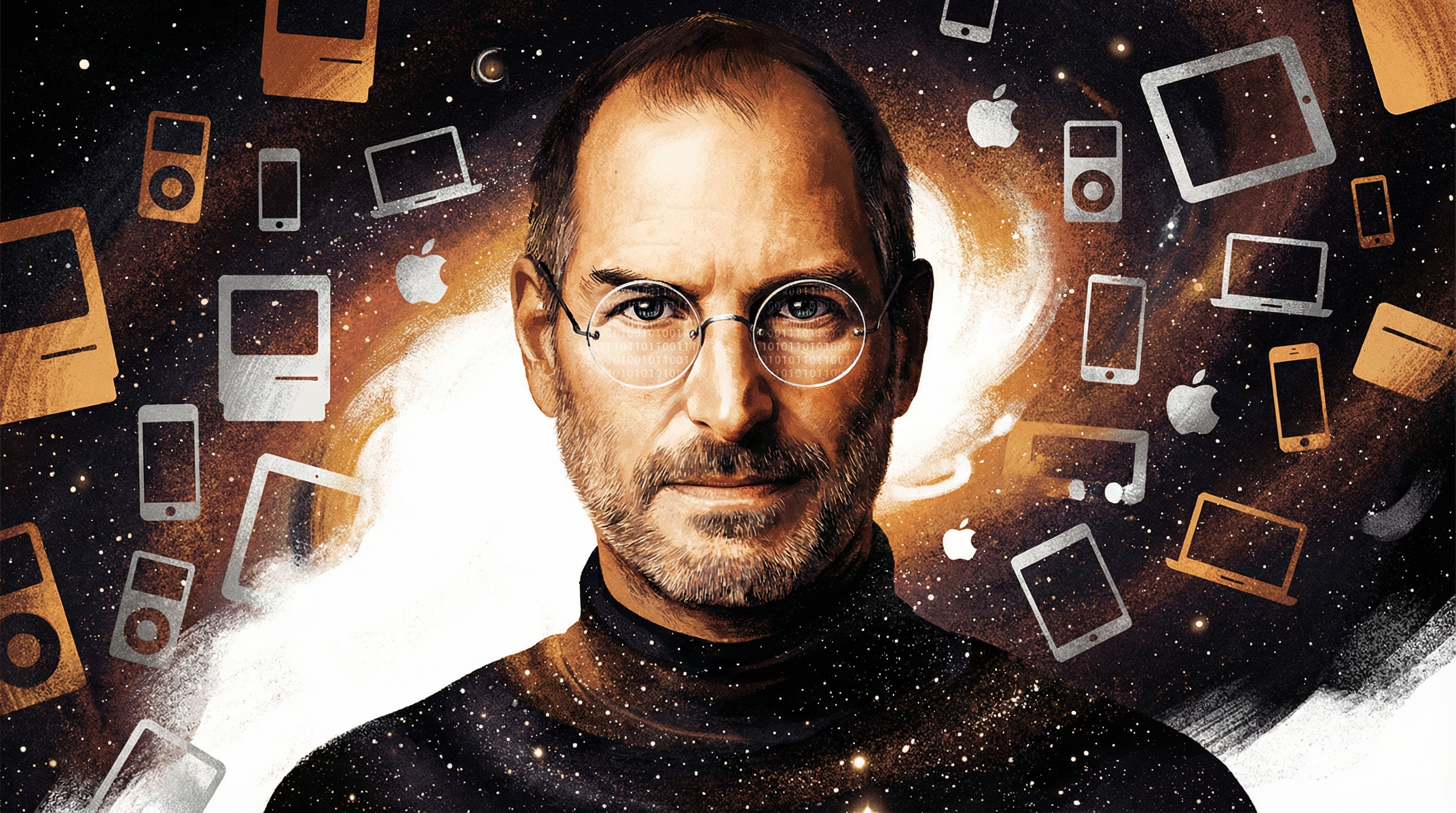

When the U.S. Mint announced Steve Jobs would appear on a $1 coin as part of the American Innovation series, the reaction was predictably split: canonization or commercialization? The coin features a young Jobs—turtleneck, round glasses, the whole mythology—with the inscription "Make Something Wonderful."

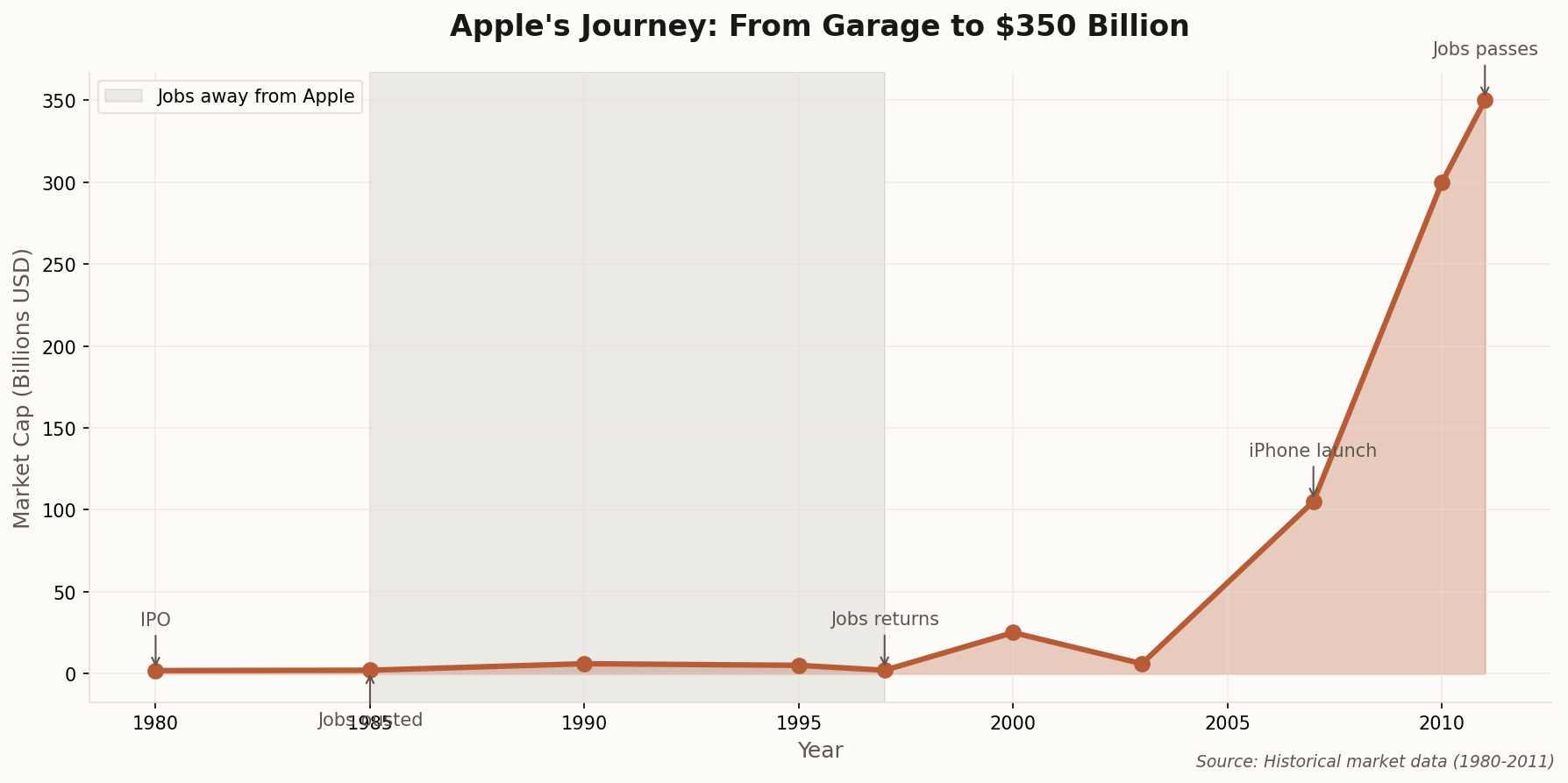

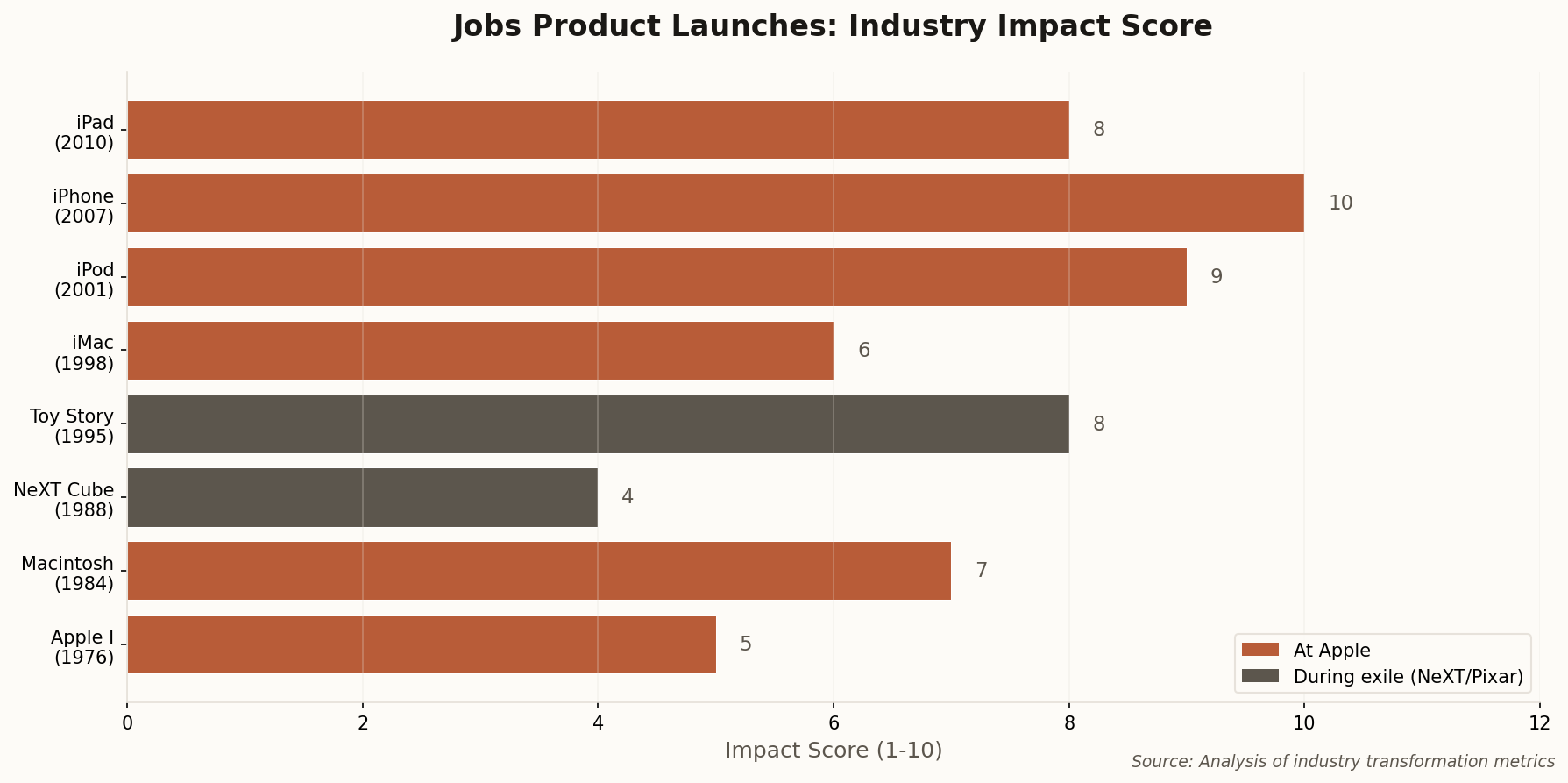

Here's what's remarkable: Jobs is the California representative for 2026, edging out everyone from Walt Disney to the founders of Google. That the Mint chose a Buddhist who dropped acid, abandoned his daughter, and famously didn't believe in philanthropy says something about how America measures greatness. We don't put saints on our money. We put people who changed things.

The deeper irony: Jobs spent his career eliminating cash. Apple Pay, the digital wallet that made credit cards feel quaint—that was his vision made manifest. Now his face will end up in tip jars and parking meters, a physical relic from a man who worshipped the digital future.

The "Make Something Wonderful" inscription comes from a posthumous collection of Jobs' writings and speeches, curated by his wife Laurene Powell Jobs and the Steve Jobs Archive. It's become the closest thing to an official motto for his legacy.