The Biography Everyone's Waiting For

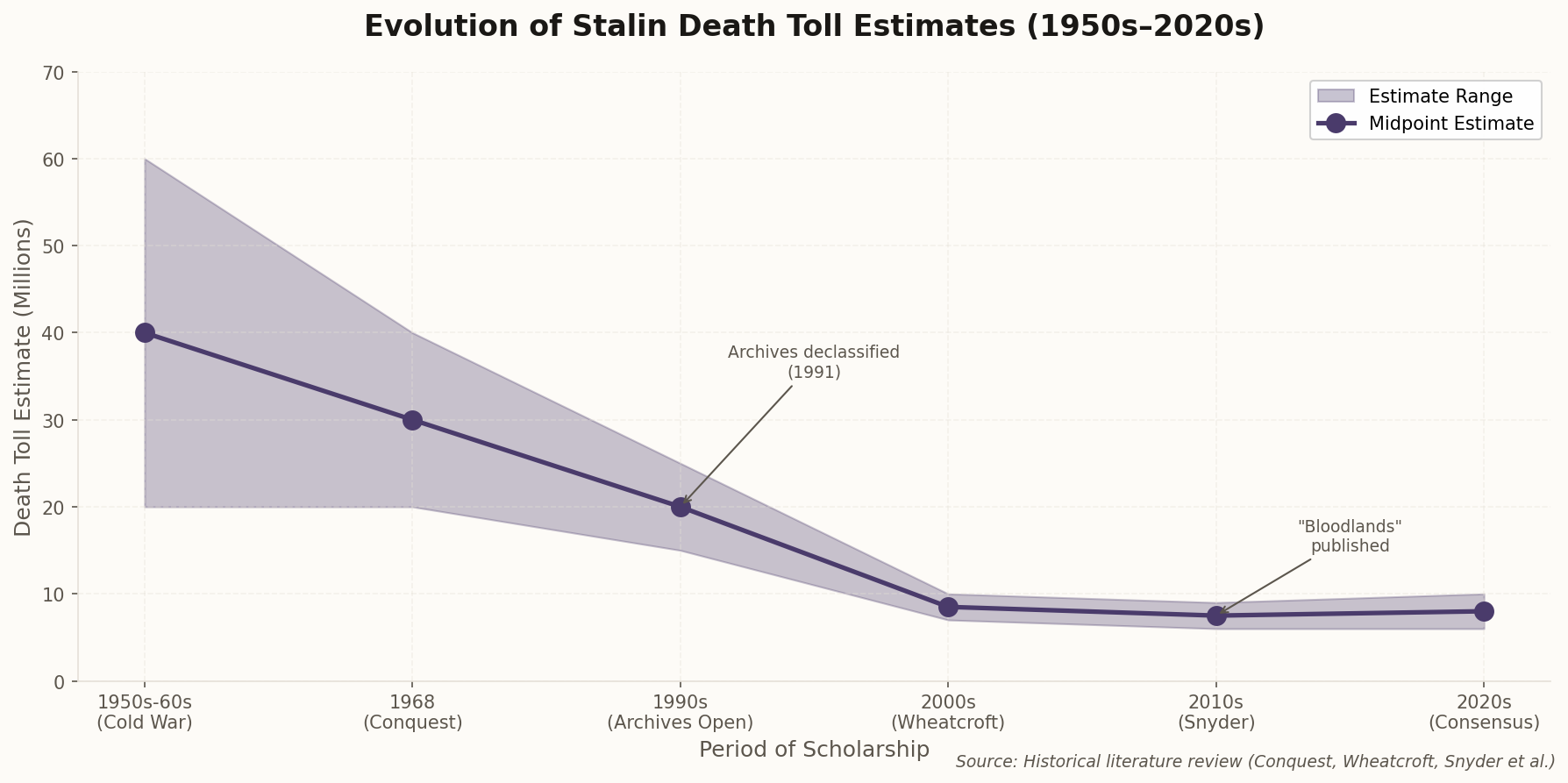

The historical community is holding its breath. Stephen Kotkin's third and final volume of his monumental Stalin biography—covering World War II through Stalin's death in 1953—is expected this year, and it will likely reset the entire conversation about Stalinist mortality.

Kotkin's previous two volumes established him as the definitive modern biographer of Stalin, combining exhaustive archival research with a readable narrative style that's rare in academic history. His interpretation is neither apologetic nor hysterical: Stalin was rational (to himself), geopolitically motivated, and intimately involved in the machinery of death. The terror wasn't madness—it was method.

What makes Volume III so anticipated is its scope. The war years and immediate postwar period saw some of Stalin's most consequential decisions: the deportations of entire ethnic groups, the treatment of returning POWs, the postwar purges. Kotkin's archival access has been unprecedented. His conclusions will be hard to ignore.

The working title remains speculative—"Totalitarian Superpower" has been floated—but whatever it's called, this book will likely become the new baseline for serious Stalin scholarship. Everyone else will have to respond to it.