Reddit's Pitmasters Draw Their Battle Lines

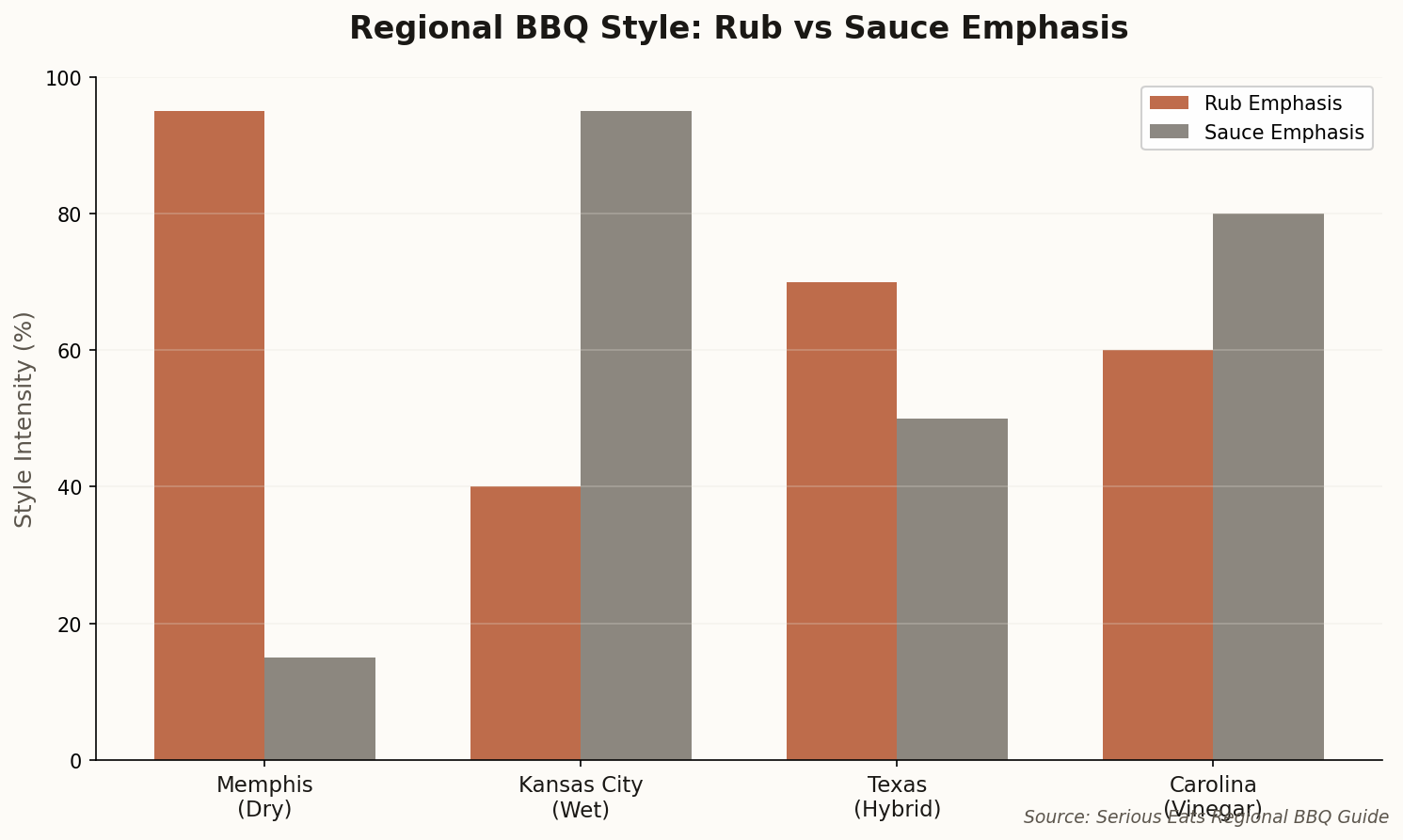

A particularly fiery thread erupted last week in r/smoking when a user posted their boneless short ribs finished with a "Smoke & Fire" dry rub and asked the eternal question: sauce or no sauce? The community's verdict was decisive, if divided.

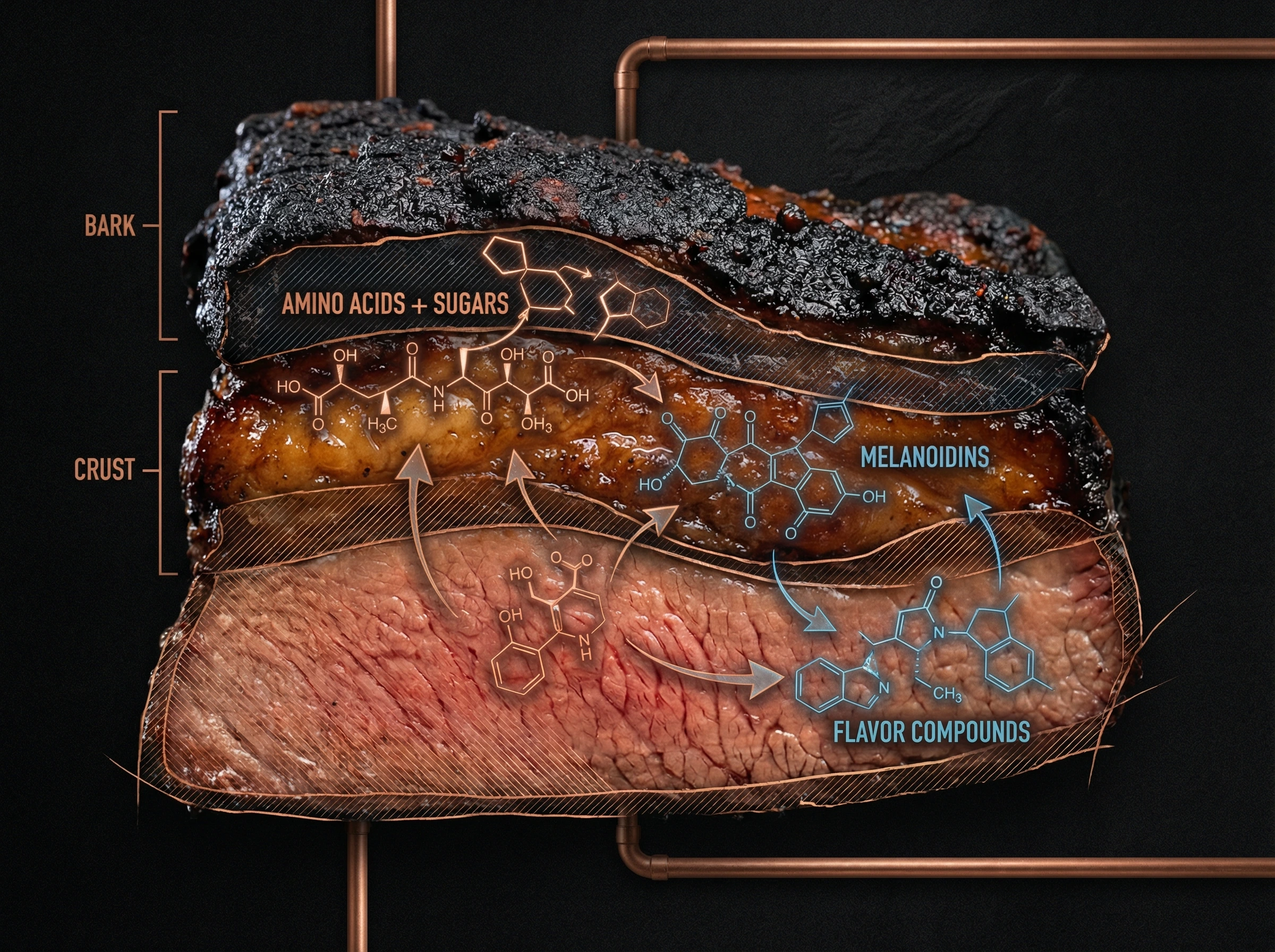

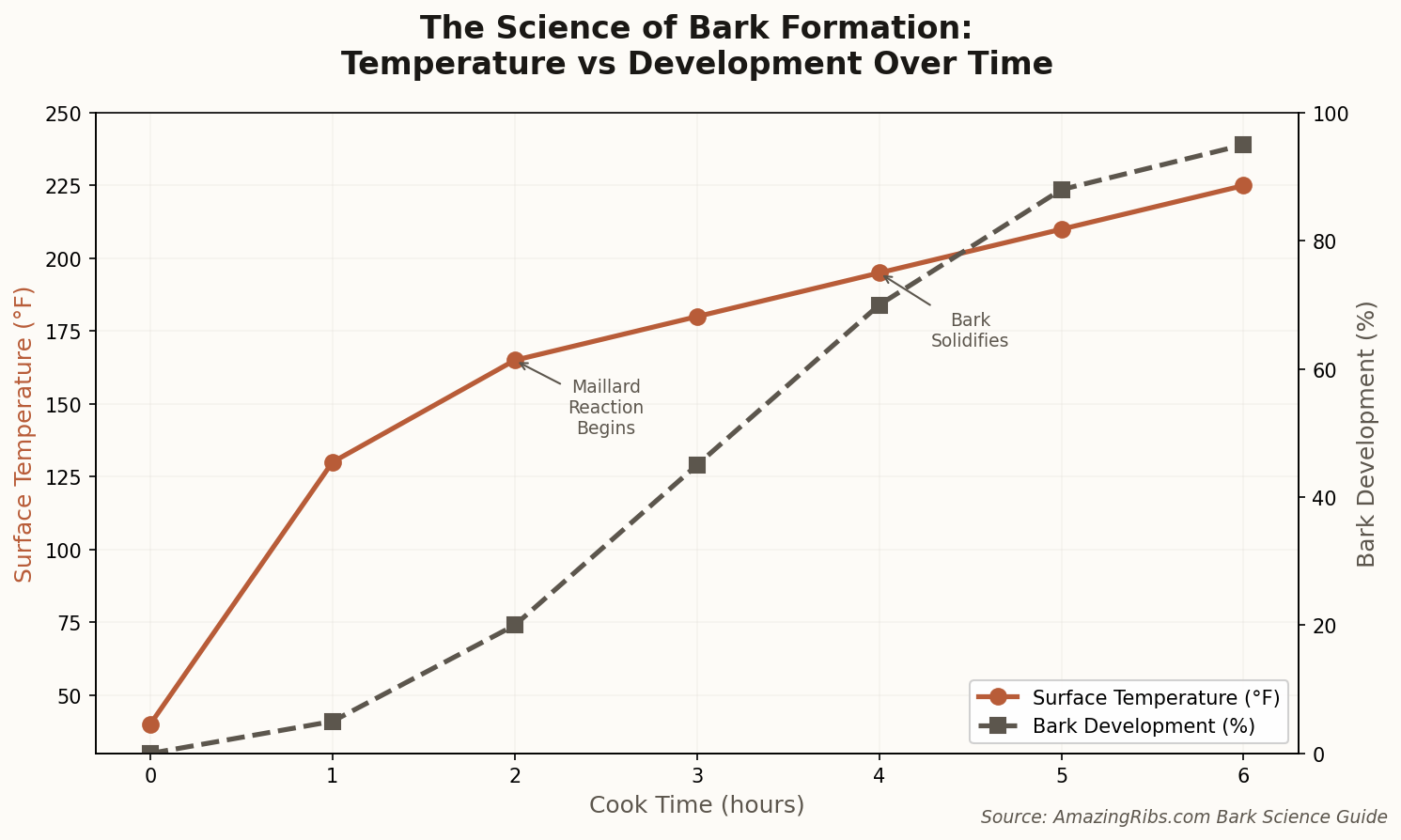

The dry-finish advocates dominated the conversation, arguing that bark texture represents the pinnacle of pitmaster craft. "Dry ribs can sometimes indicate undercooking," one user cautioned, "but a good bark requires that surface dehydration." The subtext was clear: sauce is a crutch for those who can't nail the smoke ring and crust on their own.

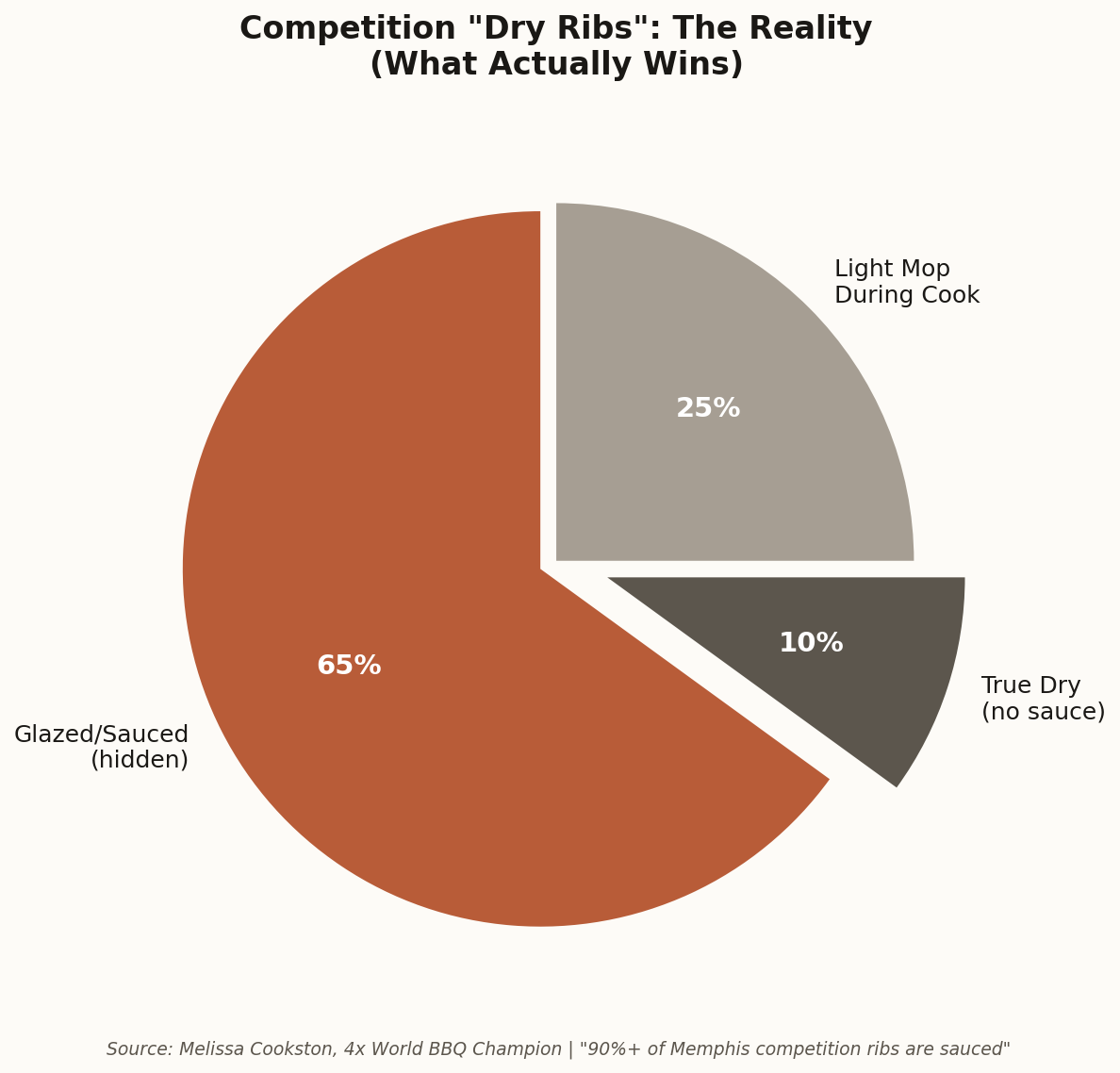

The wet camp fired back with accusations of culinary purism run amok. Their position: a perfectly sauced rib delivers a complexity of flavors—sweet, tangy, caramelized—that no amount of paprika and brown sugar can match. The thread's consensus? Serve sauce on the side and let the eater decide. A diplomatic solution, or a cop-out? That's the meta-debate.

The takeaway: Grassroots BBQ culture is increasingly favoring texture over sauciness. The bark is no longer optional—it's the standard by which ribs are judged.