From Blood Clot to Universal Ruler

The boy who would reshape the world was born clutching a blood clot in his fist. Around 1162, near the modern border of Mongolia and Siberia, a child named Temujin entered a world that seemed determined to kill him.

His father Yesugei, a minor tribal chief, was poisoned by rival Tatars when Temujin was just nine years old. What followed was betrayal at its most brutal: his own tribe abandoned the family, leaving a widow and her children to survive the harsh steppe winters alone. The message was clear: without a protector, you were nothing.

But Temujin refused to be nothing. Through a combination of strategic alliances (including his blood brotherhood with Jamukha, who would later become his rival) and an almost preternatural ability to inspire loyalty, he clawed his way up the brutal hierarchy of steppe politics.

The Meritocracy Revolution: Temujin broke with tradition by promoting men based on competence and loyalty rather than birth. This simple innovation would prove revolutionary, creating an army where a former slave could become a general.

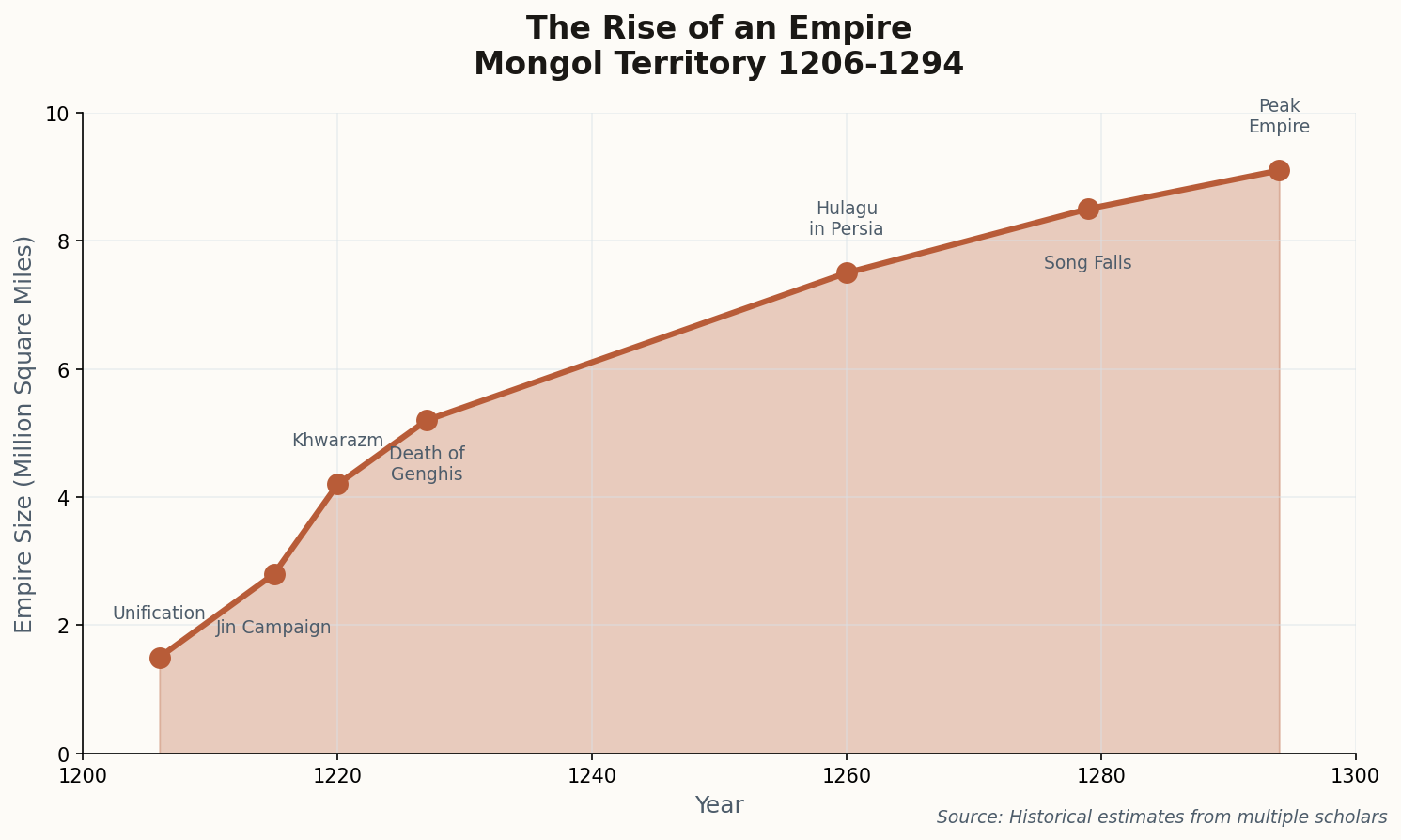

In 1206, at a kurultai (grand council) on the banks of the Onon River, the warring Mongol tribes proclaimed him "Genghis Khan," the Universal Ruler. He was approximately 44 years old, and he had only just begun.